On May 19, the Lead Inspector General (IG) for Operation Freedom’s Sentinel released its quarterly report. The assessment covers recent events in the Afghan War, including the Feb. 29 withdrawal agreement between the U.S. and Taliban. Several parts of the report are summarized below.

The Taliban’s leaders are “reluctant to publicly break with al Qaeda.”

State Department officials, including Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Special Representative Zalmay Khalilzad, have endorsed the Taliban’s supposed counterterrorism assurances as part of the withdrawal accord. To date, however, there is no public indication of a “break” between the Taliban and al-Qaeda.

The State Department told the IG that “implementation of the U.S.-Taliban agreement will require extensive long-term monitoring to ensure Taliban

compliance as the group’s leadership has been reluctant to publicly break with al Qaeda.”

Left unsaid is how the Taliban could privately break with al Qaeda, without it becoming public. Al Qaeda’s men would surely complain if its longtime blood brothers in the Taliban suddenly turned on them. There would be some outward indication of a break. There are at least several hundred al Qaeda fighters embedded within the Taliban-led insurgency, according to a United Nations monitoring team. Other al Qaeda-affiliated groups, including the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP), are fighting to resurrect the Taliban’s Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan as well.

The State Department’s assessment points to fundamental questions: If the Taliban isn’t willing to “publicly break” with al-Qaeda, then why should Americans believe any of the group’s counterterrorism assurances? And if there is nothing to the Taliban-al Qaeda relationship, as some insist, then why wouldn’t the Taliban issue a formal renunciation of al Qaeda as part of a deal with the U.S.?

The Taliban’s “reluctance” in this regard is telling.

The IG cites additional reasons for skepticism. The Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) cited “open-source reporting” indicating that while Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) “was concerned about the peace talks,” it “continued to maintain a close relationship with the Taliban.” There’s no evidence of a break between the Taliban and AQIS.

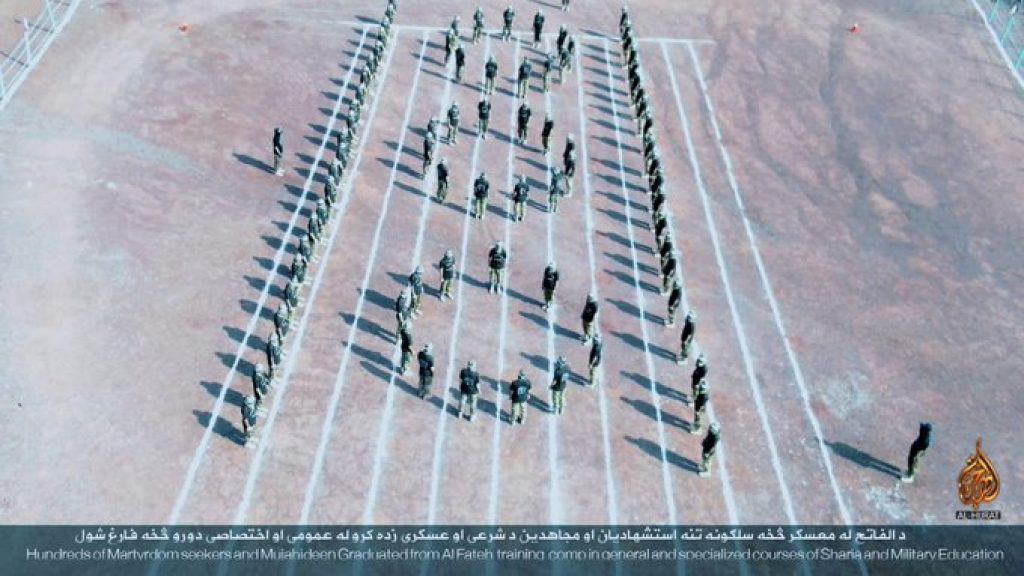

Al Qaeda’s senior leadership has also lauded the deal. The IG cites an analysis by FDD’s Long War Journal of a three-page statement issued by al Qaeda’s general command. Al Qaeda praised the Feb. 29 accord as a “great victory” and encouraged people to “join the training camps under the leadership of the Islamic Emirate.” There’s no hint of concern in the statement. The IG also cites a January report by a UN monitoring team, which concluded that the Taliban and al Qaeda continue to enjoy a “mutually beneficial” relationship.

In addition, the IG points to an op-ed attributed to Sirajuddin Haqqani that was published by the New York Times on Feb. 20, 2020. Haqqani is the deputy emir of the Taliban’s Islamic Emirate. His network has been closely allied with al Qaeda since the 1980s. The author of the op-ed mentioned “disruptive groups,” claiming that they are the subject of “politically motivated exaggerations” by “warmongers.” At no point did the author mention al Qaeda, let along renounce the group or his longstanding relationship with it. And although the IG indicates that the “disruptive groups” include al Qaeda and others, “Haqqani” could just as easily have had the Islamic State’s Khorasan province (ISIS-K), which opposes the Taliban, in mind. The IG reminds readers that, according to the FBI, Haqqani “maintains close ties to al Qaeda.” Indeed, Haqqani does and there is no indication in the Times op-ed or elsewhere that this alliance has changed.

Both Haqqani and Haibatullah Akhundzada, the Taliban’s “Emir of the Faithful,” have been “reluctant” to publicly disavow al Qaeda.

Given that the U.S. pledged to withdraw all foreign forces from Afghanistan within 14 months of the deal being signed, it isn’t clear how the U.S. can ensure “long-term monitoring.” The U.S. has struggled to keep track of al Qaeda even with thousands of service members in country.

There are no verification or enforcement mechanisms specified in the terse, publicly-available text of the agreement. The State Department told the IG that the “details regarding the implementation arrangements for the agreement are classified and will be reported on in a future report’s classified appendix.”

The Taliban went on the offensive after the Feb. 29 agreement with U.S.

The U.S. and the Taliban agreed to a week-long “reduction in violence” leading up to the signing of the Feb. 29 withdrawal deal in Doha. Even though U.S. officials trumpeted this reduction period, the IG’s office found that “Taliban violence continued at high levels” during that same week. Although the Taliban “limited violence against coalition forces,” the group “increased attacks against the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) during this period.” However, Afghan officials themselves said that “violence was down about 80 percent nationwide during the 7-day agreement.”

There is no ambiguity concerning what followed the Feb. 29 deal.

“[A]lmost immediately after signing this agreement” in Doha, the Taliban “ramped up attacks against the ANDSF.” The jihadists “declared that ANDSF forces were not off-limits, and Taliban levels of violence escalated throughout Afghanistan, raising questions as to the future of the agreement.”

Citing “media sources,” the IG reports that the Taliban “launched more than 300 attacks, with major assaults in several provinces” and the “insurgents seizing territory and inflicting heavy ANDSF casualties” during the last two weeks of the quarter — meaning the second half of March.

On Mar. 22, the Taliban assaulted “ANDSF checkpoints and bases in Zabul province, killing 37” people. Three Taliban offensives were launched around Mar. 28 in the provinces of Kunduz, Faryab and Badakhshan.

The Taliban has consistently rejected calls for a ceasefire. Although its senior leaders have demonstrated an ability to control operations throughout the country, they have refused to rein in their insurgents.

U.S. officials have called on the Taliban to reduce violence, saying the current scale of the fighting may “jeopardize” the deal. But the U.S. continued to move forward with its troop withdrawals even as the Taliban escalated its operations against the ANDSF. The U.S. also continued to bomb Taliban positions in defense of the ANDSF.

More than two months after the deal was signed, President Ashraf Ghani announced that Afghan forces would no longer remain on the defensive and would resume offensive operations.

U.S. military suppresses information on “enemy-initiated” attacks and airstrikes .

The quarterly IG reports usually contain data on “enemy-initiated” attacks, a metric that defense officials have previously used to assess (sometimes inaccurately) progress in the war. However, the most recent report doesn’t include such data.

According to Acting Inspector General Sean W. O’Donnell, although such data are “normally discussed in Lead IG reports,” the Department of Defense (DoD) deemed the information “sensitive as it was part of ongoing interagency deliberations over whether the Taliban is complying with the terms of the agreement with the United States.”

The DoD’s argument is curious, to say the least. There is nothing in the written accord limiting Taliban attacks on the ANDSF. Publicly-available information, including reports cited by the IG, confirms that the Taliban went on the offensive after Feb. 29. The UN also separately maintains data on civilian casualties. The UN’s reporting shows that the Taliban is still the main driver of war in Afghanistan and there was a “disturbing increase in violence” following the deal. And any attacks on coalition forces during the withdrawal would be noticeable. Therefore, it isn’t clear why suppressing information about actions that are plain to see is somehow necessary for “interagency deliberations.”

The DoD did state “that once the deliberations are complete, the attack data can be released to the public.”

The U.S. military also refused to provide the IG with data on airstrikes for March. The IG’s office reports that there were 417 airstrikes in January and 228 in February, but U.S. Forces – Afghanistan “would not release the March airstrike data due to the sensitivity of ongoing deliberations over the Taliban’s compliance with the February 29 agreement.” Again, it isn’t clear why suppressing data on American airstrikes is necessary, given that the Taliban’s post-deal offensive is obvious.

In addition to the data on “enemy-initiated attacks” and American airstrikes, the U.S. military previously withheld data on district-level stability, even though that was once considered a key metric of success.

Pakistan continues to harbor Taliban senior leadership, including Haqqanis.

The DIA reported to the IG’s office that Pakistan “has encouraged the Afghan Taliban to participate in peace talks, but refrained from applying coercive pressure that would seriously threaten its relationship with the Afghan Taliban to dissuade the group from conducting further violence.”

The DIA also relayed that “Pakistan continues to harbor the Taliban and associated militant groups in Pakistan, such as the Haqqani Network,

which maintains the ability to conduct attacks against Afghan interests.”

Again, the Haqqani Network remains allied with al Qaeda.

ISIS-K remains a threat in Afghanistan, despite setbacks and loss of territory in Nangarhar.

The IG reports that “sustained military pressure” from the U.S. and ANDSF, “as well as from the Taliban, appear to have taken a heavy toll on the” Islamic State’s so-called Khorasan province (ISIS-K).

The DIA “assessed that as of mid-March” ISIS-K had “approximately 300 to 2,500” members in Afghanistan, and “only 50 to 100” members in Nangarhar province. But the wide range in estimated personnel doesn’t inspire confidence. As FDD’s Long War Journal has repeatedly reported, it is unlikely that the U.S. knows how many ISIS members there are in Afghanistan or elsewhere.

ISIS-K has conducted “high-profile” attacks in Kabul this year and retains cells in Kabul and likely other provinces.