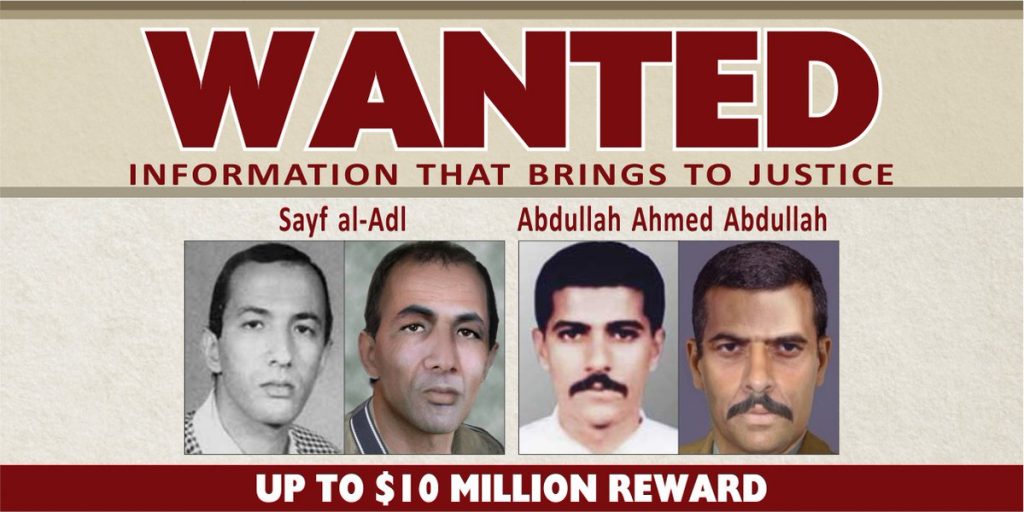

On Aug. 8, the US State Department announced that it had increased its reward for information concerning the whereabouts of two senior al Qaeda figures. The two “key leaders” are al Qaeda veterans, Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah and Saif al-Adel, both of whom have been wanted since 1998. State’s reward for information leading to their “location, arrest, or conviction” has now been doubled — from $5 million to $10 million.

The US first indicted the pair in Nov. 1998, after they were implicated in the American embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania several months earlier. Those attacks were al Qaeda’s most devastating prior to 9/11, killing 224 civilians and wounding thousands of others.

After 9/11, the two fled to Iran, where their status has been murky at times.

The State Department did not offer any information concerning their current activities, nor did Foggy Bottom explain why its reward offer was increased now.

But according to an al Qaeda operative in Syria, the two al Qaeda managers were operating inside Iran as of last year. They were even reportedly acting as Ayman al Zawahiri’s chief deputies while living on Iranian soil. In that role, they were asked to weigh in on a fierce disagreement between jihadists in Syria.

This assessment was confirmed by the United Nations in a newly-released report. The UN found that Ayman al-Zawahiri and his “lieutenants based in the Islamic Republic of Iran were able to influence disputes among the fighters in Idlib,” Syria.

The UN names these lieutenants as Saif al-Adel and Abu Muhammad Al-Masri. The latter figure is Abdullah Ahmed Abdullah, as Abu Muhammad al-Masri is one of his well-known aliases.

Both men are currently playing key roles in al Qaeda’s global network — from inside Iran.*

Longstanding ties

Al-Adel’s ties to Iran and its chief terrorist proxy, Hezbollah, date to the early 1990s. During the US embassy bombings trial in early 2001, an al Qaeda defector named Jamal al-Fadl fingered al-Adel as one of the al Qaeda members who received Iran’s and Hezbollah’s explosives training. The 9/11 Commission later found that al Qaeda used this training to develop the “tactical expertise” necessary to conduct the embassy bombings, which were modeled after Hezbollah’s attacks on American and Western forces in Lebanon in the early 1980s.

Abdullah and al-Adel were both originally members of the Egyptian Islamic Jihad (EIJ), a jihadist group that formally merged with bin Laden’s venture prior to 9/11. The EIJ was closely allied with al Qaeda well before their merger, with EIJ operatives performing various tasks for bin Laden.

US officials learned during the 1990s that the EIJ was operating inside Iran. For instance, former counterterrorism official Richard Clarke writes in Against All Enemies that “Iran provided al Qaeda safe haven before and after September 11,” with al Qaeda “regularly” using “Iranian territory for transit and sanctuary prior to” the hijackings.

Clarke added that “Al Qaeda’s Egyptian branch, Egyptian Islamic Jihad, operated openly in Tehran,” so it “is no coincidence that many of the al Qaeda management team, or Shura Council, moved across the border into Iran after US forces invaded Afghanistan.” Al-Adel and Abdullah were among those members of al Qaeda’s management cadre.

US intelligence kept tabs on al-Adel’s activities inside Iran post-9/11. In his autobiography, At the Center of the Storm, former Director of Central Intelligence George Tenet writes that the CIA collected troubling intelligence on al-Adel’s role in al Qaeda’s pursuit of nuclear or radiological weapons.

“From the end of 2002 to the spring of 2003, we received a stream of reliable reporting that the senior al Qaeda leadership in Saudi Arabia was negotiating for the purchase of three Russian nuclear devices,” Tenet explains. “Saudi al Qaeda chief Abu Bakr relayed the offer directly to the al Qaeda leadership in Iran, where Saif al Adel and Abdel al Aziz al Masri (described as al Qaeda’s ‘nuclear chief’ by Khalid Sheikh Mohammed) were reportedly being held under a loose form of house arrest by the Iranian regime.”

Al Adel told Abu Bakr “that no price was too high to pay if they could get their hands on such weapons,” according to Tenet. But al Adel “cautioned” against “scams,” saying that “Pakistani specialists should be brought to Saudi Arabia to inspect the merchandise prior to purchase.”

It is likely that the devices were not real nuclear weapons — if they existed at all. However, al Adel’s “house arrest” inside Iran at the time obviously was not too stringent if he was allowed to discuss the possible acquisition of the world’s most dangerous weapons. Tenet says that the CIA passed information about these activities “to the Iranians in the hope that they would recognize our common interest in preventing any attack against US interests.”

The US continued to monitor Al-Adel’s status inside Iran as of mid-2003. On May 12 of that year, al Qaeda bombers struck in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, killing more than 30 people. American intelligence suspected that al-Adel may have played a role in the attack. “The United States has intercepted communications strongly suggesting that a small cell of leaders of Al Qaeda in Iran directed last week’s terrorist attacks in Saudi Arabia,” The New York Times reported. However, it “was not clear whether Saif al-Adel…had a hand in the operation.” The al Qaeda members in Iran were suspected of involvement in other international plots as well, as some reports indicated that Saad bin Laden, Osama’s son, was tied to the terrorists responsible for the May 16, 2003 bombings in Casablanca, Morocco.

It often wasn’t clear in the years that followed what exactly al-Adel, Abdullah and other al Qaeda leaders were doing inside Iran. They were placed in a stricter form of detention at some point.

In addition to Saad bin Laden, other members of Osama’s family, including his son Hamza, fled to Iran after 9/11 as well. While in Iran, Hamza bin Laden married Abdullah’s daughter. A video of their wedding was found in Osama bin Laden’s Abbottabad compound and released by the CIA last year. Although Hamza was not under duress at the time of his marriage, his detention in Iran later became a source of tension between the Iranian regime and al Qaeda.

Still, Hamza used his time inside Iran to learn from the al Qaeda veterans detained alongside him. In an Aug. 2015 message, Hamza named his mentors as al-Adel, Abdullah (also known as Abu Muhammad al-Masri), as well as others who were held in Iran.

Osama bin Laden’s files show that al Qaeda was eager to welcome al-Adel and Abdullah back into the fold. Al Qaeda sought to free its leadership figures from Iranian custody, even kidnapping more than one Iranian to force a swap.

Finally, in 2015, al-Adel and Abdullah were among the several key al Qaeda figures who were reportedly released as part of a hostage exchange. According to press reports at the time, five veteran al Qaeda leaders were released in exchange for an Iranian diplomat who had been kidnapped in Yemen.

Al Qaeda operative says al-Adel and Abdullah are “not imprisoned” inside Iran

Approximately a year after their reported release, al-Adel and Abdullah became embroiled in the controversy over Al Nusrah Front’s decision to reposition itself as an independent entity. Al Nusrah Front in Syria was an official branch of al Qaeda. But Al Nusrah’s emir, Abu Muhammad al-Julani, announced in July 2016 that his group was rebranding itself as Jabhat Fath al-Sham (JFS) and wouldn’t be affiliated with any “external,” or foreign, “entities.” In Jan. 2017, JFS merged with several other entities to form Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a coalition which has since fractured.

The formation of JFS and then HTS proved to be especially controversial within al Qaeda circles, with some claiming that Julani had broken his oath of allegiance (bayat) to al Qaeda leader Ayman al Zawahiri.

A Julani and HTS loyalist known as Abu Abdullah al-Shami defended the moves in late 2017. Abu Abdullah conceded that when the matter was referred to al-Adel and Abdullah, the pair rejected Al Nusrah’s repositioning. Abu Abdullah argued that he and his colleagues had the right to reject their decision, because they “are in an enemy state (Iran),” where “they are being held there against their will.”

But another al Qaeda veteran, Abu al Qassam (a former deputy to Abu Musab al Zarqawi), rejected this argument, explaining that the al-Adel and Abdullah “left prison and they are not imprisoned,” as HTS’s Abu Abdullah had claimed. Instead, the two al Qaeda managers “are forbidden from traveling until Allah makes for them an exit and they move around and live their natural lives except for being allowed to travel.”

“The term confined means they are in prison,” or something similar that prevents them from independently exercising their “will,” Abu al Qassam wrote. But this wasn’t the case, “so be aware…that this should not be a reason on challenging their decisions.”

In other words, Abu al Qassam argued that HTS’s men were wrong to reject the decision issued by al-Adel and Abdullah, because while they were inside Iran (and prevented from traveling abroad due to security concerns at the time), they were still free to operate.

It is likely that the controversy surrounding the formation of HTS — and Abu al Qassam’s claim that al-Adel and Abdullah “are not imprisoned” inside Iran — played a role in the State Department’s decision to increase its reward for the pair.

Indeed, the newly-released UN report says al Qaeda’s “leaders in the Islamic Republic of Iran,” specifically Abdullah and al-Adel, have countered “the authority of” Abu Muhammad al-Julani, by “causing formations, breakaways and mergers of various Al Qaeda-aligned groups in Idlib.” Since earlier this year, al Qaeda-linked groups have broken away from HTS, or announced their presence once again after a sustained absence.

Despite these problems, however, the UN finds that “HTS and its components still maintain contact with al Qaeda leadership.”

Pointing to the controversy in Syria as evidence of their influence, the UN says al Qaeda’s “leaders in the Islamic Republic of Iran have grown more prominent, working with” Zawahiri” and “projecting his authority more effectively than he could previously.”

And now the bounties for each of them is $10 million.

*Note: This article was updated after its initial publication to include information from a newly-released UN report. That report confirmed the analysis in the article — that is, the UN confirmed that the two al Qaeda leaders, al-Adel and Abdullah, are operating inside Iran.

This article has been adapted from several previous reports published by FDD’s Long War Journal. For additional details on al-Adel, Abdullah and related issues, see:

Analysis: Al Qaeda’s interim emir and Iran, May 18, 2011

Senior al Qaeda leaders reportedly released from custody in Iran, Sept. 18, 2015

CIA releases video of Hamza bin Laden’s wedding, Nov. 1, 2017

Analysis: Ayman al Zawahiri calls for ‘unity’ in Syria amid leadership crisis, Dec. 2, 2017