Editor’s note: This analysis was updated on Sept. 22, 2021 to include the additions on Mullah Zakir and Ibrahim Sadr.

The Taliban has announced the formation of an “interim government” to rule over Afghanistan. The Taliban’s regime will be known as the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. This is entirely unsurprising. The first emirate was toppled during the U.S.-led invasion in late 2001. The jihadis, members of both the Taliban and al Qaeda, waged jihad for the next two decades in order to resurrect it. The Taliban was clear about its political goal all along.

Many of the newly appointed leaders in the Islamic Emirate are actually old Taliban leaders. More than a dozen of them were first sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council in early 2001. Some new faces have joined them.

Brief profiles for 24 of the Taliban men who will govern under the emirate are offered below. This list does not include all of the figures appointed to lead. FDD’s Long War Journal will likely add to this list in the future. Many of the Taliban leaders discussed below have either current or historical ties to al Qaeda. Indeed, some of them worked closely with al Qaeda throughout their careers. Some them are U.S.-designated terrorists.

Six of the newly-appointed Taliban leaders were once held at the detention facility in Guantánamo. Five of them were exchanged for Bowe Bergdahl in 2014 and are discussed at the end of this analysis.

Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada is the current “Emir of the Faithful,” or top leader of the Taliban. He has served as the Taliban’s emir since 2016. At some point during the jihad against the Soviets, Akhundzada reportedly fought within the ranks of the Hezb-e-Islami group led by the mujahideen commander Yunus Khalis. After the Taliban took over most of Afghanistan, ruling from 1996 to 2001, Akhundzada was a religious scholar, judge and head of the judiciary branch.

As the top judicial figure, Akhundzada issued fatwas, or religious decrees, justifying all aspects of the Taliban’s operations, including suicide attacks. His son, Hafiz Abdul Rahman, killed himself in a suicide attack against Afghan forces in Helmand province in 2017. Ayman al Zawahiri, the head of al Qaeda, swore allegiance to Akhundzada in 2016. The Taliban’s “Emir of the Faithful” has never disavowed Zawahiri’s oath.

Mullah Mohammad Hassan Akhund is the acting head of state. Akhund was a close compatriot of Mullah Omar. During the Taliban’s first regime from 1996 to 2001, Akhund served as the governor of Kandahar, foreign minister, and first deputy of the Taliban’s council of ministers.

On behalf of the Taliban’s senior leadership, Akhund refused to turn over Osama bin Laden after al Qaeda carried out the August 1998 U.S. embassy bombings — the deadliest attack by bin Laden’s network prior to 9/11. “We will never give up Osama at any price,” Akhund said, after the U.N. threatened to impose sanctions if bin Laden wasn’t handed over. Akhund was sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council in Jan. 2001. As of 2009, Akhund was one of the Taliban’s “most effective” insurgent commanders. He was also member of the Taliban’s supreme council.

Taliban-linked social media accounts have shared multiple images of Akhund in recent days, including photos of him meeting with other senior Taliban officials. One image can be seen on the right.

Sirajuddin Haqqani is the acting interior minister. In that role, he will likely have great power within the Taliban’s newly resurrected Islamic Emirate. Indeed, Sirajuddin issued guidance to the Taliban’s commissions and judges as the jihadists took over the country this year.

Sirajuddin is the son of Jalaluddin Haqqani, who served as a commander in Yunus Khalis’s Hezb-e-Islami group, but became more widely known as a notorious powerbroker in the region. Jalaluddin was the founder of the so-called Haqqani Network, which is an integral part of the Taliban. The Haqqanis have benefited from the support of Pakistan’s military and intelligence establishment.

In Oct. 2001, Jalaluddin was appointed the head of the Taliban’s military forces. In that role, he helped Osama bin Laden escape the American manhunt in late 2001, while also publicly defending the al Qaeda founder. Indeed, Jalaluddin was one of bin Laden’s first benefactors and helped incubate al Qaeda in the Haqqanis’ own camps in eastern Afghanistan during the 1980s. Al Qaeda issued a glowing eulogy for Jalaluddin after the Taliban announced his death in 2018, and continued to honor him in the months that followed.

Years before Jalaluddin’s demise, Sirajuddin inherited the leadership of the Haqqanis’ network. He has overseen it for much of the past two decades. At the same time, Sirajuddin quickly rose up the Taliban’s ranks, serving as one of two deputy emirs to Akhundzada since 2016, as well as the head of the Taliban’s Miramshah Shura.

Sirajuddin has worked closely with Al Qaeda throughout his career, so much so that it is often difficult to tell the Haqqanis and al Qaeda apart. A team of experts working for the United Nations Security Council recently reported that Sirajuddin may even be a member of al Qaeda’s “wider” leadership. Regardless, there is no question that Sirajuddin is an al Qaeda man. The Haqqanis main media arm has even celebrated the unbroken bond between the Taliban and al Qaeda. And al Qaeda’s general command has referred to Sirajuddin and Akhundzada as “our emirs in the Islamic emirate.” The U.S. government has listed Sirajuddin as a specially designated global terrorist, offering a reward of up to $10 million for information leading to his capture and prosecution.

Mullah Yaqoub is the acting defense minister. He is the son of Mullah Omar, the founder and first emir of the Taliban. Omar repeatedly refused to hand over Osama bin Laden to the U.S. both before and after the 9/11 hijackings.

Alongside Sirajuddin Haqqani, Yaqoub has served as one of the Taliban’s two deputy emirs since 2016. Yaqoub was also named as the group’s military commander. Yaqoub previously served as a member of the Quetta Shura and the military commander of 15 provinces.

In a recent video blaming America for the 9/11 hijackings, Yaqoub openly praised the Taliban’s suicide squads, saying they will continue to play a leading role in the defense of the Islamic Emirate. The Taliban did not previously release pictures showing Yaqoub’s face, but some images (including the one on the right and others) were shared via social media within the last day.

Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar is the acting first deputy head of state. Baradar cofounded the Taliban with Mullah Omar, and served at the most senior levels within the Taliban between 1996 and 2001, including as deputy minister of defense. The Trump administration negotiated Baradar’s release from prison in Pakistan, where he was detained for approximately eight years, in order to give negotiations between the two sides the appearance of gravitas. Baradar then headed the Taliban’s delegation in Doha, Qatar and secured the deal that led to the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. That agreement paved the way for the Taliban to seize control of the country. Baradar was sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council in Feb. 2001.

Mullah Abdul Salam Hanafi is the acting second deputy head of state. He was a key member of the Taliban’s Doha delegation, which secured America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan. Abdul Salam has playing a leading role in the Taliban’s diplomatic efforts with China and other powers since the fall of Kabul. He was sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council in Feb. 2001, as he served as the deputy minister of education for the Taliban at the time. Years later, beginning in 2007, the Taliban named him its shadow governor for Jawzjan province. He was also “believed to be involved in drug trafficking,” according to the U.N.

Khalil al Rahman Haqqani is the acting minister of refugees. He has played a leading diplomatic role in Kabul since it fell, accepting pledges of loyalty to the newly restored Islamic Emirate from various parties. Flanked by arm guards, Khalil was also seen preaching in the Pol-e Khishti Mosque, the largest mosque in Kabul. Khalil is a brother of Jalaluddin Haqqani and the uncle of Sirajuddin Haqqani. He has served as a key fundraiser, financier, and operational commander for the Haqqani Network.

When the U.S. Treasury Department designated Khalil as a terrorist in 2011, it noted that he “acted on behalf of” al Qaeda’s military, or “Shadow Army,” in Afghanistan. In 2002, when the U.S. was hunting Osama bin Laden, Khalil deployed men “to reinforce al Qaeda elements in Paktia Province, Afghanistan.” The U.S. State Department’s Rewards for Justice Program has offered a reward of up to $5 million for information leading to his capture and prosecution. It is likely that at least some of al Qaeda’s personnel are considered “refugees” in Afghanistan, meaning they will be included in Khalil Haqqani’s portfolio.

Mullah Abdul Manan Omari is the acting minister of public works. Omari is a brother of Mullah Omar and uncle to Mullah Yaqoub. In 2016, he was named the head of the Taliban’s preaching and guidance commission, which was tasked with spreading “the goals of Islamic Emirate,” while countering the “illegality and aims of the invaders and their stooges,” meaning the Afghan government. He served as a member of the Taliban’s negotiating team in Doha, Qatar.

Mullah Taj Mir Jawad is the acting first deputy of intelligence. Jawad was a leader in what the U.S. military used to refer to as the Kabul Attack Network, which pooled fighters and resources from the Taliban, Al Qaeda, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, the Islamic Jihad Union, the Turkistan Islamic Party, and Hizb-I-Islami Gulbuddin in order to conduct attacks in and around Kabul. The network extended into Logar, Wardak, Nangarhar, Kapisa, Ghazni, and Zabul Provinces. Jawad is a leader within the Haqqani Network. In his new role, Jawad will work with Abdul Haq Wasiq, an ex-Guantanamo detainee discussed below.

Mullah Abdul Qayyum Zakir is the acting deputy minister of defense. Zakir is a former detainee at Guantanamo Bay. After he was released in 2008, served as the head of the Taliban’s Gerdi Jangal Regional Military Shura, a military command that oversees operations in Helmand and Nimroz provinces. In this capacity, he worked closely with Al Qaeda. He led the fight against the U.S. surge in the south, and in 2010 was appointed as the head of the Taliban’s military commission. He resigned in 2014 but remained on the Taliban’s Quetta Shura and led military forces in the south. In 2020 he was appointed to serve as a deputy to military commission chief Mullah Yacoub. He will continue to report to Yacoub.

Ibrahim Sadr is the acting deputy minister of the interior for security. Sadr is a influential military commander who had close ties with Mullah Omar and Mullah Mansour. Ibrahim served on the Taliban’s Peshawar Regional Military Shura and was appointed to lead the Taliban’s military commission in 2014. In 2020, Ibrahim was replaced by Mullah Yacoub, who was named the head of the Taliban’s military commission. Ibrahim was demoted to serve as Yacoub’s deputy. Sadr is listed as a Specially Designated Global Terrorist and was worked with Iran’s Qods Force to improve the Taliban’s fighting capabilities. Under the agreement, “Iranian trainers would help build Taliban tactical and combat capabilities,” the Treasury designation noted in 2018. Sadr will serve under Sirajuddin Haqqani.

Qari Fasihuddin is the acting chief of army staff. An ethnic Tajik, Fasihuddin commanded the Taliban’s forces in northern Afghanistan during the group’s final conquest in the spring and summer of 2021. He also led Taliban troops during the recent offensive in the Panjshir Valley.

Fasihuddin has served as the deputy head of the Taliban’s military commission. He has ties to foreign jihadist groups such as the Turkistan Islamic Party and Jamaat Ansarullah, a Tajik terrorist organization. Fasihuddin was the Taliban’s shadow governor for Badakhshan province. After the province fell in the summer of 2021, he put Jamaat Ansarullah in command of five districts.

Maulvi Abdul Hakim Sharia is the acting minister of justice. FDD’s Long War Journal assesses that this may be the same person as Maulvi Abdul Hakim Ishaqzai, who was the Taliban’s shadow justice minister and negotiator for the group in Doha, Qatar. He is reportedly close to the Taliban’s emir, Haibatullah Akhundzada, and studied at the Darul Uloom Haqqani, a Deobandi seminary that is often referred to as the “University of Jihad.”

Najibullah Haqqani is the acting minister of communications. He was sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council in Feb. 2001. During the Taliban’s first regime, he was the deputy minister of finance. He was the Taliban’s military commander for Kunar province as of June 2008 and worked as the shadow governor for Laghman province as of 2010.

Abdul Baqi Haqqani is the acting minister of higher education. During Taliban rule from 1996 to 2001, he served in various positions, including as governor of Khost and Paktika provinces, and vice minister of information and culture. He was sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council and the European Union for activities on behalf of the Taliban both prior to and after 9/11.

Mullah Hamidullah Akhundzada is the acting minister of aviation and transport. He was sanctioned by the U. N. Security Council in Jan. 2001 for serving as the head of Ariana Afghan Airlines during Taliban’s first rule.

Mullah Abdul Latif Mansoor is the acting minister of water and power. He was sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council in Jan. 2001, due to his role as the Taliban’s minister of agriculture.

He went on to fill a number of other positions, including as a “member of the Taliban Supreme Council and Head of the Council’s Political Commission as at 2009.” He was the Taliban’s shadow governor for Nangarhar province in 2009 and “a senior Taliban commander in eastern Afghanistan” one year later.

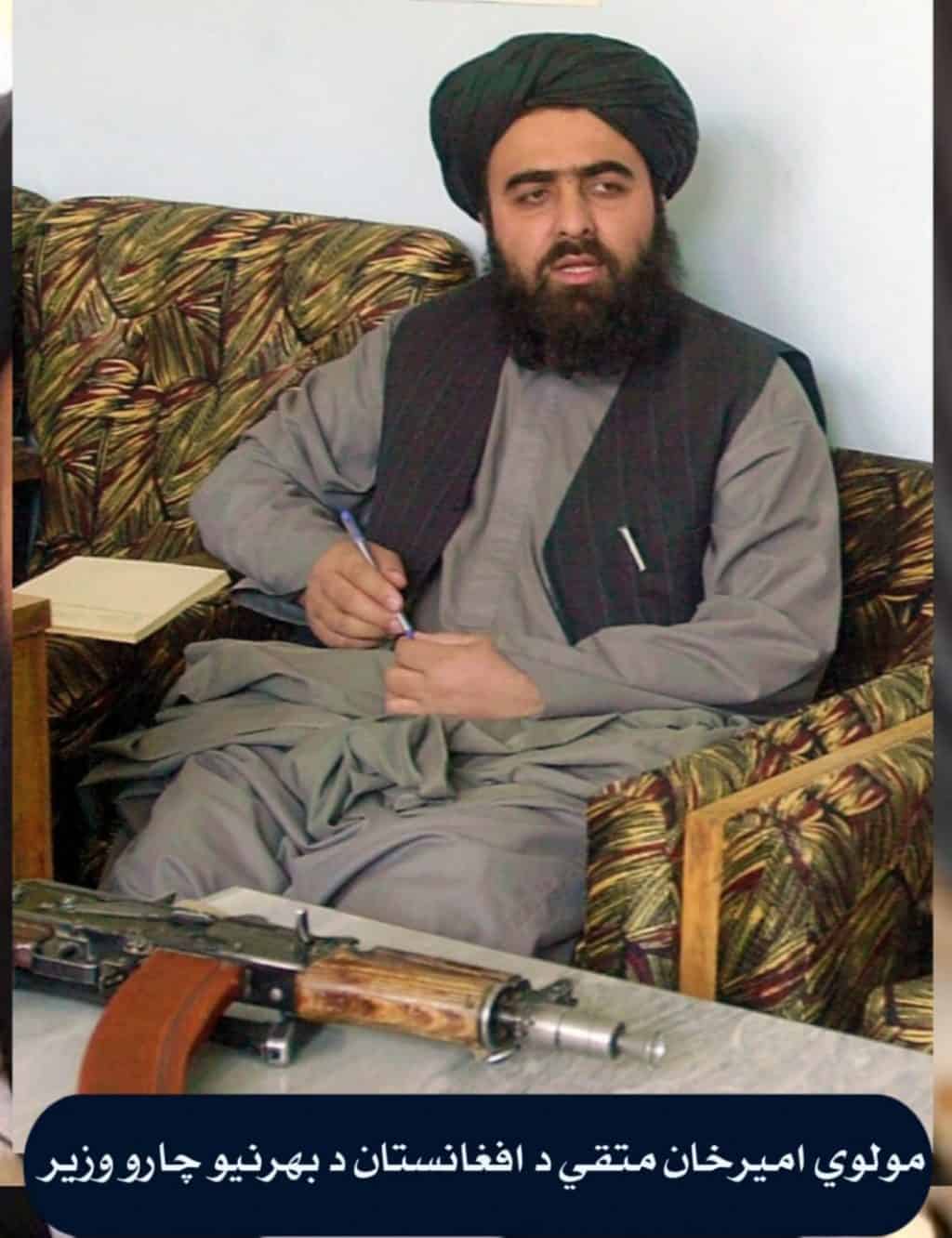

Amir Khan Muttaqi is the acting minister of foreign affairs. Muttaqi was a member of the Taliban’s negotiating team in Doha, Qatar. Muttaqi was sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council in Jan. 2001 for his role as the Taliban’s minister of education.

Muttaqi was the Taliban’s minister of information and culture during the pre-Oct. 2001 regime and also chief negotiator with the U.N. Muttaqi later held a seat on a Taliban regional council, as well as the Taliban’s supreme council.

Maulvi Noor Mohammad Saqib is the acting minister of hajj and religious affairs. Saqib was sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council in Jan. 2001 for his role as the chief justice of the Taliban’s supreme court. He studied at the Darul Uloom Haqqani, a Deobandi seminary that is often referred to as the “University of Jihad.” He has also been a member of the Taliban’s supreme council and head of the religious committee, “which acts as a judiciary branch of the Taliban.”

Ex-Guantanamo detainees hold senior positions within the Taliban’s Islamic Emirate

In May 2014, the Obama administration agreed to exchange five Guantánamo detainees for Bowe Bergdahl, an American soldier who was captured and held by the Haqqani Network after deserting his post. The Taliban continued to tout the exchange as a key “achievement” long after the fact.

President Obama’s own Guantanamo Review Task Force had previously assessed that all five Taliban leaders should be held pursuant to the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), as it was too risky to transfer them.

All five men now hold key positions in the Taliban’s regime. Four of them were appointed to senior posts in the Taliban’s hierarchy, while the fifth was reportedly named the governor of Khost province.

Intelligence cited by U.N. Security Council and Joint Task Force – Guantanamo (JTF-GTMO), which oversees the detention facility in Cuba, ties all five Taliban figures to al Qaeda prior to 9/11. JTF-GTMO assessed that each of the five men was a “high” risk detainee, and “likely to pose a threat to the U.S., its interests, and allies.” At least four of the five were sanctioned by the U.N. in early 2001. The biographical information below comes from the U.N. Security Council’s sanctions pages, leaked JTF-GTMO threat assessments, or other identified sources.

Abdul Haq Wasiq is the acting director of intelligence. Wasiq was the deputy minister of security (intelligence) during the Taliban’s first regime. He was sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council in Jan. 2001.

The U.N. reported that Wasiq was a “local commander” in Nimroz and Kandahar provinces before being promoted to deputy director general of intelligence prior to 9/11. In that capacity, according to the U.N., Wasiq “was in charge of handling relations with al Qaeda-related foreign fighters and their training camps in Afghanistan.”

Wasiq’s al Qaeda ties were also documented by JTF-GTMO’s analysts. U.S. military-intelligence officials found that Wasiq “utilized his office to support al Qaeda and to assist Taliban personnel elude capture” in late 2001. Wasiq also “arranged for al Qaeda personnel to train Taliban intelligence staff in intelligence methods.”

Mohammad Fazl is the deputy defense minister. Fazl had the same role, or a similar one, in the Taliban’s first regime. He was sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council in Feb. 2001. At the time, Fazl was the Taliban’s deputy chief of army staff.

Fazl was a “close associate” of Mullah Omar and “helped him to establish the Taliban government.” The U.N. found that Fazl “was at the Al-Farouq training camp established by al Qaeda.” Fazl “had knowledge that the Taliban provided assistance to the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan…in the form of financial, weapons and logistical support in exchange for providing the Taliban with soldiers.” The IMU worked closely with al Qaeda at the time. Fazl also commanded a fighting force “of approximately 3,000 Taliban front-line troops in the Takhar Province in October 2001.”

According to JTF-GTMO, Fazl had “operational associations with significant al Qaeda and other extremist personnel.” Fazl allegedly conspired with Abdul al-Iraqi, one of Osama bin Laden’s chief lieutenants and the head of al Qaeda’s Arab 055 Brigade, to “coordinate an attack” on the Northern Alliance following the assassination of Ahmad Shah Massoud in Sept. 2001.

Khairullah Khairkhwa is the acting minister for information and culture. Khairkhwa was sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council in Jan. 2001. At the time, he was the Taliban’s governor for Herat Province. He had also served as the governor Kabul province, the minister of internal affairs, and spokesperson during the Taliban’s first regime.

According to JTF-GTMO, Khairkhwa was a close confidante of Mullah Omar prior to 9/11. JTF-GTMO also cited intelligence linking Khairkhwa to Osama bin Laden and Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s camps in Herat. In June 2011, a Washington D.C. district court denied Khairkhwa’s petition for a writ of habeas corpus, based in large part on his admitted role in brokering a post-9/11 deal with the Iranian government. As a result of the talks mediated by Khairkhwa, the Iranians agreed to support the Taliban’s jihad against the U.S. in Afghanistan.

Noorullah Noori is the acting minister of borders and tribal affairs. Noori was sanctioned by the U.N. Security Council in Jan. 2001. At the time, he was both the Taliban’s governor of the Balkh Province, as well as the “Head of the Northern Zone of the Taliban regime.”

According to JTF-GTMO, Noori was a “senior Taliban military commander” prior to his detention. Noori allegedly “fought alongside al Qaeda as a Taliban military general, against the Northern Alliance” and also “hosted al Qaeda commanders.” Along with Mohammad Fazl (below), Noori was suspected of committing “war crimes,” “including the murder of thousands of Shiite Muslims” prior to the U.S.-led invasion in 2001.

Mohammad Nabi Omari wasn’t named to the senior staff of the Taliban’s regime, but he was reportedly appointed the new governor of Khost province. He has longstanding ties to the Haqqani Network and attended talks in Doha on its behalf.

Prior to this time in U.S. custody, according to JTF-GTMO, Omari “was a senior Taliban official who served in multiple leadership roles.” Omari was allegedly a “member of a joint al Qaeda/Taliban” cell in Khost “and was involved in attacks against U.S. and Coalition forces.” He was also a “close associate” of Jalaluddin Haqqani and worked with the Haqqani Network.

Omari’s son, Abdul Haq, was killed during fighting in Khost province in July. Like his father, Abdul Haq reportedly fought for the Haqqani Network. The Taliban celebrated Abdul Haq’s “martyrdom” in a statement on Voice of Jihad, noting that the group’s leaders, including Akhundzada, were willing to lose their sons in their campaign to conquer Afghanistan. The Taliban had a point.