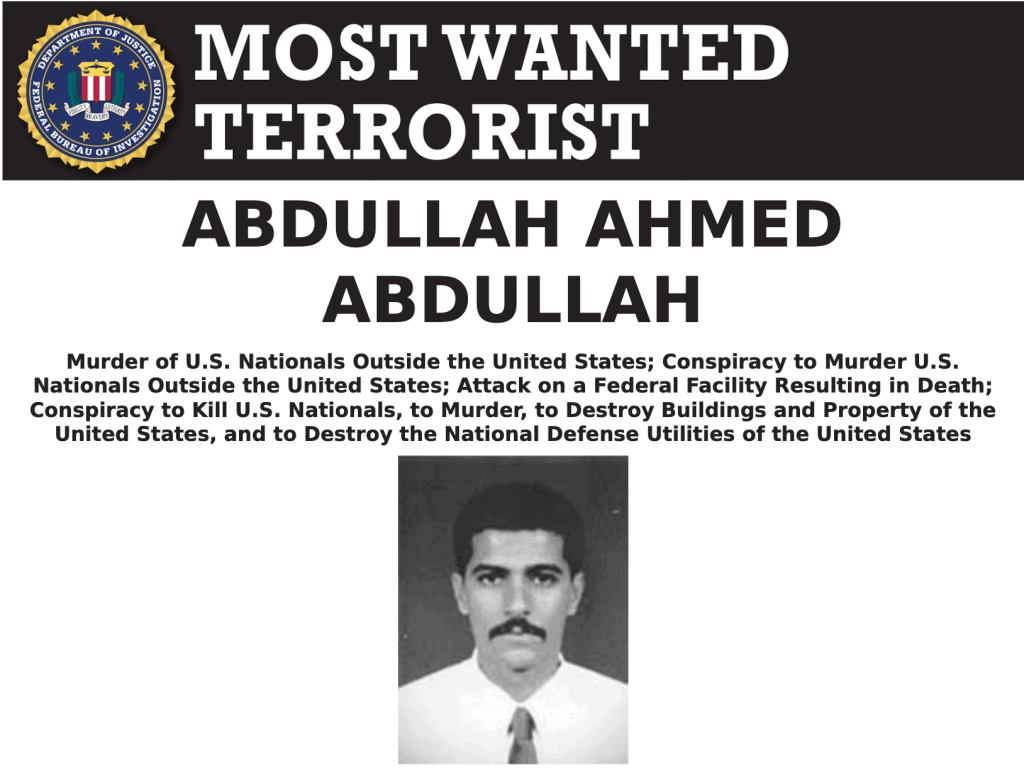

Last month, an al Qaeda-linked social media account reported that Abu Muhammad al-Masri (a.k.a. Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah) had been killed under mysterious circumstances inside Iran. The New York Times and other press outlets, citing anonymous intelligence officials, have now confirmed that the al Qaeda leader was in fact assassinated by Israeli operatives at the behest of American officials.

The Times reports that al-Masri was “gunned down on the streets of Tehran by two assassins on a motorcycle on Aug. 7,” the anniversary of al Qaeda’s 1998 U.S. embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania. Those twin bombings, which left 224 people dead, were al Qaeda’s most devastating attacks prior to the 9/11 hijackings. Al-Masri had been wanted for his alleged role.

Citing “American intelligence officials,” the Times reports that al-Masri had been “living freely in the Pasdaran district of Tehran, an upscale suburb, since at least 2015.”

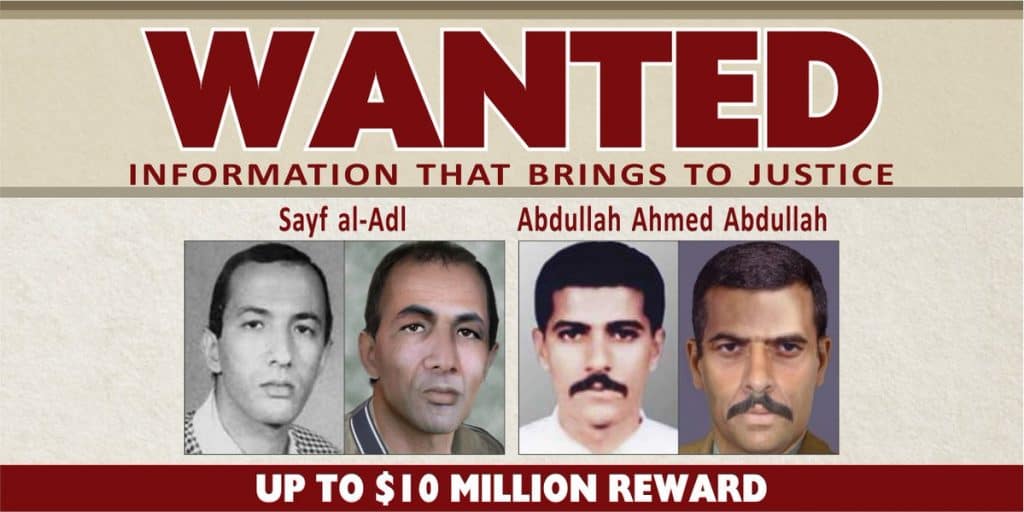

Alongside four of his al Qaeda comrades, Al-Masri was freed from some form of Iranian detention in 2015. Al Qaeda reportedly kidnapped an Iranian diplomat in order to force the exchange. Three of the freed veteran jihadists then relocated to Syria, where they were killed. The sole survivor of that cadre is now Saif al-Adel — another al Qaeda veteran who is in the group’s line of succession and lives in Iran.

Abu Muhammad al-Masri was reportedly killed alongside his daughter, Miriam, who was the widow of Hamza bin Laden. In 2017, FDD’s Long War Journal helped convince the U.S. government to release their wedding video, along with thousands of other files recovered in Osama bin Laden’s compound. Their wedding took place inside Iran, where Hamza lived for years, sometimes under contentious circumstances, after fleeing Afghanistan in 2001. Hamza was killed in a separate U.S. counterterrorism operation.

The complex relationship between the Iranian government and al Qaeda, who have been at odds in various ways, is often misunderstood. In the report below, which draws on previous writings, FDD’s Long War Journal provides additional context for this story.

Abu Muhammad’s death was first reported on jihadist social media.

Abu Muhammad’s death was initially reported by an al Qaeda-linked social media account on Rocket.Chat. Before the current round of reporting, MEMRI first summarized that account of his death, which was shared by a user known as @awrakmuhajir and authored by someone known as “Jassim.”

In Jassim’s telling, Iran’s Fars News Agency and other Iranian outlets provided contradictory details concerning what transpired. The Iranian press claimed that the father and daughter killed were in fact Lebanese nationals known as Habib and Mariam (Miriam) Dawoodi. Habib was even reported to be a member of Hezbollah. However, this was a misdirection, a cover story that was intended to cover up the presence of such a high-ranking al Qaeda figure.

As reported by MEMRI, Jassim also accused al Qaeda’s leadership of trying to bury the news, so as to avoid embarrassing Iranians officials, who are harboring other members of the group. Jassim worried about the effect of Abu Muhammad’s demise on al Qaeda’s hierarchy.

This story demonstrates, once again, the value of monitoring jihadi discourse and social media. While some of what is reported by such sources is inaccurate, or grossly exaggerated, they often do provide valuable insights. The secretive operation to kill Abu Muhammad is a case in point. It wasn’t reported by the Israeli or U.S. governments, nor the Iranians, nor by al Qaeda’s official media apparatus. Instead, it was leaked on an al Qaeda-linked social media account by a user who was clearly concerned about the ramifications. More than three weeks later, the jihadist’s version of the story was confirmed by intelligence officials who spoke to The New York Times and then other press outlets.

Why was al-Masri killed on the anniversary of the Aug. 7, 1998, U.S. embassy bombings?

It is no accident that Abu Muhammad al-Masri was targeted on Aug. 7. It was likely intended to send a message — a form of symbolic payback.

As FDD’s Long War Journal has documented on multiple occasions, the U.S. government has repeatedly assessed, based on the testimony of al Qaeda participants and other evidence, that the Aug. 7, 1998, U.S. embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania were modeled after the near-simultaneous attacks in 1983 on the Marine and French barracks in Lebanon. The latter bombings were conducted by Iran’s terror proxies.

The 9/11 Commission documented this key link in its final report. Discussions between al Qaeda and Iran in the early 1990s were brokered by Hassan al-Turabi, who was then a prominent Islamist in Sudan’s government. Al Qaeda was based in Sudan at the time and Turabi’s country functioned much like the Mos Eisley Cantina in the original Star Wars, housing various bad actors looking to cut deals with one another. Turabi advocated big tent jihadism when it came to confronting the U.S. and the West. Turabi was even nicknamed the “Pope of Terrorism” for his ecumenical approach. Consistent with his vision of a grand anti-Western alliance, Turabi “sought to persuade Shiites and Sunnis to put aside their divisions and join against the common enemy,” according to the 9/11 Commission.

The discussions between “al Qaeda and Iranian operatives led to an informal agreement to cooperate in providing support – even if only training – for actions carried out primarily against Israel and the United States,” the 9/11 Commission found. “Not long afterward, senior al Qaeda operatives and trainers traveled to Iran to receive training in explosives.” During the “fall of 1993, another such delegation went to the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon for further training in explosives as well as in intelligence and security.” The Bekaa Valley has long been a Hezbollah stronghold.

The trainers taught al Qaeda operatives how to carry out suicide bombings such as those orchestrated by Hezbollah in Lebanon. The 9/11 Commission wrote that Bin Laden “reportedly showed particular interest in learning how to use truck bombs such as the one that had killed 241 U.S. Marines in Lebanon in 1983.”

Federal prosecutors in the Clinton administration discovered Iran’s and Hezbollah’s training of al Qaeda operatives. They included the relationship in their indictment of al Qaeda in 1998, noting that bin Laden and his men had “forged alliances” with the Sudanese regime, as well as “the government of Iran and its associated terrorist group Hezbollah for the purpose of working together against their perceived common enemies in the West, particularly the United States.”

More details concerning Iran’s and Hezbollah’s assistance came to light during the trial of some of the al Qaeda operatives responsible for the 1998 U.S. embassy bombings.

In his plea hearing before a New York court in 2000, Ali Mohamed – an al Qaeda operative who was responsible for performing surveillance used in the bombings – testified that he had set up the security for a meeting between bin Laden and Mugniyah. “I arranged security for a meeting in the Sudan between Mugniyah, Hezbollah’s chief, and bin Laden,” Mohamed told the court.

Mohamed also confirmed that Hezbollah and Iran had provided explosives training to al Qaeda. “Hezbollah provided explosives training for al Qaeda and [Egyptian Islamic] Jihad,” Mohamed explained. “Iran supplied Egyptian Jihad with weapons.” Mohamed was originally a member of Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ), an organization that merged with bin Laden’s enterprise and closely cooperated with the al Qaeda founder’s men well before the formal merger. (Abu Muhammad al-Masri and Saif al-Adel were EIJ men as well.)

Mohamed explained al Qaeda’s rationale for seeking assistance from Iran and Hezbollah:

And the objective of all this, just to attack any Western target in the Middle East, to force the government of the Western countries just to pull out from the Middle East…Based on the Marine explosion in Beirut in 1984 [sic: 1983] and the American pull-out from Beirut, they will be the same method, to force the United States to pull out from Saudi Arabia.

Jamal al Fadl, an operative who was privy to some of al Qaeda’s most sensitive secrets, conversed with his fellow al Qaeda members about Iran’s and Hezbollah’s explosives training, which included take-home videotapes so that al Qaeda’s terrorists would not forget what they learned. “I saw one of the tapes, and he [another al Qaeda operative] tell me they train about how to explosives big buildings,” Al Fadl told federal prosecutors.

One of the al Qaeda leaders who attended the training was Saif al Adel, Abu Muhammad al-Masri’s longtime comrade. Al Adel fled to Iran after the 9/11 hijackings and was tied to operations elsewhere, including inside Saudi Arabia. His status was murky for years, but he was among the al Qaeda leaders freed by the Iranians from some form of detention in 2015.

Although many assume that Iran and al Qaeda couldn’t cooperate because of their ideological differences, the 9/11 Commission concluded “that Sunni-Shia divisions did not necessarily pose an insurmountable barrier to cooperation in terrorist operations.”

U.S. intelligence officials have been tracking senior al Qaeda leadership in Iran.

Nearly three decades after al Qaeda’s men received the aforementioned training in Iran and Lebanon, American officials continued to track some them inside Iran. U.S. officials have repeatedly pointed to a cadre of al Qaeda leaders inside Iran.

On Aug. 8, 2018, the U.S. State Department announced that it increased its reward for information concerning the whereabouts of al-Masri and al-Adel. Despite doubling the reward offer from $5 million to $10 million for each al Qaeda veteran, Foggy bottom didn’t indicate that the two were located inside Iran. Still, their whereabouts was well-known.

A contemporaneous report authored by a team of experts working for the United Nations Security Council indicated that al-Masri and al-Adel were weighing in on the jihadist controversies in Syria.

“Al Qaeda leaders in the Islamic Republic of Iran have grown more prominent, working with” Ayman al-Zawahiri and “projecting his authority more effectively than he could previously,” the UN report, authored in mid-2018, reads. Specifically, the pair worked to undermine the authority of Abu Muhammad al-Jawlani, the head of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). They encouraged the formation or re-establishment of other jihadist groups to act as counterweights to HTS, which has been at the center of heated disagreements within jihadist circles since its establishment in early 2017.

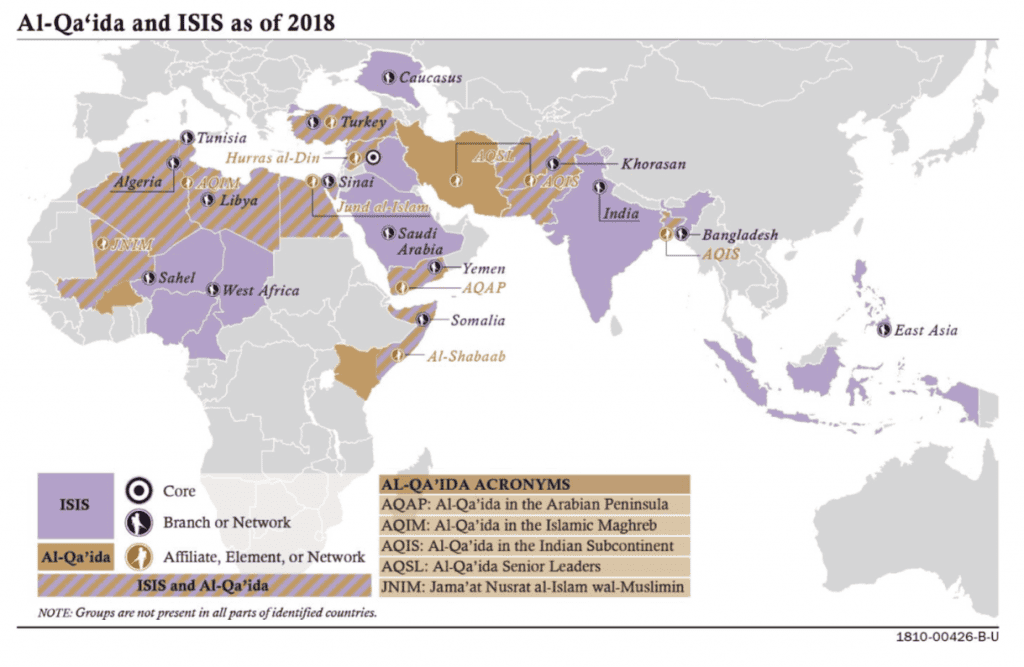

In January 2019, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) released a map (seen below) of the global networks maintained by al Qaeda and ISIS. There are some conceptual problems with the map, which may make it seem like these groups are stronger in certain areas than they really are. Regardless, the map points to the presence of “AQSL” (Al Qaeda Senior Leaders) in Iran — another indication that U.S. intelligence is keenly aware that some of the organization’s most significant personnel are located inside the Shiite-dominated nation.

On Sept. 17, Christopher Miller, who was then the director of the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) and is now the acting Secretary of Defense, told Congress that “several” of al Qaeda’s “remaining senior leaders continue to find safe haven in Iran, and will likely play a key role in the group’s efforts to reconstitute its leadership.” Miller believes that the U.S. and its allies are on the “verge of defeating” al Qaeda, an argument he has made in the context of the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. And he has flubbed some basic details with respect to al Qaeda’s leadership hierarchy. Still, the NCTC finds the presence of al Qaeda honchos inside Iran to be significant.

In addition to keeping tabs on senior al Qaeda figures inside Iran, the U.S. Treasury and State Departments have repeatedly exposed Iran’s formerly “secret deal” with the Sunni jihadists. Under an agreement with the regime, al Qaeda has maintained its “core facilitation pipeline” inside Iran. Curiously, the Iranians have allowed this facilitation network to operate even though Iran and al Qaeda are on opposite sides of the conflicts in Syria and Yemen.

Now deceased al Qaeda operative confirmed al-Masri and al-Adel were living “their natural lives” in Iran.

A well-placed al Qaeda source who was involved in the disputes over HTS in Syria also confirmed that al-Masri and al-Adel were operating inside Iran.

Abu al-Qassam al-Urduni (also known as Khalid Aruri and Abu Ashraf) had once been held inside Iran. But he was one of the al Qaeda leaders, alongside al-Masri and al-Adel, released in exchange for an Iranian diplomat in 2015.

After an HTS official claimed that al-Masri and al-Adel lacked the authority to weigh in on HTS’s legitimacy, because they were supposedly detained inside Iran, al-Urduni countered by explaining that al-Masri and al-Adel “left prison and they are not imprisoned.” The two al Qaeda managers “are forbidden from traveling until Allah makes for them an exit,” al-Urduni wrote, but “they move around and live their natural lives except for being allowed to travel.”

In June, Abu al-Qassam al-Urduni was targeted in an apparent U.S. drone strike with a R9X missile — an exotic, blade-wielding weapon that is intended to reduce collateral casualties. His death was one in a series of targeted killings this year.

Indeed, three of the five al Qaeda veterans released by the Iranians in 2015 have been killed in Syria. In addition to Abu al-Qassam al-Urduni, Abu Khallad al-Muhandis (also known as Sari Shihab) was killed in an explosion in Idlib in Aug. 2019 and Abu al-Khayr al-Masri perished in a Feb. 2017 drone strike in Idlib. At the time of his death, Abu al-Khayr al-Masri was one of Zawahiri’s top deputies. Months earlier, Abu al-Khayr had personally approved Al Nusrah Front’s public “disassociation” from al Qaeda, a move that eventually led to the establishment of HTS and the bitter jihadist infighting in Idlib.

Leaked documents show Abu Muhammad al-Masri was in al Qaeda’s line of succession.

The jihadists’ bickering in Idlib has led to other revelations concerning al Qaeda’s inner workings. As result of the infighting in late 2018 and early 2019, an HTS official known as Abu ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Zubayr al-Ghazi shared handwritten documents signed by six members of al Qaeda’s shura council. The documents were old, as they had been authored sometime before mid-2015. And some of the authors were subsequently killed.

But the documents set forth how al Qaeda’s oath of allegiance (or bayat) and line of succession worked at one point in time.

All of the signatories agreed that they would renew their oaths of fealty to al Qaeda in the event that Ayman al-Zawahiri (long rumored to be in poor health) was killed or otherwise incapacitated. All six authors specified that they would pledge allegiance to Abu al-Khayr al-Masri (killed in a U.S. drone strike in Idlib in Feb. 2017), followed by Abu Muhammad al-Masri (killed in an Israeli operation on Aug. 7, 2020), Saif al-Adel, and then Nasir al-Wuhayshi (who was killed in a June 2015 drone strike in Yemen, but served as the emir of AQAP and a senior manager within al Qaeda’s global organization). The oaths stipulated that each al Qaeda leader be physically located in the Khorasan (Afghanistan, Pakistan or possibly parts of the surrounding countries), or in one of al Qaeda’s regional branches. The signatories agreed to move down the chain-of-command until one of Zawahiri’s deputies was appropriately situated to accept his oath.

After the killing of Abu Muhammad al-Masri on Aug. 7, only one of the four al Qaeda leaders mentioned in those documents remains alive: Saif al-Adel. He, too, has been living in Iran.

FDD’s Long War Journal cautions that even though these senior figures have been killed, it is likely that al Qaeda has updated its line of succession. It is easy to point to other al Qaeda veterans who could have taken their place. Still, the leadership losses have an effect and undoubtedly weaken the group’s infrastructure and hierarchy.