The Levant has been on unusually high alert since a Falaq-1 missile fired by Hezbollah struck a soccer field in the community of Majdal Shams in the Golan Heights, killing 12 Israeli children. Israel’s inevitable response had to be harder and different from any of its strikes in Lebanon since Hezbollah initiated a war of attrition against the Jewish State on October 8.

On the evening of Tuesday, July 30, Israeli aircraft targeted a building in the Haret Hreik neighborhood in Hezbollah’s stronghold in Beirut’s southern suburb of Dahiyeh, killing Fuad Shukur, one of Hezbollah’s most senior and storied military commanders, alongside four civilians. Israel shortly announced that the assassination attempt was successful. But as all awaited Hezbollah’s confirmation—which would come the next day—Hamas political leader Ismail Haniyeh was assassinated in Tehran. As far as it can be determined, he was killed by a bomb smuggled into his Tehran apartment months ago.

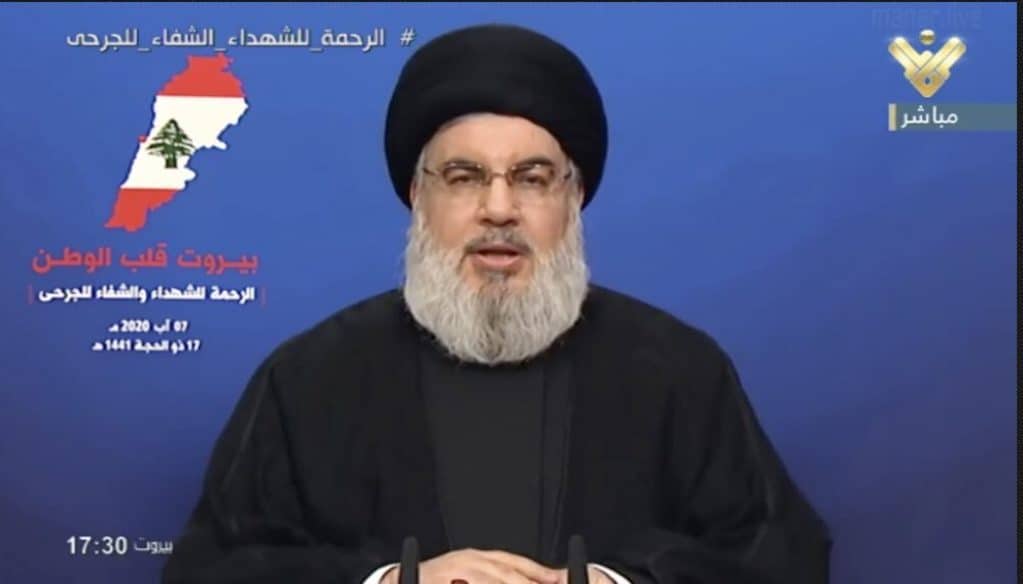

The dual assassination of these two senior Iran-led Resistance Axis figures put the region on the precipice of an escalation. The first indication of how the Axis would respond to the assassinations reportedly came from its Supreme Leader himself. Ali Khamenei reportedly ordered Iran to strike Israel directly for assassinating Haniyeh on Iranian soil. The Houthis also hinted they would participate in the retaliation. But the critical question—because of its proximity and lethality—was how Hezbollah would respond to Israel’s brazen violation of its perceived sanctum in Beirut, the assassination of its top commander, and the collective assault on the Resistance Axis. Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah spared no time providing an answer—albeit one clouded by his typical mixture of exaggerated belligerence and opacity.

Nasrallah devoted the first part of his speech to denying Hezbollah’s responsibility for the Majdal Shams massacre, directed to his domestic audience—first Hezbollah’s base and then the Lebanese Druze community. Nasrallah insisted the impact and casualties were caused by an errant Iron Dome interceptor that fell short in the soccer field where the children were located, falsely insisting that “strategic and military experts” backed his group’s claims.

At 18:18 local time on July 27, Red Alert sirens sounded in Israel, warning of an incoming missile on Majdal Shams but providing little notice to local residents because of the projectile’s short flight time. The projectile impacted the soccer field approximately nine seconds later. At 19:29 local time, Hezbollah issued a statement claiming to have targeted the “Maaleh Golani” headquarters of the IDF’s HeHarim Brigade—a typical time-lag between the organization conducting an attack and issuing a claim for it—with a Falaq-1 rocket, precisely the type of munition the IDF later identified impacting Majdal Shams. Moreover, footage of the projectile’s impact in Majdal Shams shows a massive explosion more consistent with the Falaq-1’s 50kg warhead than the 11kg of explosives carried by an Iron Dome “Tamir” interceptor. In all likelihood, Hezbollah had indeed intended to target the “Maaleh Golani” site, but the Falaq-1, an imprecise weapon, overshot its target and hit the soccer field in Majdal Shams, approximately 3km south but still within the Falaq-1’s 10km range.

Nevertheless, Nasrallah stressed Hezbollah’s innocence, relying on little more than the weight of the group’s denial, his false claims Israel had not presented evidence of Hezbollah’s responsibility, and his assurances that the organization would have admitted striking Majdal Shams by accident.

However, the identity of the victims of the Majdal Shams strike—Israeli citizens, yes, but Arab Druze children—complicates any such admission by Hezbollah. First, the group insists on an image of unimpeachably clean hands as a contrast with Israel’s allegedly ‘murderous bloodthirst,’ and killing 12 children contradicts that image dramatically. Furthermore, because the children were Arab, admitting responsibility for their deaths would have a negative domestic impact upon Hezbollah, particularly among its Druze co-religionists in Lebanon, where the group is trying to cause as few social shockwaves as possible, and with the restive Druze of Sweida in Syria. Finally, Hezbollah has an interest in presenting the Israeli strike in Dahiyeh as yet another example of Israel’s gratuitous aggression, as Nasrallah did, rather than a proportionate retaliation for the murder of its citizens.

Much of Hezbollah’s support derives from the perception among its supporters that the organization is strong and capable of militarily defeating Israel at any time. Therefore, Nasrallah then turned to projecting strength and downplaying—as he has throughout the conflict—Israel’s military accomplishments in Gaza and against Hezbollah and the impact of Shukur’s death on the organization.

“The martyr [Shukur] got what he wanted […] he always used to request a martyrdom operation,” Nasrallah said, stressing that Shukur’s death would neither impact the organization’s determination to fight Israel nor its ability to do so. “We have leaders and generations of leaders […] the martyrdom of any of our leaders will be immediately filled by the jihadi commanders and the students of these commanders,” he insisted.

As part of this attempt to project strength and invulnerability, Nasrallah then turned to threatening the Israelis. “Laugh a little” over killing Shukur and Haniyeh, he told his adversaries, “but you will cry much, because you do not know the red lines which you crossed”—before vowing Hezbollah would settle the score sooner rather than later.

What Hezbollah’s response will look like, however, remains a relatively open question. Nasrallah stressed that after the dual assassinations, the ongoing clashes between the broader Resistance Axis had now become an “open battle on all fronts.” He further emphasized that this battle had “entered a new phase […] a new and different phase from the prior one.” However, this is not the first time Nasrallah has made this exact threat, and it did not signal the group’s intention or desire to transition to a full-scale war. Indeed, he cryptically ended his sentence by noting that further “escalation [in this new phase] depends on the behavior and the reactions of the [Israeli] enemy.”

While Hezbollah’s typical ‘we do not desire war but are ready for it’ formulation was absent from Nasrallah’s speech, the Hezbollah secretary-general offered other hints signaling a disinterest in full conflict. For one, Nasrallah kept the option open for a ceasefire in Gaza, upon which Hezbollah previously preconditioned the cessation of its attacks against Israel. He stressed that “those who do not want [the situation] in the region to deteriorate must seriously pressure and obligate Israel to stop its aggression on Gaza. […] The only solution is to stop the aggression on Gaza.” Nasrallah also said that Hezbollah would resume its routine attacks the day after his speech (though, in reality, they began later the same day), stating these would be separate from the retaliation for Shukur. He also suggested that the revenge attack would only be an escalatory punctuation amidst these attacks rather than a shift to full-scale war.

Admittedly, Nasrallah was enigmatic about Hezbollah’s intentions, and any calming messages in his speech could be a deception meant to lull the Israelis into a false sense of security before launching a war. But of all the options available to Hezbollah, this is the least likely. The domestic factors constraining Hezbollah’s freedom of action for years—namely, Lebanon’s economic collapse and its consequences—that led it to launch a war of attrition on October 8 rather than a full-scale war remain operative.

More likely options would be a revenge that would, in many ways, mirror the Israeli strike in Beirut. The strike will have to walk a very fine line between settling the score over Shukur and reinforcing Hezbollah’s red lines but remain below the threshold that would ignite a full-scale war between Israel and Hezbollah or a regional war.

Here, Hezbollah has several options: It could conduct a painful retaliatory attack, albeit still a limited one, and leave it to its propaganda outlets to magnify the significance and casualties it caused. Alternatively, Hezbollah could attack Israel in tandem with whatever response the Iranians and the rest of the Resistance Axis are planning over Haniyeh’s assassination—the intensity of its strikes absorbed into the collective aggression of the Iranian-led alliance.

Finally, Hezbollah has been cultivating assets within Israel for decades and might potentially activate one of them to carry out an attack on Israeli soldiers or civilians that would originate from behind Israeli lines. This option would cause Israel sufficient pain for killing Shukur and striking inside Beirut but give Hezbollah enough distance and plausible deniability to avoid escalating matters into a full conflict.