Decades of deceit and mistakes have led us to the brink of a major foreign policy failure. The Trump administration is reportedly on the cusp of cutting a shameful deal with the Taliban that will provide the U.S. military cover to withdrawal from Afghanistan. In order to help sell that deal, the U.S. will disregard and obfuscate the Taliban’s generations-long, steadfast alliance with al Qaeda.

“U.S. officials constantly said they were making progress,” The Washington Post reported today. “They were not, and they knew it.”

The Post report will not be shocking to longtime readers of FDD’s Long War Journal. Over the past decade, we have documented the lies and deceptions from presidents, senior officials and high-ranking military officers.

The Post’s analysis is based on more than 2,000 interviews compiled by the Special Investigator General for Afghanistan Reconstruction. Ironically, some of those interviewed who are critical of U.S. efforts in Afghanistan are the very same officials whose failed policies and ideas somehow remain promoted to this day.

In our estimation, the greatest problem the U.S. has faced in nearly two decades of war in Afghanistan is the inability to define the enemy. The Post touched on that problem when it asked the question: “Was al-Qaeda the enemy, or the Taliban?”

The US government failed to settle on an answer to that question.

In 2009, when the debate over U.S. strategy in Afghanistan and the nature of the enemy was raging, we noted that al Qaeda was the tip of the jihadist spear in Afghanistan, it remained closely allied with the Taliban, and that a comprehensive strategy was needed to deal with Pakistan and Iran – two major backers of the Taliban – in order to achieve success.

Instead of taking a holistic approach to the Afghanistan problem, the Obama administration chose a limited counterinsurgency strategy against the Taliban while targeting al Qaeda in Pakistan with drone strikes.

Pakistan, the Taliban’s main backer, was never truly held to account for its role in destabilizing Afghanistan. One decade later, the Taliban is as strong as it has been since the U.S. invaded Afghanistan in 2001, while al Qaeda remains a steadfast ally.

And yet, many U.S. policymakers continue to attempt to disconnect the dots between al Qaeda and the Taliban. This must be done in order to extricate the U.S. from Afghanistan and to paper over nearly two decades of failed policy.

The U.S. government and military’s efforts to muddle and spin the problems in Afghanistan are legion, as detailed by SIGAR along the way. Many of these lies and deceptions have been visible to the public, and at FDD’s Long War Journal we have consistently documented many of them.

A small selection of those reports, which provide a window into how U.S. has arrived at this critical juncture, are reproduced below:

“50 to 100″ al Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan: In 2010, then-CIA Director Leon Panetta claimed that al Qaeda maintained a small footprint of fighters, “maybe 50 to 100, maybe less,” inside Afghanistan. The bulk of al Qaeda’s forces in the region were based in Pakistan’s tribal areas, Panetta maintained. This is where the U.S. focused its drone campaign, particularly in Pakistan’s tribal agencies of North and South Waziristan, where 95 percent of the strikes took place. The Obama administration, which sought to extricate the U.S. from Afghanistan, downplayed al Qaeda’s presence in the country in order to sell withdrawal. If al Qaeda was no longer a threat there, the U.S. had no reason to be there, the administration argued.

The faulty “50 to 100” estimate of al Qaeda in Afghanistan remained steady for six years, even though U.S. military press releases that were published between 2007 to 2013 showed this estimate was wildly inaccurate (the U.S. military stopped reporting on raids against al Qaeda in the summer of 2013). Additionally, the U.S. military insisted al Qaeda was confined to the northeastern provinces of Kunar and Nuristan (another fallacy; by May 2019, the U.S. commander for Afghanistan said that al Qaeda operates “across the country”).

The 50 to 100 fallacy was blown apart in Oct. 2015 when the military raided two large al Qaeda training facilities in the southeastern province of Kandahar and killed more than 150 al Qaeda fighters. The military was then forced to revise its estimate of al Qaeda in Afghanistan to upwards of 300 operatives. By Dec. 2016, the U.S. military reported that it killed or captured 250 al Qaeda operatives in Afghanistan that year alone.

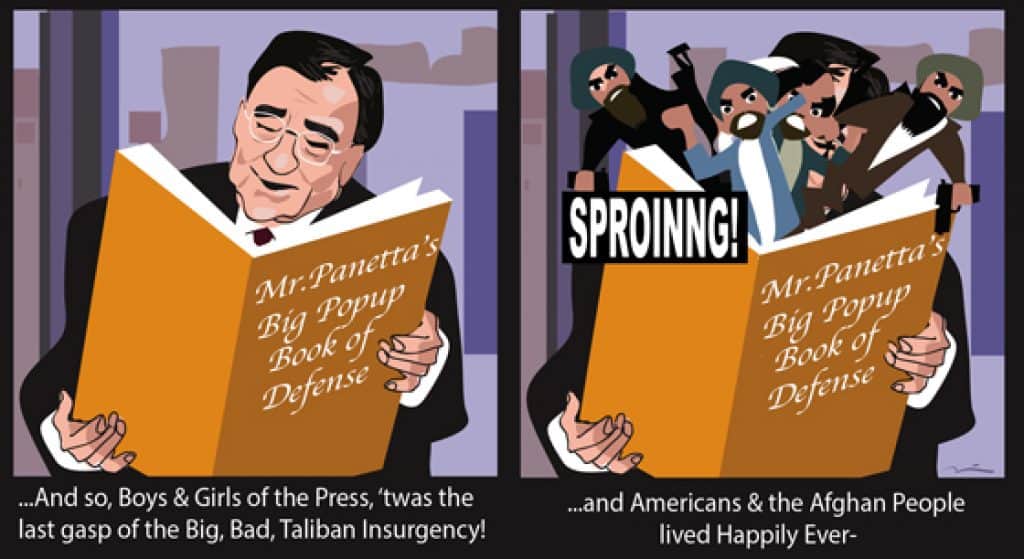

“Last gasp” of the dying Taliban: In Sept. 2012, who was now Secretary of Defense, responded to the dramatic rise in green-on-blue or insider attacks, where Afghan security personnel turn their weapons on U.S. and Coalition forces, by claiming it was the “last gasp” of the dying Taliban. Panetta’s comment was so absurd that we took the unusual step of commissioning a comic to highlight this fact.

Taliban’s momentum is broken: “We’ve broken the Taliban’s momentum in Afghanistan, and begun the transition to an Afghan lead,” President Barack Obama proudly proclaimed on Sept. 1, 2012. “Next month the last of the troops I ordered as part of the surge against the Taliban will come home, and by 2014, the transition to Afghan lead will be complete.”

LWJ looked at the U.S. and NATO’s own data on the security situation in Afghanistan, which attempted to paint a rosy picture, and concluded that the Taliban’s momentum was not near broken.

Mapping Taliban control no more: In 2015, LWJ began mapping the Taliban controlled and contested districts of Afghanistan. Several months later, the U.S. military began producing its own map, which was reproduced by SIGAR in Nov. 2017. General John W. Nicholson Jr. then-commander of Resolute Support and U.S. Forces Afghanistan called “population control” the “most telling” metric for success; Taliban control of a district means that the Taliban controls its population.

The U.S. military had hoped the map would show how Afghan security forces were regaining control of the country and increase the number of Afghans living under the government’s control. But the U.S. military’s assessment, which was pollyannish to begin with, was flawed as it downplayed areas that were contested or under Taliban control. Even so, the data – which was released quarterly – showed slow but steady Taliban gains. In an attempt to combat this negative message, the U.S. military attempted to redefine terms to obfuscate Taliban control, or hide the status of districts.

By Oct. 2018, the U.S. discontinued the gathering and release of data related to population and district control, arguing the information was “of limited decision-making value” to military leaders. The U.S. military, whose primary mission in Afghanistan should be securing the country, was so vested in a peace deal with the Taliban that it chose to instead discard information that would illustrate the security situation.

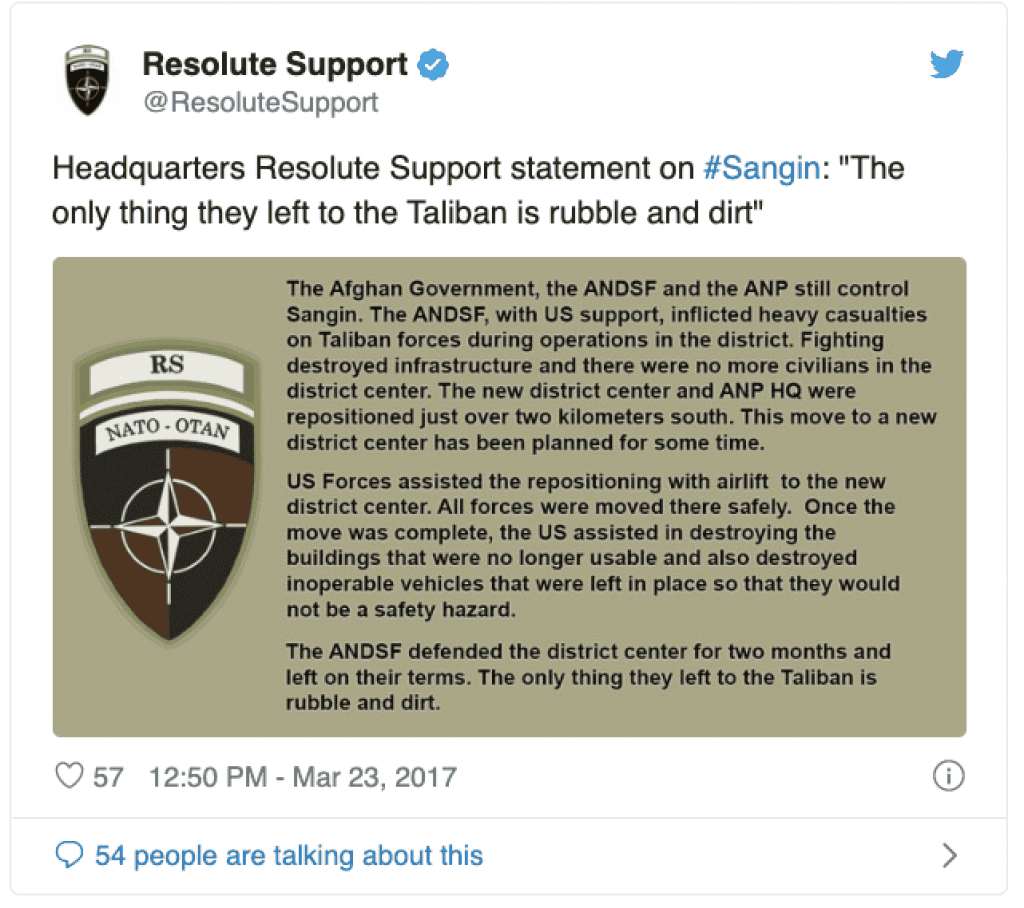

We had to destroy the district center to save it: While this is a subset of the issue with the mapping of Taliban controlled and contested areas, the spin by Resolute Support on the loss of the Sangin district center in March 2017 was so egregious that it deserves its own mention. After months of heavy fighting in Sangin, the U.S. military airlifted Afghan troops from the district center, and then proceeded to destroy it as well as abandoned Afghan military equipment from the air. Resolute Support then crowed that “The only thing they left to the Taliban is rubble and dirt,” and touted that it created a new district center just miles away. Thus, the U.S. military could claim Sangin was in Afghan government control. Problem solved.

The desperate Taliban is losing ground: In May 2018, while the Taliban was launching a series of deadly suicide assaults, then-Pentagon Chief Spokesperson Dana W. White described the Taliban as “desperate” because it is “losing ground.” Additionally, White said that over the last year, “things are moving in the right direction,” even though the U.S. military’s own data on Taliban controlled and contested districts refuted this assertion. White doubled down on these statements, even after the Taliban overran Farah City later that month as well as took control of several district centers. “The Taliban has not had the initiative,” White stated, and claimed the Taliban only hit “soft targets.” The Taliban was neither desperate, losing ground, nor hitting soft targets. And things were not and still are not moving in the right direction.

The Taliban’s defeat of Islamic State in Jawzjan is a counterterrorism success: At the end of July 2018, the Taliban massed its forces and targeted a large cadre of Islamic State fighters that were based in Darzab district in Jawzjan province. The Taliban operation was decisive, and it did what the Afghan military could not do: mass in Darzab and defeat the Islamic State. The Taliban’s ability to do what the Afghan government and military could not do should have given Resolute Support and the U.S. military pause. Instead, they chose to highlight Jawzjan as a counterterrorism success. Nicholson himself pointed to the Islamic State’s defeat as “a recent success” and evidence that the security situation Afghanistan is improving while ignoring the Taliban’s victory.

Khalilzad flip flops on Taliban, al Qaeda, and Pakistan: While testifying before the House Foreign Affairs Committee (HFAC) in July 2016, Zalmay Khalilzad, the former U.S. ambassador to Afghanistan, said that Pakistan should be designated as a State Sponsor of Terrorism because it is an ardent supporter of the Taliban [Full disclosure: this story’s author, Bill Roggio, also testified at this hearing].

Khalilzad described the Taliban as an “extremist organization” with enduring ties to al Qaeda. Just over two years later, Khalilzad was appointed the Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation, the man tasked with cutting a peace deal with the Taliban. Since his appointment, Khalilzad has flip-flopped on his views, stating that the Pakistani government is a partner for peace and predicted that the Taliban would break ties with al Qaeda. Khalilzad has not provided explanation for his 180 degree pivot.

Whitewashing the Taliban’s ties with al Qaeda for “peace”

As the U.S. government and military failed to define the enemy and its multitude of policies and strategies failed to defeat the Taliban, the desire to secure a face-saving withdrawal has gained strength. To accomplish this, the theory goes, the U.S. must secure a so-called “peace agreement” with the Taliban. In order to secure this agreement, it is necessary to whitewash the Taliban’s ties with al Qaeda. This would allow the U.S. to “leave without losing.“

The irony in The Washington Post‘s report is that some of the same U.S. officials who have been directly responsible for failed U.S. policy in Afghanistan have now been tasked with securing a deal with the Taliban, which will be anything but peaceful. Khalilzad has deceived the American public on Pakistan and the Taliban-al Qaeda relationship, and he has done so to support to the Taliban’s current negotiating position.

Khalilzad is by no means alone. Douglas Lute, who has served as a key advisor on Afghanistan in both the Bush and Obama administrations, is favorably cited in The Post article for his criticism of U.S. policy, which he actually played a key role in developing. He has cheered the Trump administration’s outreach to the Taliban. Given his years of failure, why should Lute’s views be trusted now?

After two decades of failure, the same officials critical of U.S. policy in Afghanistan have developed it, lied about it, and continue to comment on it. Their lies and failures, at a minimum, should bar them from government service, yet those in charge continue to hand them the keys, and we are left to listen to them as if they are an authority.