Scholars and practitioners in the counter-terrorism or jihadology spheres are by now more than familiar with the Islamic State’s Central Africa Province (ISCAP), better known locally as the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), and its reign of terror in both the DR Congo and its native Uganda.

Lesser known, however, are the origins, characteristics and ultimate fate of a splinter faction that rejected the ADF’s pledge of allegiance to the Islamic State, known by the innocuous-sounding moniker of the Pan-Ugandan Liberation Initiative (PULI).

Splits over doctrine, tactics, personal animosities, and other factors have long caused vicious infighting between jihadist groups, leading the vast majority of jihadist insurgencies to align with either the Islamic State or Al Qaeda. PULI’s relatively small size and limited activity has obfuscated these dynamics within the ADF, as well as their consequences.

As ties between the ADF and Islamic State developed, the group was not immune to these schisms, and its motivations, internal discourse, and evolution into an Islamic State province bears far more semblance to its counterparts across the continent than most scholarship has previously suggested.

Relying on primary source information obtained by the authors through interviews with former members, this article seeks to provide a brief background on the ADF’s now-defunct splinter faction, which for a time represented a second jihadi threat to Uganda (albeit a much smaller one).

As such, this article sheds light on its origins, ideology, key commanders and personnel, information on claimed or potential attacks, its estimated areas of operation, external operations and support networks, and its violent demise at the hands of the larger Islamic State-loyal group.

Origins of the Splinter

The origins of PULI are directly related to the ADF’s relationship with the Islamic State. Following a 2014 offensive by the Congolese army that severely debilitated the ADF, its longtime leader and primary financier Jamil Mukulu fled eastern Congo and was arrested in 2015 in Tanzania. In Mukulu’s absence, his deputy and veteran qadi [Islamic judge], Musa Baluku, took over the mantle as ADF’s emir, leading the group on the ground as it struggled to survive and rebuild.

With a combination of a more radical and global jihadi outlook and shrinking coffers, Musa Baluku looked abroad for support. Over the course of 2016 and early 2017, two influential jihadis, the Ugandan Meddie Nkalubo and the Tanzanian Ahmad Mahamood (a.k.a Jundi or Abuwakas), joined the ADF and steered Baluku towards the Islamic State via their own ties to the global jihadi organization.

Baluku first sought Mukulu’s permission to establish ties, but communications with Mukulu in prison made it very clear that the group’s longtime leader strongly opposed a formal relationship with the Islamic State. But in 2017, Baluku disregarded Mukulu’s directives and offered his group’s loyalty to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and his proclaimed caliphate, which formally accepted his pledge of allegiance in October of that year.

Almost immediately, the ADF began to receive much needed financial support through the Islamic State’s money laundering networks, in addition to an attempt by the Islamic State to send envoys carrying drones and cameras.

In pledging bay’ah [allegiance] to Baghdadi, however, Baluku had to squash intense discontent from people within the ADF who remained loyal to its former leader, Jamil Mukulu. As a result, Baluku ordered the public beheading of select ADF members who disagreed with the group’s newfound loyalty, which saw high-level commanders and at least two children of Mukulu killed by the hands of Baluku-loyal (and by extension Islamic State-loyal) commanders.

It is within this context that a small group, led by long-time ADF commanders Muzaaya (real name unknown) and Benjamin Kisokeranio, himself the son of a co-founder of former ADF ally the National Army for the Liberation of Uganda (NALU), broke away in early 2018 and started their own group in the Congolese bush.

While not initially involved with its creation, one of Mukulu’s sons, Hassan Nyanzi, who was living in South Africa at the time, joined Muzaaya and Benjamin in the jungle shortly thereafter. Former PULI members are consistent that Nyanzi then became the de-facto leader in the bush, with Muzaaya acting as his second-in-command.

The trio then decided to name the splinter a relatively innocuous name, the Pan-Ugandan Liberation Initiative, in order to mask the group’s true intentions and ideology – which is not unlike the use of the name ADF by the parent faction.

And despite his current imprisonment at Uganda’s infamous Luzira Prison, former members of PULI all detail that the group’s three main leaders considered Jamil Mukulu to be the overall emir. It is unclear what practical role Mukulu played, if any, within PULI during its existence.

PULI’s Ideology

Former members of PULI also described to the authors that despite the disagreements over allegiance with the main faction, PULI remained steadfastly jihadist. Indeed, former members describe Nyanzi (known as Audi in the bush), Muzaaya, and PULI’s main imam, Seka [sheikh] Brian, a Rwandan of Ugandan origin, as preaching the virtues of engaging in jihad.

Former PULI members detail that standing in stark contrast to the Baluku-led faction, however, the three preached that non-Muslims are not to be directly targeted in jihad. Instead, only those who actively oppose Muslims are ‘legitimate’ targets in jihad. As such, PULI’s policy on civilian targeting – at least nominally – stood much closer to al-Qaeda’s more restrained directives than the far more indiscriminate justifications for atrocities offered by the Islamic State.

Indeed, while there remains no evidence whatsoever of any bay’ah to or support from al-Qaeda, PULI’s leaders also reportedly expressed their support for Osama Bin Laden, Abu Ubaidah of Somalia’s Shabaab, and even the Afghan Taliban. That PULI’s leadership expressed some degree of ideological affinity for al-Qaeda is an interesting addition to longstanding debates over the degree to which the ADF had ties to global jihadism during the Mukulu era.

Ugandan authorities frequently claimed a relationship, often interpreted by observers as an attempt to curry favor with Western governments during the height of the War on Terror. While Mukulu never established the kind of fully integrated relationship between the ADF and al-Qaeda that groups like Shabaab did, evidence does point to repeated contacts, at least for a period of time.

For instance, the United Nations’ Group of Experts on the DRC reported that Mukulu’s son, Hassan Nyanzi was bailed out of a Kenyan jail in 2011 by Shabaab operatives in the country. This follows other reports of ties between the ADF under Jamil Mukulu and Shabaab, including reports of Somali, Moroccan, and Pakistani trainers in the ADF’s camps.

Al-Qaeda does not require a pledge of bay’ah prior to providing support as the Islamic State does, and this relatively limited relationship may have been a failed attempt on al-Qaeda’s part to bring Mukulu into the fold of transnational jihadism.

In any case, testimonies of former members make clear that PULI’s leadership maintained a rhetorical affinity for al-Qaeda, and its internal narratives about the Islamic State-loyal main ADF faction closely mirrored al-Qaeda’s own rhetoric towards the Islamic State.

PULI’s leadership reportedly lambasted both the Baluku-led faction and the Islamic State writ large as “khawarij,” or extremist deviants of Islam, which is itself a favored descriptor of the Islamic State by al-Qaeda and its various branches, affiliates, and allies.

PULI’s leadership also disagreed with Baluku’s more global jihadi outlook, instead seeking and fighting to just overthrow Uganda’s longtime president, Yoweri Musevenei, and subjugate Uganda under shari’a law.

This stated objective retained Jamil Mukulu’s original Uganda-focused jihad and corresponds to al-Qaeda affiliates’ rhetorical and strategic focus on local regimes. It contrasts to the ADF’s adoption of Islamic State’s emphasis on battling global enemies.

Existence in the Congolese Bush

Camping deep in the Congolese jungle, PULI’s relatively short existence, from just early 2018 to January 2023, was at first dull and uneventful before entering a tumultuous state of survival just before its purge by the larger Baluku-led faction. Never comprising more than 150-200 people living in one semi-mobile camp, PULI spent most of its days trying to survive without engaging in much combat.

Former members describe that PULI’s main camp – which went by different names depending on its location – moved often, as it was trying to hide from the main Baluku-led faction and later the Ugandan military. Towards the end of its existence, members describe the camp as moving near-daily to avoid either force.

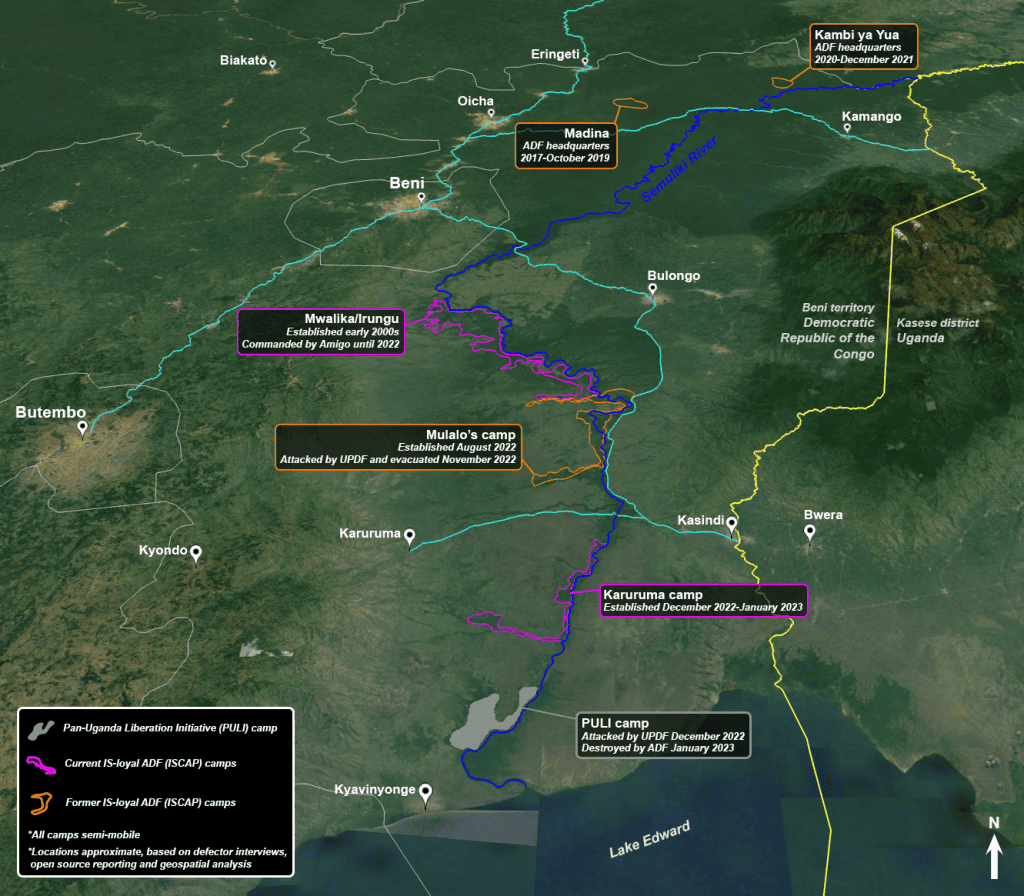

The ADF had long maintained camps in the Mwalika Valley, a large flat plain surrounding the Semuliki River and most of which is technically part of Virunga National Park. While the Baluku-led main faction retained its camps in the northern parts of the valley, PULI opted to entrench itself 30-40km farther south near Lake Edward.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given its more localized jihadi agenda, the vast majority of PULI’s members were Ugandan. However, the group also actively abducted Congolese civilians into its ranks, including one such former member interviewed by the authors.

Many Rwandans were also present, though the vast majority were reportedly of Ugandan origin. Other nationalities, such as Kenyans and Tanzanians, were also reported but in vastly smaller numbers compared to Ugandans (and Rwandese-Ugandans) and Congolese.

Just two former members of PULI confirmed to the authors that the group conducted military operations, with both physically taking part in such combat. The two describe a total of 13 raids or clashes that PULI engaged in during its existence.

The majority of these attacks targeted Congolese military bases in order to capture and stockpile weapons and ammunition. The group also reportedly targeted nearby Mai-Mai groups, or local militias, and the main Baluku-led faction on only one occasion.

Pinpointing the dates and locations of these attacks remains difficult, however. Local reporting does not distinguish between PULI and the main ADF faction, while bandits and local Congolese militia also operate in the area, further muddying responsibility for specific incidents.

External Networks and Alleged Attacks

Much like its parent group in the ADF, PULI also heavily relied on outside support during its time in existence. For instance, former members of PULI interviewed by the authors detail that Hassan Nyanzi would often brag to the camp about receiving financial transfers from supporters in the United Kingdom.

Though these claims are wholly unsubstantiated, the ADF under Mukulu did have a long-history of receiving support from UK-based backers. Nyanzi himself was also once a London resident with his father and possibly maintained communication with the UK-based backers prior to the creation of PULI.

It is thus entirely possible that supporters during the Mukulu-era were reactivated, or repurposed, to help fund the nascent ADF rival, though this angle certainly requires more scrutiny.

At the same time, PULI maintained access to at least parts of the ADF’s extensive recruitment and logistical network throughout Uganda (and potentially beyond) that was established during the Mukulu era. For instance, one former member of PULI explained to the authors how he was recruited inside Kampala, Uganda, and was trafficked to PULI’s camp. His recruiter reportedly transferred several other individuals to the camp during the group’s existence.

Another former member described that when he first joined, there were approximately 50 people. These recruitment networks in Uganda, however, were able to bring in 10-20 people per month before the group reached its max strength of around 150-200 people.

While these are relatively low numbers for a nascent insurgent group, it remains impressive that PULI was ostensibly able to recruit inside Uganda despite pressure from the Ugandan authorities and parallel recruitment networks of the ADF inside Uganda.

PULI’s continued ability to funnel recruits to its camp despite the main ADF faction operating similar, parallel recruitment and supply networks raises questions about how thoroughly the ADF’s support networks have adopted the ADF’s allegiance to the Islamic State and its hardline stance on PULI.

It is possible that these networks or components within them, established long before Baluku pledged allegiance to the Islamic State and often operating through personal and familial relationships, have retained connections to both groups.

Personal relationships within jihadist organizations have often persisted past organizational splits into Islamic State and al-Qaeda aligned factions. While official positions may draw hard lines between groups, their common origins can lead supporters and personnel to maintain ties and even cooperate despite explicit directives to the contrary.

These personal ties are likely a major factor in PULI’s ability to survive as long as it did. Author interviews with Ugandan sources often mentioned a close friendship between Muzaaya and main faction commander Amigo Kibirige. Kibirige had long been amongst the most senior ADF commanders in the Mwalika camps and may have impeded previous attempts to destroy PULI’s camp despite its proximity to his own.

The UN Group of Experts reported that Kibirige was sidelined by Baluku in 2022, who sent a more trusted commander, Seka Umaru, to oversee the ADF’s camps in the Mwalika valley.

Operating farther south in Congo’s Uvira and Burundi’s Bujumbura, PULI co-founder Benjamin Kisokeranio was the group’s main financier and supplier. One former PULI member describes that the camp would congregate to celebrate the arrival of supplies or weapons acquired by Kisokeranio outside of the bush.

Kisokeranio was arrested by Congolese authorities just shortly before the destruction of PULI. It is unclear what impact the arrest of PULI’s primary financial and logistical figure had on the group’s ability to sustain itself.

And though unsubstantiated, PULI has also claimed responsibility for attacks inside Uganda. For example, the group publicly claimed responsibility for the attempted assassination of Ugandan Principal Judge Flavian Zeija along the Kampala-Masaka highway in April 2022.

Another former PULI member stated that Nyanzi also took credit inside the camp for several improvised explosive device (IED) attacks inside Uganda. For instance, a few days prior to the IED against Judge Zeija, another IED detonated along the same highway, wounding two civilians. Another explosion claimed internally was the October 2021 IED on a police post in Kampala’s Kawempe neighborhood.

And though not an IED, Nyanzi also reportedly claimed the June 2021 attempted assassination of Gen. Katumba Wamala, Uganda’s Minister of Works and Transport, according to the same former PULI member.

Both the Kawempe explosion and the attempted assassination of Gen. Katumba Wamala were either publicly claimed by or believed carried out by the Baluku-led faction. The Islamic State, for its part, publicly claimed the Kawempe explosion on behalf of the ADF. The aforementioned IEDs along the Kampala-Masaka road, however, were never claimed by the ADF nor the Islamic State.

It is thus likely that Nyanzi internally took credit for attacks carried out by the Baluku-led faction inside Uganda to help bolster his forces’ morale inside the jungle camp. It is unclear whether Nyanzi learned of these attacks through reports in local media or through contacts within the Baluku-led faction.

PULI’s Destruction

PULI’s ultimate fate was sealed by the Islamic State-loyal main faction in January 2023. A significant raid led by longtime ADF field commander Elias Segujja, also known as “Mulalo” or “Fezza,” pushed south in the Mwalika Valley and attacked PULI’s camp, then existing near the shores of Lake Edward.

Some PULI members were able to escape the raid and surrender to authorities, but most were killed or captured and taken to the main faction’s camps in northern parts of the Mwalika valley.

This final purge came soon after the PULI camp survived an assault on its position from the Ugandan military, which tracked its location. Ugandan and Congolese security forces have seldom if ever made distinctions between PULI and the main ADF faction, either in military operations or public statements. Though the group ultimately survived the military raid, it was weakened and forced to relocate once again.

Waiting in the background, however, were Mulalo’s men who then tracked the PULI movement and reported back to Mulalo’s main camp with the group’s location. From there, Mulalo’s group pounced on the weakened PULI and finally destroyed the ADF’s once erstwhile jihadi rival.

Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, both former PULI and ADF members spoken to by the authors confirm that PULI’s surviving captured members and leaders, including that of Hassan Nyanzi, were welcomed back into the main fold. One former PULI member described that once captured by Mulalo, the PULI members and leadership were personally forgiven by Baluku himself and were thus reintegrated into the ADF’s rank-and-file and hierarchy.

It is particularly noteworthy that Mulalo’s assault on PULI took place amid significant military pressure by the Uganda People’s Defense Force (UPDF) and the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC) in the area under Operation Shujaa, which was launched in late-November 2021.

While the operation began in northern Beni, targeting the ADF’s headquarters near the locale of Kambi ya Yua, it had expanded into the Mwalika Valley and other areas adjacent to the Beni-Kasindi road by April 2022. Operations significantly expanded by the fall, with at least three UPDF battalions deployed west of the Semuliki River.

In November 2022, air strikes targeted Segujja’s camp, forcing a significant relocation. At least part of this force moved southwards, leading to a string of attacks in the southern Mwalika Valley in December. It was thus almost inevitable that the two forces would finally meet head-on, despite years of uneasy coexistence in the same basic geographical area.

To be noted, the UPDF again struck at Mulalo’s camp in February 2023, reportedly killing the veteran commander. However, his alleged death has yet to be conclusively confirmed.

Conclusion

While PULI earned little attention in the shadow of Baluku’s IS-allied faction’s unprecedented wave of violence, PULI’s origins, existence and internal discourse offers some important clarity on the ADF’s transformation since 2016.

Scholarship on the ADF has often minimized the importance of jihadist discourse within the group, framing its relationship with IS as either purely pragmatic or otherwise limited. More recent coverage has often wholly neglected its pre-Islamic State history, as if the ADF began with the Islamic State’s first propaganda release on the ADF’s behalf in April 2019.

The emergence of PULI, the discourse surrounding its creation, and how the group justified the schism to its members suggests that the debates within the jihadist movement over the legitimacy of the Islamic State have salience even within jihadism’s more isolated and unique insurgencies.

Far from being isolated from these arguments, the ADF’s own internal divisions bear close resemblance to those seen in jihadist insurgencies across Africa and around the world. Similarly, the more practical realities of enduring personal relationships within these organizations and rival groups’ access to pre-existing support networks have strong similarities to splits within other jihadist groups.

PULI’s story demonstrates how the ADF’s integration into the Islamic State was contentious and even violent, a process as emblematic of the conflicts seen within the global jihadist movement as it was a product of the ADF’s unique local circumstances.

Both authors are senior analysts at the Bridgeway Foundation, a philanthropic organization dedicated to ending and preventing mass atrocities.