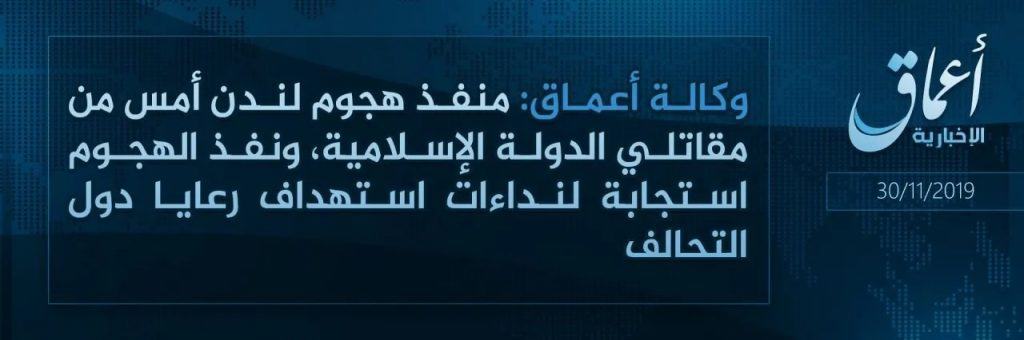

On Nov. 29, Usman Khan slashed and stabbed at pedestrians on London Bridge, killing two people. The Islamic State has claimed credit for the murders, describing Khan as its “fighter” and attributing his actions to the group’s calls for violence in countries belonging to the anti-caliphate coalition. Pro-Islamic State social media channels have also promoted Khan with imagery portraying him as a soldier of the terror group.

However, Khan was first drawn to jihadism years before the rise of the Islamic State’s so-called caliphate. He was well-known to counterterrorism officials because of his pro-al-Qaeda leanings and attraction to the teachings of Anwar al-Awlaki, a prominent Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) ideologue who both inspired and directly oversaw a string of plots in the West. Indeed, Khan is the latest terrorist to be influenced by al-Qaeda, only to have the Islamic State claim him as its own.

Khan was 19 years-old when British authorities arrested him and others in Dec. 2010. According to Reuters, Khan’s comrades had discussed the possibility of placing a bomb inside a toilet in the London Stock Exchange. Alternatively, Khan and others considered establishing a training camp in Kashmir. After training, they contemplated carrying out attacks in Kashmir, or back in the UK.

“It was envisaged by them all that ultimately they, and the other recruits, may return to the UK as trained and experienced terrorists available to perform terrorist attacks in this country,” Alan Wilkie, a British judge, surmised, according to Reuters.

The tentacles of Khan’s organization, in which he was a leading member, stretched across London, Cardiff and Stoke. British authorities found that the contingent based in Stoke, including Khan, were the most “serious” potential threats.

In December 2010, according to a summary prepared by a British court, Khan’s conversations with other would-be offenders were recorded. In one such conversation, in which he attempted to “radicalize another male,” Khan explained it was his intention to leave for a madrassa in Kashmir that would be used for training for jihad. “The Stoke group were to fund the camp and recruit men for it,” with Khan expecting “only victory, martyrdom or imprisonment,” according to the court summary.

Khan and another conspirator were to attend the camp in the near future at the time of their arrest, and they contemplated “terrorist operations in the UK to be perpetrated by some graduates of the training camp at some future date.”

On Dec. 15, 2010, Khan was overheard discussing AQAP’s Inspire magazine and, specifically, the “pipe bomb recipe” in its first issue. The British court noted that Khan “appeared to have memorized” the pipe bomb recipe and discussed the “possibility of using the device to attack the English Defence League,” a far-right organization in the UK. Khan also “explained how Inspire could be obtained from the internet.”

The British court further explained that while Khan and his compatriots did not belong “directly to Al Qaeda (AQ),” they were radicalized “through the internet, inspired by the ideology and methodology of Anwar Al Awlaki…and the AQ magazine ‘Inspire’ which he wrote, copies of which were found on computer equipment seized from the homes associated with many of the defendants.”

Al-Qaeda and AQAP weren’t Khan’s only sources of inspiration. The Guardian reports that Khan “was a student and close friend of” Anjem Choudary, who led al-Muhajiroun, an extremist organization that has been linked to a number of jihadis. While the precise details of these ties remain to be filled in, it is clear from the British court record that Khan was influenced by Awlaki and AQAP’s Inspire long before the Islamic State claimed him as its man.

And Khan isn’t alone in this regard. In a number of cases, jihadists were first drawn to al-Qaeda, only to be fascinated with the Islamic State after its initial rise.

As FDD’s Long War Journal has reported in the past, several terrorist attacks in the U.S. were conducted by aspiring jihadists who first studied Awlaki’s teachings, but the Islamic State later claimed were its fighters.

In Dec. 2015, Syed Rizwan Farook and his wife, Tashfeen Malik, killed 14 people in a mass shooting in San Bernardino, Calif. Farook and his friend had studied Awlaki’s teachings years beforehand and also utilized the pipe bomb designs offered in Inspire.

Omar Mateen, who killed 49 people at a nightclub in Orlando, Fla. in June 2015, also reportedly listened to Awlaki’s lectures. Both the San Bernardino shooters and Mateen pledged allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and the Islamic State claimed that they acted on its behalf.

Another example arose in Sept. 2016, when Ahmad Khan Rahami placed improvised explosive devices (IEDs) at locations in New York and New Jersey. Rahami referenced Awlaki, Osama bin Laden and Islamic State spokesman Abu Muhammad al-Adnani as ideological guides in his notebook.

In Dec. 2018, the FBI arrested Daniel Joseph, a 21-year-old who was allegedly planning to open fire at a synagogue in Toledo. Joseph had picked two synagogues as potential targets. Joseph was also influenced by both Awlaki and the Islamic State. [See FDD’s Long War Journal report, Ohio man allegedly inspired by Anwar al-Awlaki, Islamic State.]

Khan’s stabbing spree also isn’t the first attack on London Bridge that was claimed by the Islamic State. In June 2017, the group issued a statement saying that a “unit” of its “fighters” carried out a joint vehicular-knife assault on pedestrians on London Bridge and at the nearby Borough Market. Like Khan, at least one of those three terrorists, Khuram Shazad Butt, was well-known to authorities beforehand. Butt was also associated with Al-Muhajiroun.