Editor’s note: The review of ‘The Bin Laden Papers’ was originally published at The Washington Free Beacon.

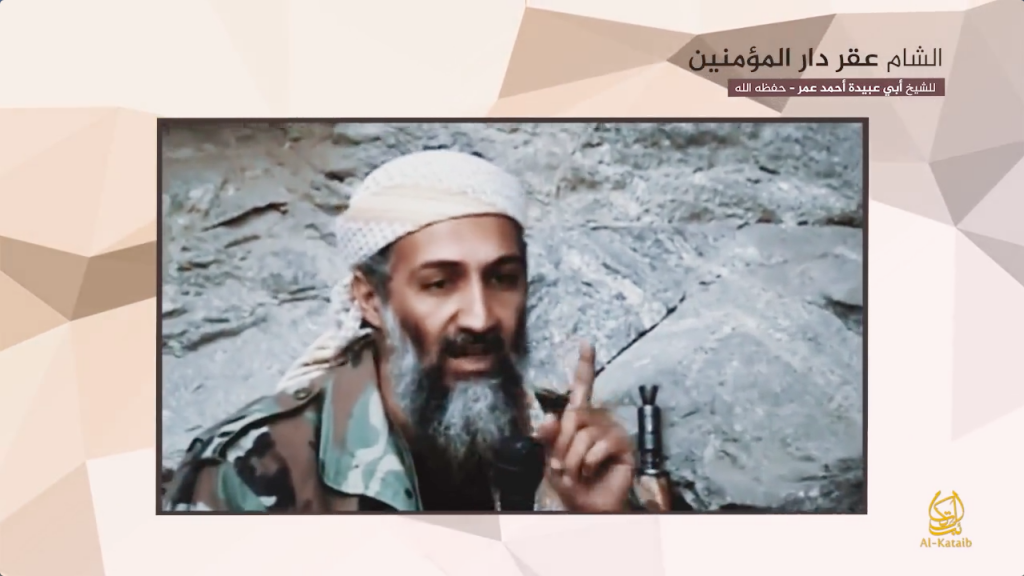

In autumn of 2017, my colleague Thomas Joscelyn was invited to visit the Central Intelligence Agency. It was a long time coming. He and our colleague Bill Roggio at FDD’s Long War Journal had for years pushed the intelligence community to release the complete set of documents that American Navy SEALS captured at Osama bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, on May 1, 2011. The al Qaeda leader was shot dead that night, ending a 10-year search for the man behind the 9/11 attacks.

The intelligence community released a handful of the documents in 2012. They released more in 2016 and 2017. But tens of thousands more remained classified. Joscelyn and Roggio, who had doggedly tracked al Qaeda for two decades, insisted there was no reason to withhold the files from the public.

They had a point. Usually, such documents are classified to protect “sources and methods.” In this case, we knew the source of the documents: bin Laden’s lair. We also knew the methods used to acquire them: the raid.

Notably, my colleagues did not push for the immediate release of the documents. People in the field understood that the intelligence community could exploit the files for additional operations. And they did. Soon after the raid, American forces tracked down other senior terrorists, with lethal success.

But by 2017, the files were growing stale. The arguments for releasing them finally prevailed. When I accompanied Tom to the CIA that day, he was handed a couple hard drives. But there were few smiles in the room. Joscelyn and Roggio had been a thorn in the agency’s side. To return the favor, our interlocutors gave no guide for the files. It was a veritable haystack, with no indication of what the needles even looked like. Many files were infected with viruses. It would take years to get through them all.

Thankfully, the Long War Journal was able to produce some relevant analysis based on a video of bin Laden’s son, Hamza, at his wedding in Iran and several other documents. But it wasn’t much of a head start. The documents were released to the public shortly thereafter.

Five years later, Nelly Lahoud, a senior fellow at New America, has released a book based on roughly 6,000 of those documents. It is no simple task to stitch together a narrative that made sense of the various letters, journal entries, and other missives from bin Laden’s files. Unfortunately, Lahoud’s book only underscores this.

Hers is a narrative that is not particularly easy to follow, even for those who have tracked al Qaeda closely. While largely chronological, the book toggles between the mundane details of the bin Laden family, the scattered trajectory of the terrorist network after the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, and the interplay between various jihadists and their leader in exile. Some of these jihadists are important to the story of al Qaeda. Others are not. And the author struggles to make that distinction. The result is a book that often stumbles from one unsatisfying narrative to another.

Lahoud’s thesis is perhaps best summed up in the last line of her epilogue: “We now know from the Bin Laden Papers that the man whose post-9/11 statements were brimming with threats was in actuality powerless and confined to his compound, overseeing an ‘afflicted’ al-Qaeda.”

But as Joscelyn and Roggio have repeatedly shown, this assertion is false. The files show that bin Laden and his lieutenants managed a sprawling terror network. Through intermediaries, he regularly communicated with subordinates around the globe during the final year of his life. Bin Laden weighed in on key decisions affecting the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Somalia, and beyond. He oversaw plots against the West, all of which were fortunately thwarted or failed. And he tried to rein in the most unruly jihadists in Iraq.

As former acting director of the CIA Michael Morell wrote, the agency was surprised to learn from the documents that bin Laden was not only “managing the organization from Abbottabad, he had been micromanaging it.”

The book’s greatest flaw is that it reads like “finished intelligence.” It cherry picks from the documents to tell a story. Admittedly, nobody wants to read all those documents; most readers would welcome an author’s doing the heavy lifting. But in this case, Lahoud makes some highly controversial assertions while only serving up slices of evidence from the sources she cites.

Lahoud is on particularly thin ice with her treatment of the complex relationship between al Qaeda and Iran. She dismisses the vast body of evidence suggesting the two share a strategic partnership despite their mutual distrust and sectarian tensions. The evidence has been slow but steady over the years. The 9/11 Commission Report, released in 2004, gave clear indications of the ways in which the two worked together. Subsequent U.S. Treasury Department sanctions designations of senior al Qaeda figures operating in Iran have further shaped our understanding of how the world’s most deadly terrorist group and the world’s most prolific state sponsor of terrorism have partnered.

One file found in Abbottabad identifies Yasin al-Suri as a key al Qaeda facilitator based in Iran. Using the bin Laden files, among others, the Treasury Department reported in July 2011 that Suri operated “under an agreement between al-Qaeda and the Iranian government.” The 2021 assassination, purportedly by the Israeli Mossad, of Abu Muhammad al-Masri on the streets of Iran further points to the fact that senior terrorists have roamed free in Iran for years even as other al Qaeda operatives have been under house arrest.

Another complexity that Lahoud glosses over is the relationship between al Qaeda and the Pakistani government. Lahoud suggests throughout the book that the terrorist group was at odds with Islamabad. We know, however, that Pakistani leadership provided assistance and shelter to the Taliban and a wide range of al Qaeda-affiliated actors over the years. This was a significant source of tension with Washington—so much so that the U.S. government declined to inform Pakistan before the Abbottabad raid.

Lahoud emphasizes the tensions that existed between bin Laden and the affiliate groups that pledged allegiance to al Qaeda. While command and control was undeniably a challenge at times, bin Laden held far more sway than Lahoud concedes. And it’s now clear that these affiliates are bin Laden’s primary legacy. Without them, al Qaeda would be confined to its original redoubts in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

It’s unclear why Lahoud chose not to explore the deeper complexities of these issues yet devoted pages of the book to banal poetry written by bin Laden’s third wife, for example. Indeed, questions surrounding the next phase of jihadism, not to mention America’s relations with Iran and Pakistan, remain highly relevant to U.S. foreign policy even as the “War on Terror” is eclipsed by domestic discord in America and escalating great power competition with China and Russia, not to mention the latter’s invasion of Ukraine.

The fight over the release of bin Laden’s files is over. But the battle over how to interpret them continues.