Now on its fourth day, Ukraine’s surprise offensive in Russia’s Kursk region is a daring gambit likely intended to divert Russian forces and snatch back the war’s momentum. But it also comes with major risks for a Ukrainian military short on reserves and struggling to hold back Russian advances in Donetsk Oblast.

What we know so far

Much about the Ukrainian offensive is still unclear. Kyiv has remained tight-lipped, and Ukrainian units have released scant battlefield footage. What little information is available comes chiefly from Russian-released videos as well as a whirlwind of unconfirmed—and often contradictory—reports on Telegram.

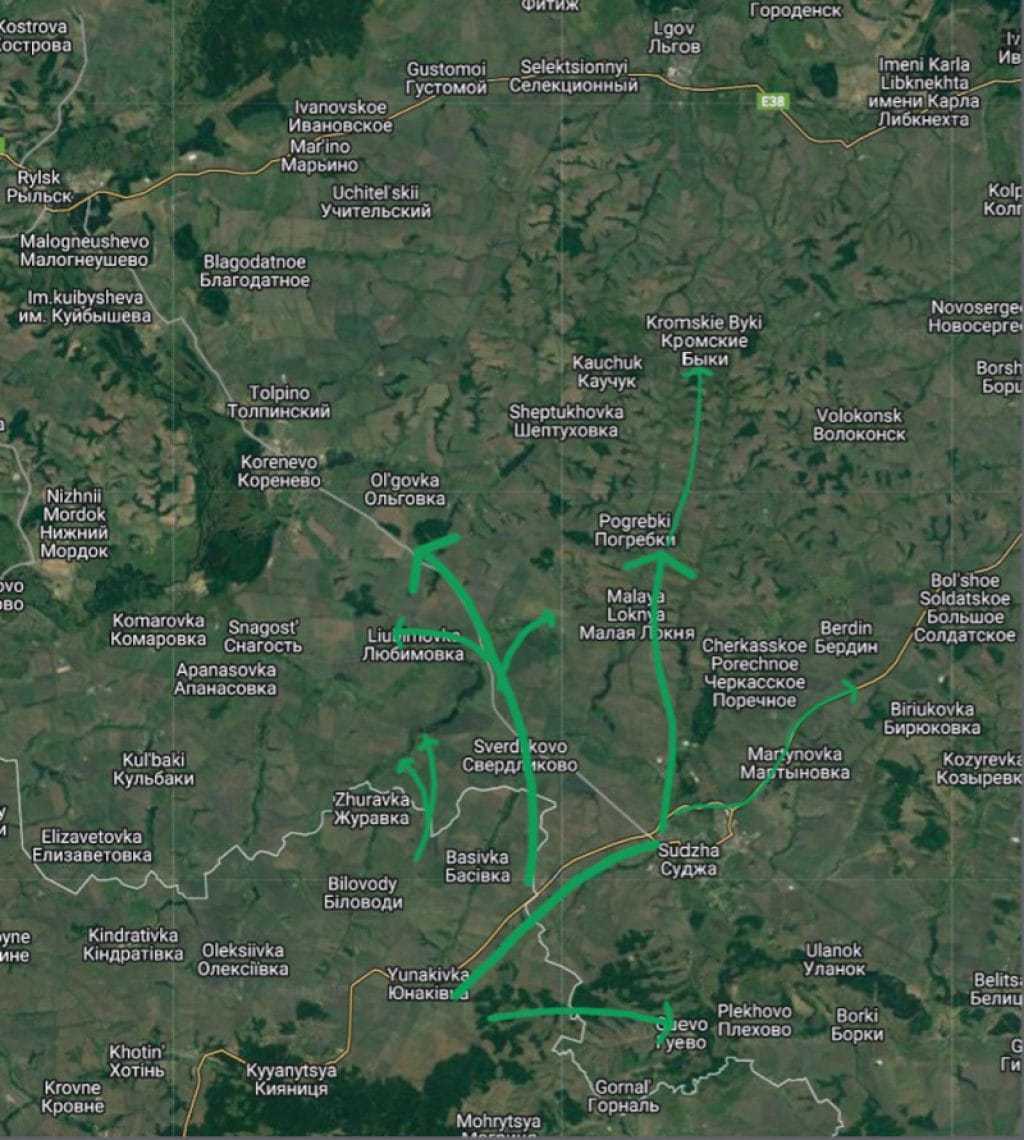

Here is what we currently know: Following an artillery bombardment, Ukrainian forces attacked across the border between the Sumy and Kursk regions on the morning of August 6. They initially advanced in two directions: east to the border town of Sudzha and north toward the town of Korenevo.

Though the attacking force’s precise size and composition remain unclear, the offensive is certainly larger in scale and ambition than Ukraine’s previous cross-border operations. Those raids were conducted by units subordinate to Ukrainian military intelligence, whereas this offensive includes regular forces.

At this point, Ukraine has probably committed battalions from at least several different brigades. The attacking forces appear to have mainly included mechanized and motorized infantry, plus some tanks along with engineering vehicles to clear mines and other obstacles. Ukrainian self-propelled artillery seems to be supporting the advancing forces.

At first, Russia’s Defense Ministry said the initial attack comprised up to 300 troops from Ukraine’s 22nd Separate Mechanized Brigade, equipped with 11 tanks and 20 other armored fighting vehicles. But General Valery Gerasimov, chief of the Russian General Staff, later claimed it involved up to 1,000 troops. Whatever the size of the initial attack, additional forces have likely followed.

Drone crews from the 14th UAV Regiment’s “Nakhtigal” Battalion, the SBU security service, and the 80th Separate Air Assault Brigade apparently also participated in the initial attack. Maneuver units from the 80th Brigade were probably involved, too. Videos of Ukrainian columns posted on Telegram on August 6–7 showed US-donated Stryker infantry carrier vehicles. The 80th Brigade is one of a handful of Ukrainian units known to operate Strykers. Forces from the 116th Mechanized Brigade and 61st Mechanized Brigade are also participating in the offensive. However, this list is likely not exhaustive.

Although there had been warnings about a Ukrainian buildup in Sumy Oblast in the days prior to the offensive, the attack evidently caught Russia off guard. Ukrainian operational security seems to have been tight. Russia left the border weakly defended, protected mainly by conscript and border guard units. (Note that in the Russian system, conscripts—people completing their obligatory one year of military service—are distinct from mobilized troops and prohibited from fighting inside Ukraine.) The Russian defense was prepared to stop small-scale raids but not a sizeable force. Ukraine exploited this surprise with a highly mobile force that advanced rapidly into Russian territory, overrunning or bypassing defensive positions near the border.

Ukrainian forces surrounded and ultimately captured some 50 Russian troops at the Sudzha border checkpoint. Ukraine reportedly met minimal resistance at the nearby village of Oleshnya and also surrounded Russian troops in Gornal, south of Sudzha. The Ukrainians quickly reached Sudzha’s environs and appear to have taken at least part of the town. But a large chunk of the Ukrainian force seems to have turned left at Sudzha, pressing northward along the road connecting that town to Lgov. As of August 8, Ukrainian troops had reached Malaya Loknya, a village roughly 13 kilometers from the border, though they apparently met at least some resistance there.

Meanwhile, Ukrainian forces pressed north from the area around the villages of Dar’ino and Serdlikovo after reportedly meeting some initial resistance. Footage released on social media indicates that by August 7, the Ukrainians had progressed at least 12 kilometers from the border to the area around Novoivanovka.

Some Russian Telegram channels have reported fighting near Korenevo to the northwest, Anastas’evka and Kromskie Byki to the north, and Bol’shoe Soldatskoe northeast of Sudzha. Some of these claims are disputed, however. These reports may reflect Ukrainian sabotage-reconnaissance groups operating ahead of the main force.

Video footage indicates Russia has used attack helicopters and Su-25 attack aircraft, artillery fire (including Krasnopol laser-guided shells), Lancet loitering munition strikes, and Iskander-M ballistic missile strikes to support ground troops trying to stem the Ukrainian advance. In addition, reports by the Ukrainian General Staff and the Sumy regional government, along with Russian–released footage, indicate Su-34 strike fighters have launched many dozens of glide bombs at targets in the Sumy and Kursk regions.

Ukraine has shot down at least one Ka-52 attack helicopter. However, Kyiv has a dearth of air defense systems, and pushing them forward to cover advancing troops renders the systems more vulnerable. A transporter erector launcher and radar from a Buk-M1 medium-range system were likely destroyed by an Iskander missile strike near the border on or around August 6.

Russia has begun dispatching forces to try to contain and roll back the Ukrainian advance, though it remains unclear exactly which units Moscow has sent. What is known is that a Chechen spetsnaz detachment that had been fighting in northern Kharkiv Oblast claims to have redeployed to Kursk on August 6. Russia reportedly also sent forces from the “Pyatnashka” Brigade, which had been fighting at Chasiv Yar in Donetsk Oblast, as well as a detachment of former Wagner Group fighters.

Russian tanks were seen moving on August 7 and 8. Their tactical symbols indicate they came from Russia’s “Sever” grouping, responsible for northern Kharkiv Oblast and Russia’s Bryansk, Kursk, and Belgorod regions. Moscow probably had at least some available reserves in those regions or elsewhere in Russia. Russian heavy equipment is likely arriving in Kursk Oblast in greater numbers as of August 9. Ukraine has sought to interdict the Russian reinforcements, in one case, destroying a truck column carrying infantry near Rylsk.

Ukrainian objectives

For Ukraine, this offensive likely has multiple aims. First, Kyiv seeks to compel Russia to divert forces from other fronts, much like Moscow’s Kharkiv offensive in May 2024 did to Ukraine. This goal could be to relieve pressure in Donetsk Oblast, where Ukrainian troops are struggling to hold back Russian advances, or to enable Ukraine to recapture Russian-controlled territory in northern Kharkiv Oblast.

Second, Kyiv likely sought to reinvigorate Ukrainian morale and Western confidence in Ukraine, reversing the downbeat narrative that has taken hold over the last 10 months. On that score, Ukraine has already achieved some success. The operation has electrified the Ukrainian and Western media while sparking alarm and fury in Russia.

A possible third aim could be to gain leverage in potential peace negotiations. Russian sources report that Ukrainian troops have begun digging in, suggesting Kyiv seeks to hold the captured territory at least temporarily.

The risks of the operation

Despite its initial successes, the Kursk offensive comes with serious risks. Most immediately, Ukraine’s rapid advance has elongated its supply lines and may have created narrow salients whose flanks are vulnerable to Russian counterattacks. If Russia can bring significant forces to bear before Ukraine can widen those salients and organize a robust defense, Ukrainian troops could be cut off. It is unclear exactly what proportion of the Ukrainian forces available for this operation have already been committed.

In the bigger picture, Ukraine took a gamble by committing its limited reserves to the Kursk offensive rather than reinforcing its defense in Donetsk Oblast, where those forces arguably would have been better used. Russia is currently grinding its way toward the city of Pokrovsk, a key logistics hub. Russian troops have also reached the outskirts of Torestsk and are attempting to push deeper into Chasiv Yar.

Russia’s rate of advance has quickened in recent weeks, mainly due to Kyiv’s shortage of manpower. This has been the Ukrainian military’s chief problem since last year. Defending units simply lack enough infantry to hold positions.

“It’s madness. We are fighting with cooks, electricians, and mechanics,” one Ukrainian brigade commander fighting in Donetsk Oblast recently lamented. In the spring, Kyiv took steps to begin redressing the shortage, including bypassing long-delayed legislation to expand its pool of mobilization-eligible men. Ukrainian officials say the mobilization rate has since surged, but the problem will take time to fix. Fresh troops must be trained, and Ukraine’s training pipeline has limited throughput capacity.

Kyiv seems to have scraped the bottom of the barrel to put together forces for the Kursk offensive. The 80th Air Assault Brigade, one of the units apparently participating in the Kursk operation, was in the middle of reconstituting after tough fighting in the Donetsk Oblast. In late July, a scandal erupted when the 80th Brigade commander was demoted for refusing orders he deemed “unrealistic” given his brigade’s current staffing and readiness level. One can now guess he was referring to the Kursk offensive.

The worst-case scenario for Ukraine is that Russia manages to drive back and severely attrite Ukrainian units in Kursk Oblast without meaningfully weakening its position on other fronts. Given Russia’s advantage in force availability, that is not implausible. Currently, there is no evidence Russia has diverted forces from the Pokrovsk axis (its main effort) or the Toretsk axis, and Moscow likely has sufficient forces elsewhere to avoid having to do so.

Even if Ukraine manages to hold territory in Kursk Oblast, those forces will be unavailable for use elsewhere. The operation could take on a life of its own, sucking in more resources than initially intended.

The Kursk offensive may turn out to be a masterstroke that wrests back momentum from Moscow. Or it could be a self-inflicted error that compounds Ukraine’s manpower shortage even as its defense in Donetsk Oblast continues to deteriorate. Only time will tell.