The conflict that Hezbollah initiated against Israel on October 8, 2023, is now one year old. The group vowed to maintain this “support front” for its allies in the Gaza Strip to bleed Israeli morale and treasure through attrition until a premature ceasefire would allow “the Palestinian resistance in Gaza, and Hamas in particular, to emerge victorious.” But Hezbollah doesn’t understand Israel. It, therefore, misread the Israeli national mood on October 8, bogging itself down in a war of attrition that lasted far longer than the group expected or intended.

However, two things were predictable about this conflict from the outset: the first was that Hezbollah could not back down from attacking Israel in support of Gaza without looking weak and risking its own unraveling. The second was that this war of attrition, having exposed a Hezbollah threat to northern Israel not amenable to diplomatic resolution, would eventually and inevitably evolve into the Third Lebanon War.

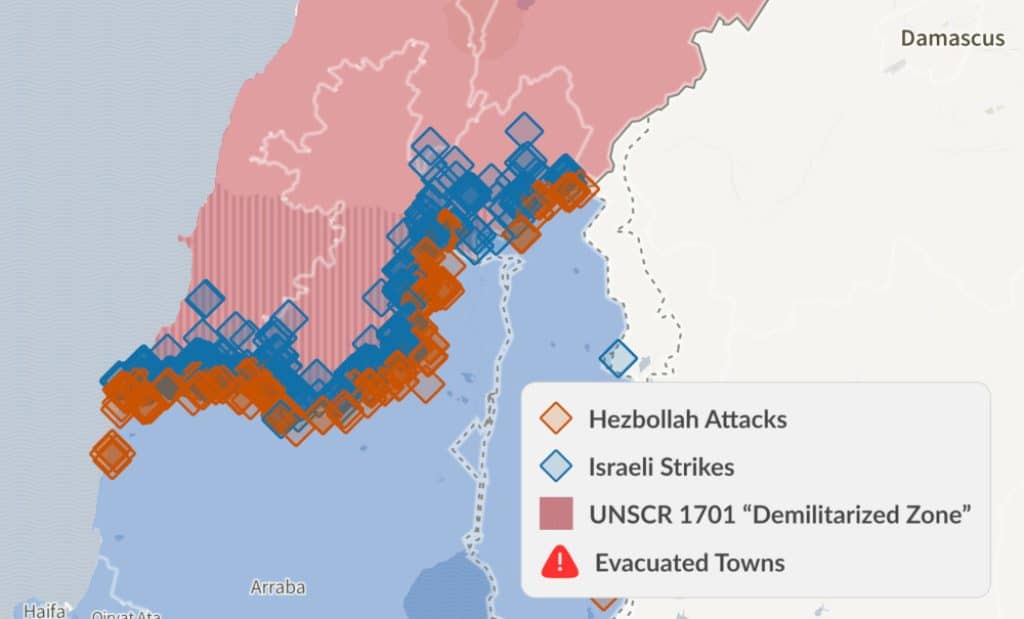

In the early stages of the escalation between Hezbollah and Israel, the conflict was characterized by a recurring and almost predictable pattern of hostilities. Skirmishes frequently erupted along the border, with Hezbollah launching rockets and mortars toward Israeli military posts, while Israel responded with targeted strikes against Hezbollah cells and the sources of fire. Though intense at times, these exchanges remained largely localized, focused on border towns.

Hezbollah’s attacks served multiple purposes for the group: a show of solidarity with Hamas in the wake of the October 7 assault and a means to divert Israeli attention from the Gaza Strip, as iterated by Hezbollah’s former Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah in his November 3 speech. Initially, the group exercised caution in its use of advanced weaponry, such as loitering munitions, as it sought to avoid provoking a large-scale Israeli retaliation. However, as the group’s conflict with Israel evolved, the Israeli incursion into Gaza deepened, and US-Israel relations grew more tense as a result, these more sophisticated arms became a staple in Hezbollah’s arsenal, marking a shift in the intensity of the group’s operations.

Israel’s strategy in the initial days was equally measured. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) concentrated Israel’s early retaliations on immediate threats. However, as the conflict progressed, Israel broadened the scope of its strikes, increasingly targeting Hezbollah’s infrastructure in southern Lebanon as well as operational commanders. This tactical shift aimed to degrade the group’s logistical and military capabilities.

As both sides adapted to the evolving conflict, their tactical approaches became more aggressive, though they did not cross the threshold into all-out war. Their strikes intensified, with Hezbollah adjusting its actions in response to shifts in Israeli tactics that became more aggressive to force the group to decouple Lebanon from a Gaza ceasefire. For example, Israeli strikes on high-level operational commanders in southern Lebanon would prompt Hezbollah to escalate its attacks on northern Israel, often by temporarily expanding the scope of its targets or increasing the volume of munitions used. After these escalations, Hezbollah typically reverted to its routine attacks on IDF positions along the border.

Israel’s strategy can be described as carefully testing the boundaries of engagement. By periodically escalating hostilities, Israel gauged Hezbollah’s responses to determine whether to set the new escalation as a regular tactic. If Hezbollah’s retaliations remained measured and within Israel’s expectation—maintaining the same intensity without crossing red lines, such as military or civilian casualties or serious damage to an IDF base or Israeli population center—then these escalations would become normalized as part of Israel’s operational routine.

For instance, in mid-November, Israel initiated targeted strikes on Hezbollah’s Radwan commanders in the village of Beit Yahoun. Hezbollah’s response, a rocket attack on the headquarters of the IDF’s 91st Division, had a minimal impact on the base and caused zero casualties. This limited retaliation reinforced Israel’s assessment that it could continue its targeted strikes on Radwan commanders in southern Lebanon with little fear of intensification from Hezbollah.

This situation culminated with Israel’s assassination of Hezbollah Chief of Staff Fuad Shukr in the heart of the group’s Dahiyeh stronghold on July 30. Israel had crossed all of Hezbollah’s red lines with the strike, and the group’s underwhelming response on August 25 revealed its limits. From then on, Israel could escalate to tip the weight of attrition heavily against Hezbollah—including by assassinating Nasrallah—while being virtually assured the group had hit its ceiling of violence.

It was necessary for Israel to press Hezbollah in this manner, for it faced two equally unpalatable alternatives. The first was to accept Hezbollah’s (and the collective Axis of Resistance’s) terms and cease military operations in the Gaza Strip. This acquiescence would have bought Israel immediate quiet but allowed Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and other allied militant groups to survive, regenerate, rebuild, and resume attacking Israel. It would have also left Israeli deterrence in shambles, as the Resistance Axis would have succeeded in imposing terms upon Israel—so soon after the massive setback of October 7. It would also have allowed Hezbollah to claim the unprecedented victory of pushing Israelis out of Israel itself for the first time in the country’s history and that its largesse, not the IDF’s efforts, returned them home—which could have boosted Hezbollah’s popular support.

The second, equally unpalatable outcome was for Israel to accept American or French ceasefire deals. These initiatives, whose failure was predictable from the outset, proposed to distance Hezbollah a mere handful of kilometers from the frontier—far below the Litani River, as required by Resolution 1701. The terms also lacked a credible enforcement mechanism to prevent the group’s return from even that limited buffer zone. There were no suggestions regarding disarming the group.

In parallel, the proposed ceasefire deals offered several incentives to the Lebanese government—including funds to rebuild Hezbollah-dominated south Lebanon, assistance in resolving Beirut’s two-year presidential deadlock, and territorial concessions from Israel in disputed frontier areas—even though it was exploiting Hezbollah’s attacks to obtain these benefits. These diplomatic initiatives, while ostensibly aimed at preventing further escalation, would have merely delayed an inevitable Israel-Hezbollah confrontation, virtually ensuring it would be more destructive when it finally happened. In any case, Hezbollah rejected these deals, refusing to decouple a Lebanon ceasefire from one in Gaza.

Peaceful resolutions having run their course and Hezbollah’s limitations already laid bare, Israel set returning its civilians to their homes in the north as a war goal and decided to break the stalemate. It escalated the fight against Hezbollah, dealing the organization several heavy blows in rapid succession to make the group’s commitment to bombarding northern Israel unsustainable. But even as the Israelis have tilted the pain of the war of attrition to weigh heavy upon Hezbollah, the group is nevertheless unlikely to back down—suggesting the current Israeli escalation may be an intermediate phase preceding an even larger operation against Hezbollah.