On May 10, al Qaeda’s propaganda arm, As Sahab, released Ayman al-Zawahiri’s eulogy for Jalaluddin Haqqani — an early ally of Osama bin Laden who also served in the Taliban’s Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. Haqqani and his eponymous network were once backed by America, via the CIA, during the 1980s jihad against the Soviets in Afghanistan.

But after 9/11 the Haqqani Network bedeviled the US and its allies by harbored al Qaeda’s men while also closely cooperating with them on the battlefield in Afghanistan.

The Taliban announced the elderly Haqqani’s death in Sept. 2018. Al Qaeda released a two-page eulogy days later, glorifying Haqqani as a steadfast warrior and describing him as an ideological “brother” of Osama bin Laden.

But it wasn’t until earlier this month, eight months after the Taliban announced Haqqani’s death, that As Sahab disseminated its video tribute online. Zawahiri regularly produces audio and video messages, so it isn’t clear why there was a delay. The eulogy was posted on al Qaeda’s Telegram channel, which is often disrupted, as well as on affiliated social media sites and As Sahab’s website.

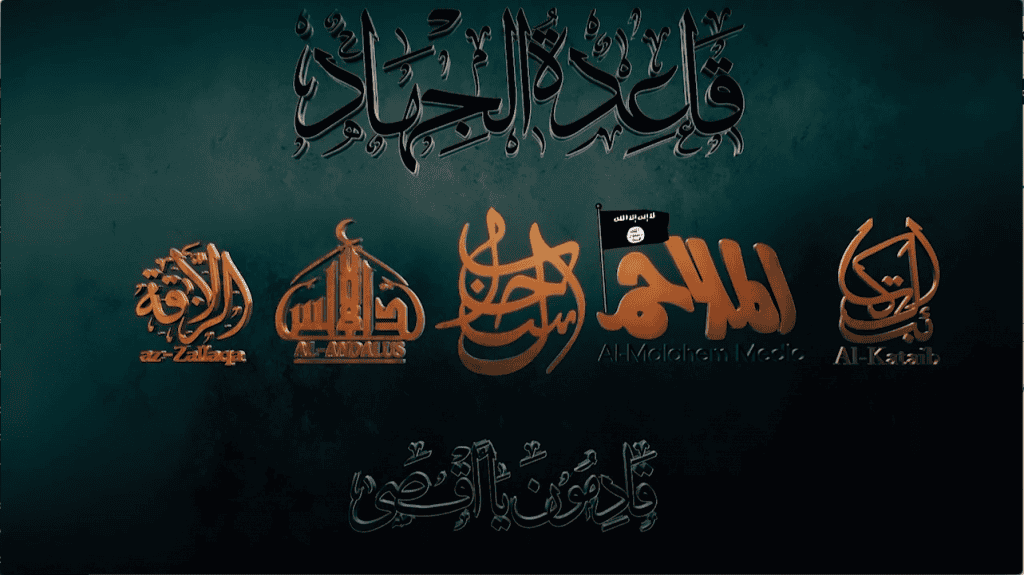

Early on in video, which is dedicated to Haqqani, described as the “The Lion of Islam,” As Sahab flashes the image below.

The image displays the logo for As Sahab and the media houses of four other al Qaeda branches: Az-Zallaqa (Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin, JNIM, or the “Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims”), Al-Andalus Media (Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb), Al-Malahem Media (Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula), and Al-Kataib Media (Shabaab in Somalia).

The inclusion of these logos is intended to underscore the cohesion of al Qaeda’s international media team. (Notably absent is the logo for any jihadist media arm in Syria.)

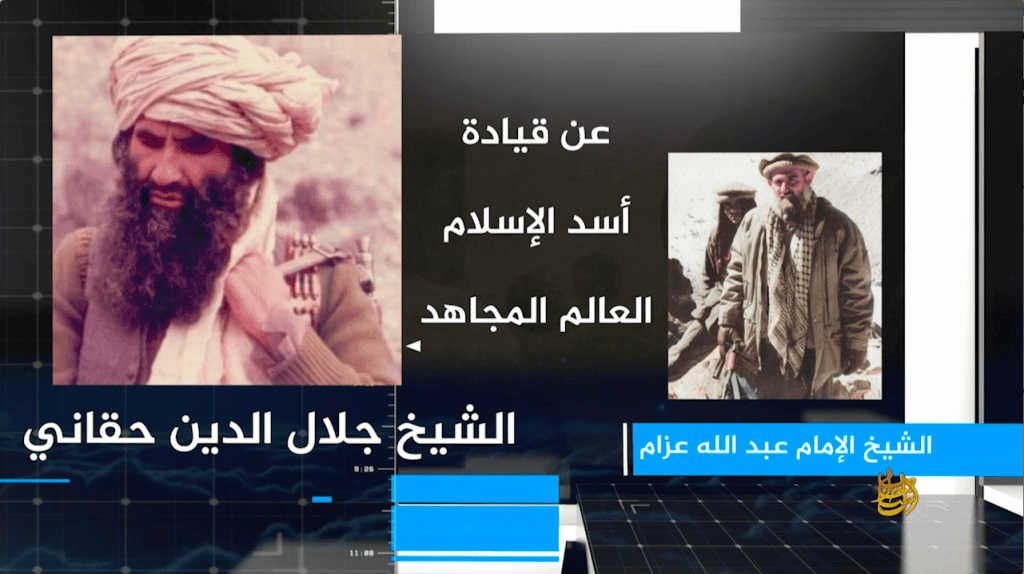

Zawahiri’s eulogy is spliced together with other footage, including images of Haqqani and Abdullah Azzam side-by-side. Azzam was a close comrade of Haqqani’s and praised his commitment to jihad.

Toward the end of the video tribute, Zawahiri spends several minutes showering Haqqani with praise, describing him as a “hero” and the “eminent sheikh.”

Zawahiri offers his condolences on behalf of the entire al Qaeda organization to the “Emir of the Faithful” Hibatallah Akhundzada (the Taliban’s overall leader), the Taliban’s highest shura (or consultative) council, all of the Islamic Emirate’s “officials and mujahideen,” as well as Haqqani’s family. The al Qaeda leader specifically names Haqqani’s son, Sirajuddin, who currently serves as the Taliban’s #2 leader. Zawahiri prays for Allah to provide Siraj, whom he describes as his “eminence,” with comfort and “patience.”

Al Qaeda also specifically addressed Akhundzada and Siraj Haqqani as “our emirs in the Islamic Emirate” in its written statement concerning Jalaluddin’s death last year. Al Qaeda’s general command said at the time that it took “solace in the fact” that Siraj is the “deputy of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan’s Emir of the Faithful” and is following in his father’s “footsteps.”

In the new video, Zawahiri describes Haqqani’s death as a “loss” for the mujahideen, and especially the “migrants” who emigrated to Pakistan and Afghanistan for jihad. Haqqani’s role in housing the first generation of Arab fighters during the war against the Soviets has been well-documented. Among Haqqani’s guests were some of al Qaeda’s first leaders, so Zawahiri’s decision to highlight this aspect of his career is unsurprising.

Zawahiri also praises Haqqani’s “devotion” to both jihad and the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, which the elderly ideologue joined in the mid-1990s and then served as an official. Zawahiri concludes his eulogy by asking Allah to grant him “high status,” purify his soul of his sins, and place his grave in the “meadows of paradise.”

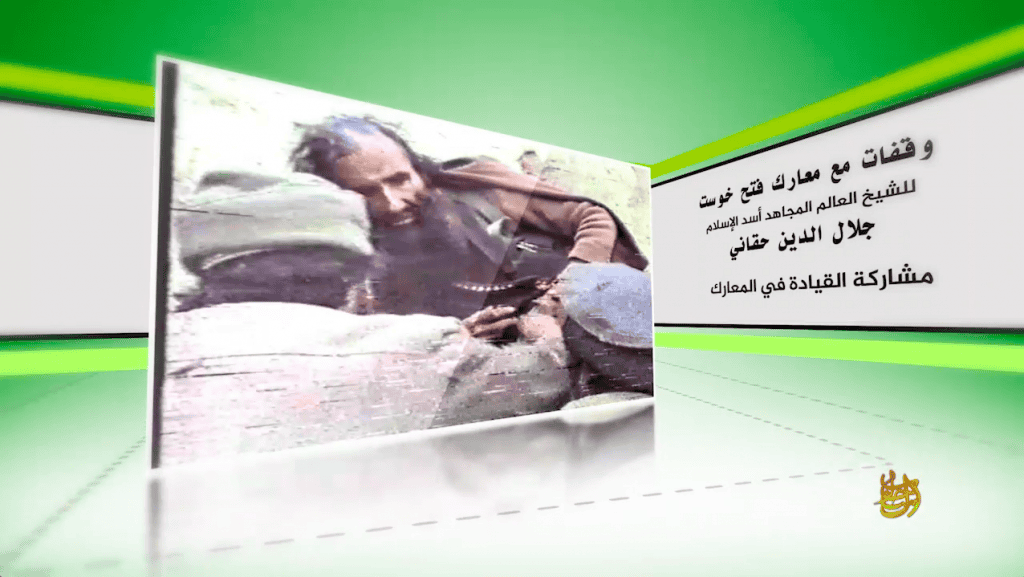

Before Zawahiri speaks, As Sahab includes archival footage of Haqqani sitting on the ground among a gathering of his comrades. He discusses the Battle of Khost – a key event in the early 1990s. Haqqani explains how he and his men battled the “atheists” and “communists” for control of Khost, eventually encircling the city by seizing control of its surrounding roads. The jihadists also sought to prevent the enemy’s aircraft from landing by targeting key runways. At some point, Haqqani claims, the Soviets even mistakenly dropped anti-tank shells that proved decisive in the battle.

As Haqqani explains his strategy for capturing Khost, maps are displayed on screen to help viewers conceptualize the battle plan.

The battle for Khost was an especially difficult affair, Haqqani told his men in the footage, with the mujahideen suffering heavy casualties. Haqqani himself was wounded and the video documents the moment when his men helped him get off the ground and limp away.

In part of his talk, Haqqani explained how his men treated captured prisoners, separating foot soldiers from commanders and even sending some of the detainees to religious school for indoctrination.

As Sahab’s tribute does not mention the fact that Jalaluddin Haqqani and his men once received support from the US, and have long been allied with Pakistani intelligence. These facts, and others, complicate the jihadists’ narrative with respect to the 1980s war in Afghanistan. The jihadists would like people to believe that their victory was owed to their faith alone — and not the substantial resources of a world power they would later fight as their principal enemy.

The US State Department cheered on Haqqani’s victory against Soviet-backed forces at Khost in early April 1991. The New York Times reported at the time that the CIA was providing “$200 million a year in military aid” to the “rebels.” The Times also reported that the Soviets were still aiding President Najibullah’s forces at Khost despite announcing their withdrawal from Afghanistan two years earlier. The Soviet Union would fall later that same year.

After 9/11, Jalaluddin Haqqani and then his heirs helped ensnare the United States in a prolonged conflict.