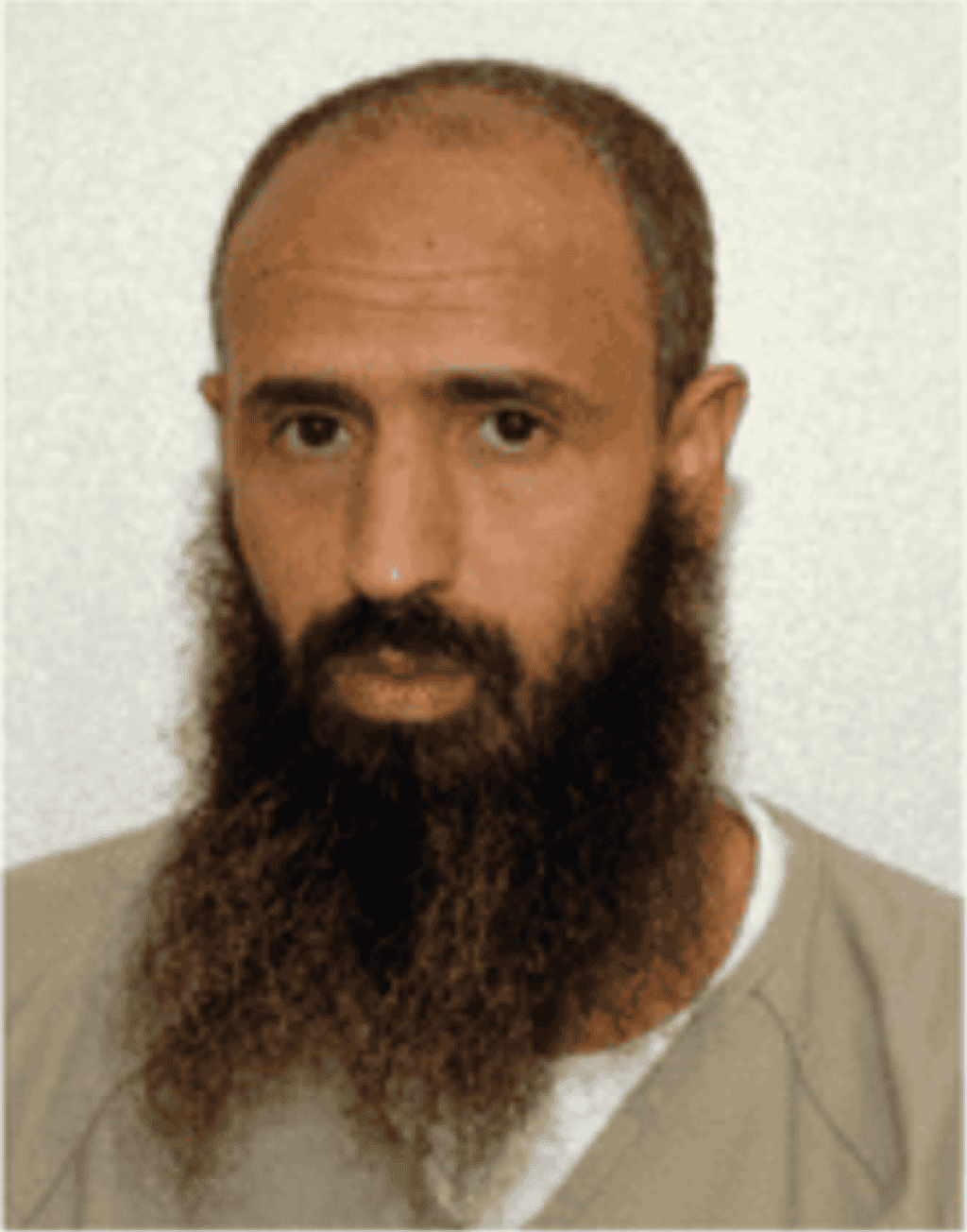

The U.S. State Department announced on July 19 that Abdul Latif Nasir, a detainee held at Guantanamo since 2002, had been transferred to his native country of Morocco. Nasir’s transfer from Guantánamo is the first during the Biden-Harris administration, which seeks to close the facility.

According to an unclassified summary prepared for Nasir’s case, U.S. officials found that he had “fought for several years with the Taliban on the front lines in Kabul and Bagram, Afghanistan, and again at Tora Bora,” where he served “as a commander and weapons trainer.” Nasir’s relationship with Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda began in the mid-1990s in Sudan. He allegedly worked his way up within the organization to become a “member of the al Qaeda training subcommittee.”

In Oct. 2008, analysts working for Joint Task Force – Guantánamo (JTF-GTMO) assessed Nasir to be a “high risk” who is “likely to pose a threat to the US, its interests, and allies.” JTF-GTMO recommended that Nasir be held in “continued detention.” By that point in time, most of the detainee population had already been transferred or released by the Bush administration.

President Obama sought to shutter the Guantánamo detention facility shortly after his inauguration in Jan. 2009. The Obama administration established a task force to review the intelligence and evidence gathered on the 240 detainees remaining there. The Obama task force determined that 48 of those detainees were “too dangerous to transfer but not feasible for prosecution.”

Nasir was one of those 48 detainees. Per the task force’s recommendation, he was held “pursuant to the government’s authority under the Authorization for Use of Military Force passed by Congress in response to the attacks of September 11, 2001.”

Nasir was then given the ability to challenge his continued detention as part of a process overseen by a Periodic Review Board (PRB) established by President Obama in 2011.

PRB approves Nasir for transfer to Morocco

In July 2016, the PRB approved Nasir’s transfer out of Guantánamo, but only to his native Morocco and so long as “appropriate security assurances” were negotiated by U.S. officials. The Trump administration then declined to follow through on his transfer.

The PRB found in 2016 that Nasir “presents some level of threat in light of his past activities, skills, and associations,” but the “threat [he] presents can be adequately mitigated” by the “factors and conditions” of his transfer.

Nasir’s testimony before the PRB hasn’t been released to the public. But the PRB praised his “candid responses” to questions “regarding his reasons for going to Afghanistan and activities while there.”

The PRB went on to cite Nasir’s “well-established family,” “renunciation of violence,” “low number of disciplinary infractions while in detention,” and efforts to “educate himself” while detained as reasons to support his transfer. Nasir’s advocates say he can work for his brother’s successful business in Morocco.

An alleged fundamentalist in high school and college

According to the biography presented by U.S. officials to the PRB, Nasir was a member of a “conservative,” “non-violent but illegal” group in Morocco named Jamaat al Adi wa al-Ihassan. Nasir joined the group in the 1980s.

JTF-GTMO’s threat assessment cites Nasir’s own “account of events,” dating back to his early life in Morocco.

Summarizing Nasir’s account, JTF-GTMO’s analysts wrote that he was an “active member of the Islamic fundamentalist group,” Jamaat al Adi wa al-Ihassan, “throughout high school and college.” That same organization seeks “to replace the Moroccan monarchy with an Islamic state and uses education to get people to support its position.”

When the Moroccan government cracked down on the organization “in the summer of 1990,” Nasir fled to Tripoli and Benghazi, Libya, where his brother was living at the time. Nasir also visited Sudan and eventually relocated there in the summer of 1993.

Met Osama bin Laden in the mid-1990s

Nasir told officials that he joined Jamaat Tablighi, a proselytizing group, in Sudan and studied the Koran. But he also “secured a job” with Wadi al-Aqiq, a company owned by Osama bin Laden. Nasir worked as a “supervisor for a charcoal production unit” of that company.

Nasir “first met” Osama bin Laden in 1995 when the al Qaeda founder “was inspecting his agricultural operation” in Sudan. Around that time, the JTF-GTMO threat assessment reads, Nasir “began thinking of himself as an extremist fighter.”

During a visit to Khartoum, Nasir encountered a recruiter for the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) known as Abd al-Hakim al-Libi al-Rafil. The LIFG man “indoctrinated and recruited” Nasir “to travel to Chechnya to conduct extremist operations.”

In April 1996, according to the JTF-GTMO summary, Nasir “made a failed attempt to travel to Chechnya via Yemen for extremist activity.” After hearing that Osama bin Laden had relocated from Sudan to Afghanistan that same year, Nasir made the trip himself, apparently traveling via Syria and Pakistan.

Joined the jihad in Afghanistan

According to Nasir’s own summary of events, as told to interrogators and recounted by JTF-GTMO, he first traveled to the Khaldan Training camp, staying at “an LIFG-sponsored guesthouse in Jalalabad” while en route. His stay at Khaldan lasted only a few days, as a “dispute between Algerians and ‘other Arabs’” disrupted operations. Nasir then “transferred and completed his basic training” at al Qaeda’s Al Farouq training camp. While there, Nasir “received basic skills training on the AK-47 assault rifle, map reading, camouflage, artillery, and mountain tactics.”

After completing his basic training, Nasir “joined a group of Arab fighters” in Kabul. Beginning in 1998, Nasir “fought alongside the Taliban against the Northern Alliance on both the Bagram and Kabul lines for the next three years.”

While in custody, Nasir allegedly explained that he fought under an Uzbek known as Juma Biad, who commanded all “non-Afghan fighters in Afghanistan.” JTF-GTMO’s analysts identified “Juma Biad” as Jumaboy Namangani, the “former leader of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan,” or IMU.

Nasir’s “immediate commanders” were identified as “Abd al-Salaam al-Hadrami, aka (Muammar Said Abd al-Dayan) and Omar Sayf,” both of whom “were known commanders in [Osama bin Laden’s] 55th Arab Brigade.” They were also both killed during fighting in 2001. JTF-GTMO assessed Nasir to be a member of that same fighting outfit, the 55th Arab Brigade.

A commander during the Battle of Tora Bora

After Kabul fell to U.S.-led forces in Nov. 2001, Nasir “became the emir” (or leader) of a group of fighters, according to JTF-GTMO. He “met up with” another Libyan, Ali Muhammad Abd al-Aziz al-Fakhri (a.k.a. Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi), the former Khaldan camp commander. Ibn al-Shaykh “ordered” Nasir’s “group to retreat to Jalalabad and on to Tora Bora in mid-November 2001.”

Once in the Tora Bora Mountains, Nasir became a direct “subordinate” to another al Qaeda figure known as Abd al-Qadus, the “former emir of” Al Farouq camp and “overall commander of the front lines.” Nasir had a “GPS unit and four radios, which he used to communicate with his subordinates and manage the battle.”

While in Tora Bora, Nasir “attended at least one meeting with” bin Laden.

Northern Alliance fighters captured Nasir and other jihadists as they attempted to flee into Pakistan in mid-December 2001. JTF-GTMO’s analysts “assessed” that Nasir had been “part of the larger group of al Qaeda fighters led out of Tora Bora by” Ibn al-Shaykh al-Libi.

Nasir stopped cooperating in 2004

Much of the summary above is sourced to the version of events Nasir offered to his interviewers or interrogators at Guantanamo. Multiple footnotes in the JTF-GTMO threat assessment are sourced to his testimony as late as 2003. That same year, Nasir allegedly “admitted” that “previous accounts of his activities in Sudan and Afghanistan were a cover story designed to conceal his association with” Osama bin Laden. That is, Nasir may have intentionally downplayed the extent of his ties to bin Laden.

Nasir stopped cooperating with the Americans by 2004, as he began employing “counter-interrogation techniques.” At one point, Nasir apparently “changed his affiliation from al Qaeda to the Taliban.”

Nasir “admitted, retracted, and reasserted his claim to have personally met with” Osama bin Laden on “multiple occasions.” The JTF-GTMO file cites meetings between the two: at the wedding of Osama bin Laden’s son, a funeral for an al Qaeda fighter, in Sudan, and at Tora Bora.

The JTF-GTMO threat assessment notes that Nasir’s “participation” in the Feb. 2001 wedding of bin Laden’s son, Muhammad, to the daughter of Abu Hafs al-Masri (a senior al Qaeda commander) was “corroborated” by another former Guantanamo detainee, Mohamedou Ould Salahi. (The footnote to Salahi’s statement seems to be dated sometime in 2004.) Salahi’s own time in U.S. custody was controversial because he was subjected to torture techniques.

JTF-GTMO’s analysts found that, before he stopped to speaking to interrogators, Nasir had “admitted being an explosives trainer and a member of the al Qaeda explosives committee.” Other detainees identified Nasir as an explosives expert, or said he had received advanced explosives training, as well. One of them is a “senior al Qaeda lieutenant,” Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn, a.k.a. Abu Zubaydah. Abu Zubaydah “photo-identified” Nasir as a “Moroccan and an al Qaeda explosives expert” known as “Abu Talha al Moroc.” Abu Zubaydah also said that Nasir was a “member of the Training Subcommittee of the Military Committee in the al Qaeda organizational structure.” (The summary provided by U.S. officials to the PRB in 2016 reiterated this claim — that is, Nasir was “a member of the al Qaeda training subcommittee.”)

Like Salahi, Abu Zubaydah’s time in U.S. custody became controversial, as he was subjected to waterboarding and other torture techniques.

Some of the other details cited in the file are sourced to a single detainee, such as one claim that Nasir was personally involved in helping the Taliban blow up statutes of the Buddha in 1999.

Still, a number of captured al Qaeda operatives identified Nasir as an important figure. For example, Nasir’s “activities as an al Qaeda battlefield commander” were “corroborated in detail by multiple independent sources.”

Recovered al Qaeda files and media

In addition to accounts provided by Nasir’s fellow detainees, JTFO-GTMO’s analysts cited recovered al Qaeda documents and media that seemingly referred to Nasir. One of the documents is a “list of al Qaeda members” in Afghanistan that was found in the “home of deceased senior al Qaeda commander Abu Hafs al Masri” in December 2001. JTF-GTMO concluded that the “Abu al-Harith” mentioned in the document was an alias used by Nasir.

Nasir’s name was also “recovered from documents and electronic media” found during the Sept. 11, 2002, raid on an al Qaeda safe house in Karachi, Pakistan. That same safe house was “controlled” by 9/11 conspirator Ramzi Bin al-Shibh, who was captured during the raid and is still held at Guantánamo.

One of the documents captured during the Karachi raid is titled “Very Private.doc.” It allegedly lists Nasir under an alias and explains that $1,500 was taken from his account and “placed into the al Qaeda budget under direct orders of senior al Qaeda commander” Saif al Adel. Today, al Adel is thought to be the deputy leader of al Qaeda’s international operation.

According to JTF-GTMO’s threat assessment, Nasir told his captors that the U.S. missed an opportunity to kill or capture Osama bin Laden in the Tora Bora Mountains in late 2001.

Nearly twenty years, Nasir has been transferred to his home country.