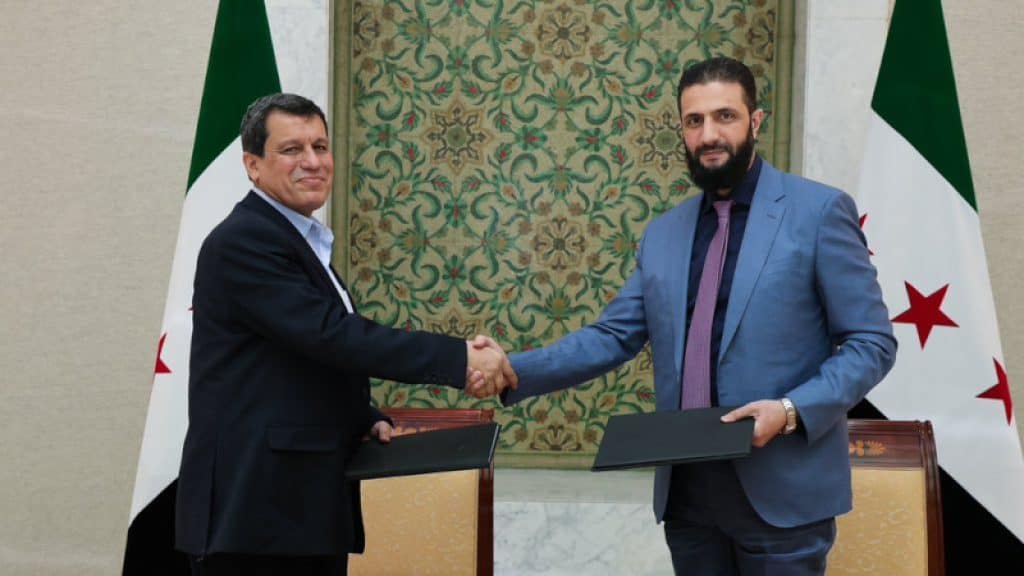

On March 10, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) signed an agreement with Syria’s interim government, integrating the SDF’s 100,000-strong, predominantly Kurdish force into the new Syrian military. This move is surprising, given the deep distrust Syria’s Kurds have toward the interim government led by Ahmed al Sharaa.

Sharaa, formerly the leader of Hayat Tahrir al Sham (HTS)—a previously Al Qaeda-affiliated group with historic ties to the Islamic State (IS)—was long perceived by the Kurds as a jihadist figure intent on dismantling Kurdish autonomy. Since 2015, the United States has directly partnered with the SDF to combat IS. However, after overthrowing dictator Bashar al Assad, Sharaa dissolved HTS and repositioned himself and former HTS elites as Syria’s new interim rulers. Seeking Western legitimacy, the new regime has promised inclusivity, hoping for the removal of international sanctions and terrorism designations on HTS leaders, including Sharaa himself.

Initially, the SDF remained cautious as Kurdish leaders doubted that a former jihadist could establish an inclusive government. Their concerns were reinforced by early post-Assad attacks on Kurdish areas by Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) militias and Turkish drone and artillery strikes targeting civilian infrastructure. Despite these hostilities, Sharaa called on the SDF to dissolve and integrate into the Syrian military—a demand the Kurds resisted until March 10.

The SDF’s calculated risk

Why did the SDF ultimately accept integration? The most plausible explanation is a security guarantee from Turkey. On February 27, Abdullah Ocalan, the imprisoned Kurdish leader, was permitted by Turkish authorities to issue a public statement calling for the disarmament and dissolution of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), an organization Ocalan established. The PKK, designated a terrorist organization by the US and Turkey, is the ideological parent of the SDF’s fighting forces.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been negotiating with Ocalan, likely to secure the Kurdish parliamentary votes needed to amend the constitution and extend his rule beyond the current term limit. In return, Ocalan may have demanded constitutional guarantees for Kurdish political and cultural rights, as well as assurances that Turkey would not attack the SDF.

A risky gamble

Some may see the agreement between the SDF and the new Syrian regime as a Faustian bargain. Given a potential US withdrawal from Syria, the SDF faces a stark reality: without American protection, it risks annihilation by the Turkish military. Integrating into the Syrian armed forces could provide the SDF a temporary buffer against Turkish aggression.

However, the nature of this integration remains uncertain. If Sharaa’s forces continue targeting minorities—such as the Alawite massacres on March 7—or if Kurds face renewed persecution, the SDF likely has contingency plans to withdraw from the agreement. For now, the deal reflects a pragmatic, albeit precarious, survival strategy in an unpredictable conflict.