The Department of Justice has unsealed an updated indictment against Jehad Serwan Mostafa, an American who belongs to Shabaab and has served the al-Qaeda branch in a variety of capacities.

“We believe this defendant is the highest-ranking U.S. citizen fighting overseas with a terrorist organization,” U.S. Attorney Robert Brewer said. If true, then Mostafa is the most senior American to serve in groups such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State.

Mostafa, who was born in Wisconsin and resided in San Diego, California, was first charged in 2009, and that indictment was unsealed in 2010. Nine years later, the U.S. government thinks he is still playing a prominent role within Shabaab.

After graduating from college in San Diego in 2005, Mostafa left for Sana’a, Yemen and “then on to Somalia where he engaged in fighting against internationally supported Ethiopian forces,” according to the DOJ. He joined Shabaab and worked his way up his ranks.

The FBI alleges that Mostafa has worked for various parts of Shabaab’s organization, including in its media wing, while also training its fighters and “participating in attacks on Somali government forces and African Union troops.” By 2009, he “held leadership positions” within the al-Qaeda branch.

Earlier this year — a decade after Mostafa first became a senior Shabaab figure — the FBI learned that he had a leadership position within Shabaab’s “explosives department.” The FBI says Mostafa has been implicated in attacks using improvised explosive devices (IEDs). The U.S. government alleges that he “continues to play a critical role in planning operations directed against the Somali government and internationally supported African Union forces in Somalia and East Africa.”

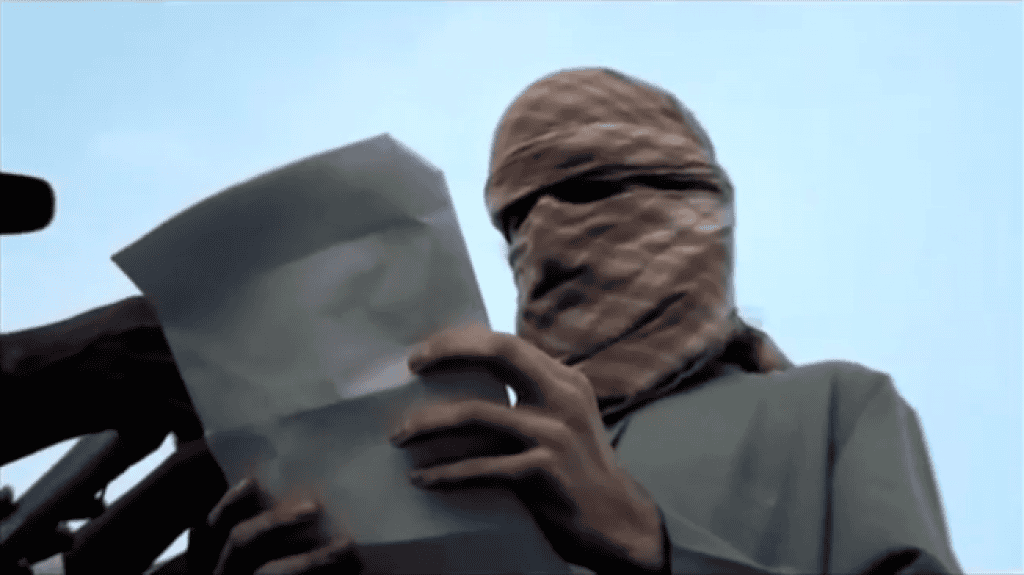

Mostafa garnered some public attention in 2011, when he appeared in a Shabaab video that was recorded at a camp outside of Mogadishu. The FBI subsequently confirmed to FDD’s Long War Journal that the man seen in the video, identified as Abu Abdullah al-Muhajir, was in fact Mostafa.

The footage was recorded an event named: “Al Qaeda campaign on behalf of the martyr Bin Laden. Charity relief for those affected by the drought.”

Speaking English with his American accent, Mostafa claimed to be a representative of bin Laden’s successor, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and his “brothers in al-Qaeda.” Mostafa said that he and others in attendance “remember the role played by our beloved sheikh, Sheikh Usama bin Laden, may Allah have mercy upon him.” As he lauded al-Qaeda’s founder, the American citizen also announced the delivery of various foodstuffs and other provisions to the Somalis who were struggling to survive the shortages caused by widespread famine.

The FBI describes Mostafa’s appearance at the Shabaab camp as a “media stunt,” saying it was part of “his efforts to facilitate al-Shabaab’s relationship with other terrorist groups and role in external operations.” There is little doubt that the event was part of al-Qaeda’s propaganda efforts inside Somalia. Al-Qaeda regularly exploits local grievances and other issues to build a broader base of support for its ideology and organization.

However, Mostafa’s presence appears to have been more significant than just a propaganda stunt. During his masked appearance at the camp, Mostafa was accompanied by Sheikh Ali Mohamud Rage, Shabaab’s top spokesman. Rage continues to be openly loyal to al-Qaeda’s senior leadership, as he released a statement earlier this year expressing his fealty to both Zawahiri and the Taliban’s emir, Hibatullah Akhundzada.

And even though Shabaab’s role as an al-Qaeda branch wasn’t officially announced at the time of Mostafa’s appearance, it was clearly part of Osama bin Laden’s and Ayman al-Zawahiri’s network well beforehand.

Documents recovered in bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound show that the al-Qaeda founder ordered Shabaab to refrain from publicly announcing its allegiance to al-Qaeda’s senior leadership, but the group’s fealty was not in question.

For instance, in an Aug. 7, 2010, letter to Ahmed Abdi Godane (a.k.a. Mukhtar Abu Zubayr), who was then the emir of Shabaab, bin Laden specifically addressed “the issue of unity,” writing that “this obligation should be carried out legitimately and through unannounced secret messaging.” The matter was to be spread “among the people of Somalia, without any official declaration by any officers on our side or your side, that the unity has taken place.” Bin Laden further advised that the “brothers” in Somalia should “say that there is a relationship with al-Qaeda, which is simply a brotherly Islamic connection and nothing more,” as this could be neither denied nor proven.

Bin Laden carefully explained his reasoning, telling Godane that if “the matter [of unity] becomes declared and out in the open,” then “it would have the enemies escalate their anger and mobilize against you.” This “is what happened to the brothers in Iraq or Algeria” — a reference to al-Qaeda in Iraq and al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). Regardless, bin Laden wrote, it was “true that the enemies will find out inevitably,” because “this matter cannot be hidden, especially when people go around and spread this news.”

Although some analysts concluded that bin Laden had denied Godane’s request for unity, this was not the case. If he hadn’t accepted Godane’s fealty, then there was nothing to be hidden in the first place. Still, bin Laden wrote, an “official declaration remains to be the master for all proof.” The al-Qaeda founder explained that by keeping the merger secret, Muslims throughout the region could continue to do business with Shabaab’s upstart emirate, without the stigma of interacting with al-Qaeda.

FDD’s Long War Journal found that Bin Laden’s letter to Godane was actually an attachment to a longer missive he had written to his right-hand man, Atiyah Abd-al-Rahman. In it, bin Laden explained to Rahman what Shabaab’s bayat, or oath of allegiance, to him should entail. “As for the pledge of allegiance from the brothers in Somalia, let it be based on waging jihad to establish the Caliphate,” bin Laden wrote. Bin Laden also explained why Abu Yahya al-Libi, a top al-Qaeda ideologue, needed to spend his time helping Shabaab “now that they have joined us.” Shabaab controlled “an Islamic emirate on the ground with millions of subjects” and this required “close follow-up,” bin Laden surmised. He continued: “We also must provide religious research that meets their needs.” The “gravity of the responsibility upon our shoulders now that they have joined us” meant that Libi should “dedicate a big part of his time for this mission, and not just to prepare the research they ask him for, but also to anticipate what they will need and prepare it for them.” In addition to bin Laden, Rahman and Libi were subsequently killed by the U.S.

Within months after Mostafa’s appearance at the Shabaab camp, al-Qaeda officially announced that the group was part of its international organization — thereby ending Osama bin Laden’s desire for a thinly-veiled allegiance. In the years since then, Shabaab has been openly loyal to Zawahiri, rejecting the Islamic State’s caliphate and cracking down on dissenters.

Throughout all of this, and more, Mostafa has apparently survived in Somalia.

The U.S. government first offered a reward of up to $5 million for information on his whereabouts in 2013. The U.S. has now reiterated that reward offer.

The FBI has highlighted some identifying information for Mostafa, including images of a scar on his right hand, in the hopes that someone will provide a tip regarding his precise location.