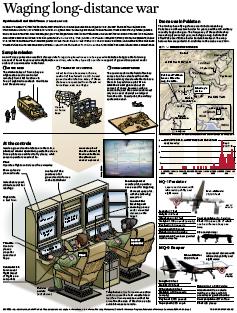

The Chicago Tribune has a good graphic on the US unmanned air campaign targeting the Taliban and al Qaeda in Pakistan.

Monday’s deadly airstrike in northwest Pakistan marks the latest example of US forces’ increasing reliance on unmanned aircraft, or drones, to target Al Qaeda and Taliban personnel in the region. These remotely-piloted planes, such as the Predator and the Reaper, play an important role in surveillance and targeting of enemy forces in Pakistan and have been used in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The planes are guided remotely from command centers in the US using technology that allows pilots on the other side of the world to control their actions, including firing missiles. These strikes have become controversial following incidents in which drone-fired missiles have killed non-combatants.

The graphic conveys a sense of the complexity behind running the remote war and provides a quick look at the two platforms – the Predator and its successor, the Reaper. The illustration also shows us that the remote air war isn’t likely to end any time soon. The US has averaged about six to seven strikes a month since August 2007 (with some peak and valley months) and there is no indication this will stop. In fact, the statistics suggest that the frequency of the strikes is, if anything, increasing.

The civilian casualties attributed to the drone strikes that have been reported by the Pakistanis and repeated uncritically by counterinsurgency experts such as David Killcullen and Andrew Exum in The New York Times are highly exaggerated and taken out of context.

Alexander Mayer and I took a look at the data behind the strikes, back on July 21. Sifting through the press reports, it became clear that the vast majority of those killed are Taliban and al Qaeda fighters.

The strikes have decidedly been effective. Since July 21, there have been seven more strikes in Pakistan, one of which killed former Pakistani Taliban leader Baitullah Mehsud and another that may have killed Mustafa al Jaziri, a member of al Qaeda’s military shura. The rest of the list is here. After looking at who has been killed, and taking into account the purpose of the campaign – to disrupt al Qaeda and the Taliban’s ability to strike in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and against the West and other allies, not just to headhunt al Qaeda leaders – it is tough to argue that the benefits have not outweighed the costs.

Are you a dedicated reader of FDD's Long War Journal? Has our research benefitted you or your team over the years? Support our independent reporting and analysis today by considering a one-time or monthly donation. Thanks for reading! You can make a tax-deductible donation here.