Shortly after the Trump administration signed its accord with the Taliban on Feb. 29, Taliban leader Haibatullah Akhundzada declared “victory” on behalf “of the entire Muslim and Mujahid nation.” It’s easy to see why.

The State Department agreed to a lopsided deal in which the Taliban extracted several significant concessions in exchange for little. The U.S. agreed to a full withdrawal from Afghanistan within 14 months, the delisting of Taliban leaders from international sanctions lists, and an uneven prisoner exchange that would free 5,000 jihadists for just 1,000 prisoners held by the Taliban. (The Afghan government quickly balked at this concession.) The Taliban has agreed to take part in intra-Afghan negotiations, but hasn’t recognized the Afghan government’s legitimacy. Nor has the Taliban agreed to a ceasefire with Afghan forces, or offered any real indication that it seeks peace. Akhundzada’s victory declaration was littered with references to the Taliban’s “Islamic Emirate,” the same authoritarian regime the jihadists have been fighting to resurrect since 2001.

In his defense of the deal, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo trumpeted the Taliban’s supposed counterterrorism assurances. But the text of the agreement doesn’t support his claims. Pompeo told a national television audience that the Taliban “for the first time, have announced that they’re prepared to break with their historic ally, al-Qa’ida, who they’ve worked with much [to] the detriment of the United States of America.” Except, that is not what the Taliban’s political team agreed to in Doha.

Al-Qaeda is mentioned by name twice, in back-to-back passages that repeat the same assurance. The Taliban claims it will “prevent any group or individual, including al-Qa’ida, from using the soil of Afghanistan to threaten the security of the United States and its allies.” Without ironclad enforcement provisions, this is not a significant concession. The Taliban has been saying this all along.

The U.S. government pressured the Taliban to turn over Osama bin Laden more than 30 times between 1996, when the group solidified its control over much of Afghanistan, and the summer of 2001. Not only did the Taliban refuse, its representatives went so far as to claim that bin Laden was under wraps and posed no threat to the U.S. Obviously, that was a lie.

In the years after 9/11, the Taliban continued to insist that its terrain is off limits for both regional and international terrorists. In early 2019, for instance, the Taliban said it did “not allow anyone to use the soil of Afghanistan against other countries including neighboring countries.” That language is similar to the wording included in the Trump administration’s accord. It has never been true. Multiple international and regional terrorist organizations have fought alongside the Taliban in Afghanistan since 9/11, including al-Qaeda leaders with an eye on the West.

The State Department hasn’t explained why we should believe the Taliban now. The text of the deal doesn’t include any verification or enforcement mechanisms. It is possible that such measures are included in unreleased annexes, but there are still many questions concerning how this could be implemented. It is also dubious that the U.S. can continue to monitor the Taliban’s adherence after all American forces have been withdrawn from the country. There is also an issue of timing. The deal doesn’t specify how long the Taliban will supposedly keep al-Qaeda from plotting attacks against the U.S. from inside Afghanistan. Without a firm timeframe established, one could read the text as implying that this commitment only lasts as long as it takes the U.S. to get out.

A true renunciation of al-Qa’ida would entail Taliban admissions and commitments that are missing from the deal.

The Taliban has never come clean about its past, nor has the group renounced its decision to harbor Osama bin Laden and his men. Taliban founder Mullah Omar steadfastly stood by bin Laden both before and after 9/11. Omar, who eventually passed away in 2013, blamed America’s foreign policies for the hijackings. The Taliban has continued to justify al-Qaeda’s attacks in the West along the same lines. While negotiating with the U.S. last year, the Taliban argued that 9/11 was the result of America’s “interventionist policies,” while refusing to name al-Qaeda as the culprit. This is curious behavior for a group that has supposedly committed to prevent future al-Qaeda operations against the U.S.

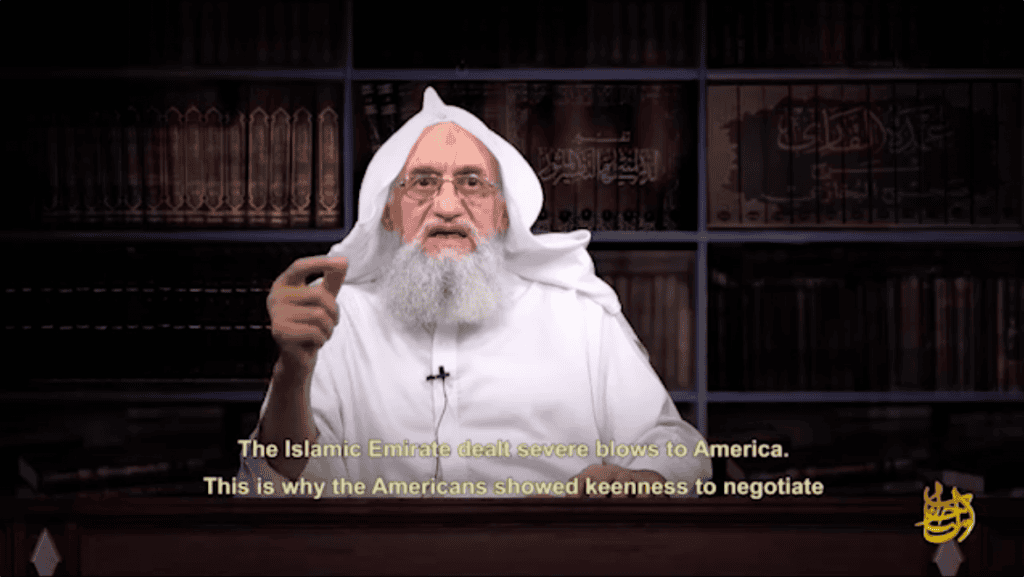

Just as bin Laden pledged his allegiance to Mullah Omar, an oath the al-Qaeda founder maintained until his dying day in 2011, bin Laden’s successor has sworn his own bayat (oath of fealty) to the Taliban’s current overall leader, Haibatullah Akhunzada. However, Ayman al-Zawahiri’s blood oath isn’t addressed in the accord. And Akhunzada didn’t mention it in his own post-deal message. In fact, the Taliban’s Voice of Jihad websites, which publish statements every day in several languages, have remained silent concerning al-Qaeda. It would be easy for Akhundzada to disavow Zawahiri, revoking whatever religious legitimacy al-Qaeda derives from the Taliban’s blessing. Thus far, Akhundzada hasn’t done so.

Sirajuddin Haqqani, Akhunzada’s top deputy and the Taliban’s military warlord, hasn’t renounced al-Qaeda either. Al-Qaeda’s senior leaders refer to both Akhundzada and Haqqani as “our emirs.” Jalaluddin Haqqani, Sirajuddin’s father, was one of bin Laden’s earliest and most influential benefactors. The Haqqanis, including Sirajuddin, have been in bed with al-Qaeda since the 1980s. Still, Sirajuddin hasn’t addressed the Haqqani-al-Qaeda nexus.

Pompeo claims that Taliban has agreed to go well beyond a mere renunciation of al-Qaeda, as the group will supposedly work with the U.S. to “destroy” Zawahiri’s organization inside Afghanistan. This would be a reversal of Taliban policy since the 1990s.

The State Department could point to three provisions — none of which specifically name al-Qaeda, or any other terrorist group for that matter – to justify Pompeo’s portrayal. The Taliban supposedly won’t cooperate with groups or individuals who threaten the U.S., or allow these anti-American entities to recruit, train or fundraise inside Afghanistan, or provide travel paperwork for international terrorists. While that may seem reassuring, the Taliban has easy workarounds. And again, no enforcement or verification mechanisms have been spelled out.

Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS), which answers directly to Zawahiri, was established in 2014 specifically to help the Taliban resurrect its Islamic Emirate. U.S. officials say that when AQIS members are captured in Afghanistan, they often do not self-identify as al-Qaeda members, but instead as warriors of the Islamic Emirate. This arrangement allows al-Qaeda to avoid international scrutiny. Consider that Asim Umar, the first emir of AQIS, was killed in a Taliban stronghold in Musa Qala, Helmand on Sept. 23, 2019. This was just a few weeks after Pompeo first declared that the Taliban was willing to “publicly and permanently” break with al-Qaeda. But the Taliban didn’t give up Umar, even though his AQIS network stretches well outside of Afghanistan’s borders, to Bangladesh, Burma, India, and Pakistan.

This sets up a test for Pompeo’s claims. In order for the Taliban to actively “destroy” al-Qaeda, it would have to uproot not only AQIS, but also an alphabet soup of other al-Qaeda-affiliated jihadist groups. This includes al-Qaeda-linked Central Asian and Uighur organizations, as well as Pakistani terrorists. If Pompeo’s claim is true, in the coming weeks, we should see the Taliban betray hundreds of jihadists, at least, including some high-profile figures.

If Secretary Pompeo is right, then Special Representative Zalmay Khalilzad has negotiated the greatest betrayal in the history of jihadism, with the Taliban breaking its quarter-century relationship with al-Qaeda. It would be a boon for counterterrorism efforts around the globe, as jihadists everywhere from West Africa to South Asia have held up the Taliban’s alliance with al-Qaeda as a model for jihadist unity.

If Pompeo is wrong, then President Trump’s State Department has exonerated and legitimized the Taliban on America’s way out the door. That certainly wasn’t necessary to withdraw troops from the country. Nor does it place America’s security interests first.