Note: This article was originally published by The Weekly Standard.

Ashraf Ghani, the president of Afghanistan, announced June 7 that his government’s forces would unilaterally enter into a ceasefire with the Taliban until June 20. It remains to be seen how the Taliban responds. The jihadists didn’t agree to the plan beforehand and may simply use the lull in fighting to plan the next wave in their nationwide assault on the government. Ghani and his American backers are hoping for something much more. They think there is a chance the Taliban’s men will lay down their arms. General John Nicholson, who oversees the U.S. war effort, quickly endorsed Ghani’s move, calling it a “bold initiative for peace” and saying he supports “the search for an end to the conflict.”

But the ceasefire isn’t “bold”; it is desperate and delusional. The more we listen to America’s military commanders the clearer it becomes that they do not understand the enemies they face. Nor do they have a realistic plan for victory.

The current strategy hinges on the idea that the Taliban will tire of the fight, especially since President Trump decided, somewhat surprisingly, to stay in it last year. With several thousand more troops, the military argued, they could train enough Afghans to push back the insurgents and make them abandon their relentless jihad. Nearly 10 months later, we know that is not even close to true. According to our estimates, approximately 60 percent of Afghanistan’s districts are either contested or controlled by the Taliban. The jihadists outright control at least 10 percent of the districts. But fully half of Afghanistan is contested terrain, with the two sides vying to claim the ground as their own.

The United States and its Afghan allies have thus not beaten back the jihadists in the months since the Trump administration announced its new strategy last August. They have, at best, prevented them from conquering even more ground. Why would the Taliban, which is not close to being defeated, give up now?

Ghani’s ceasefire was first proposed by the Afghan Ulema Council (AUC), a religious body of up to 3,000 figures from throughout Afghanistan who support the government. Earlier this week, the AUC ruled that suicide bombings were religiously impermissible and the ongoing Afghan jihad is illegal. Naturally, the Taliban rejected both findings out of hand, declaring that the AUC’s announcement was nothing more than American propaganda. Furthermore, the Taliban warned “religious scholars” they should “fear for their end in this and in the next world for considering the critical issue of righteous jihad as illegitimate.” Those are not the words of a group looking to make peace.

In praising Ghani’s announcement, Nicholson cited a February 14 “open letter” from the Taliban to the American people as evidence that the group is serious about negotiating peace. He has even gone so far as to claim that the Taliban “outlined” the “elements of a peace proposal” in the missive. It does not require a close Straussian reading of the text to see that the Taliban did no such thing. The jihadists merely offered to negotiate the terms of their own victory.

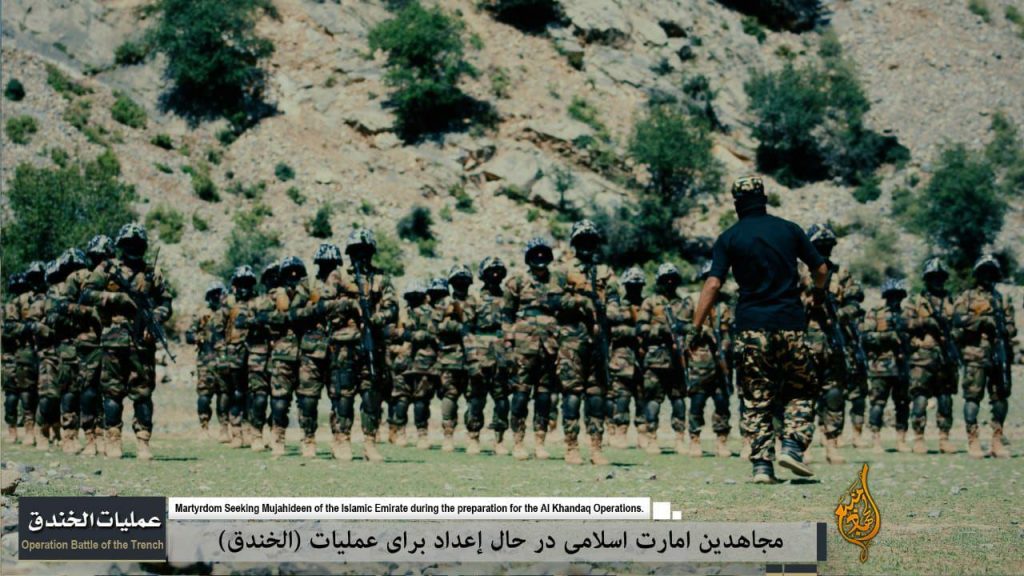

As in other statements, the Taliban demanded an end to “foreign occupation,” stressing it is the Afghans’ “legal, religious and national obligation” to fight the Americans until they are gone. The Taliban blasted the Afghan government as an illegitimate, “corrupt regime,” while accusing anyone who works with it of “committing treason against our nation and national interests.” The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan—that is, the Taliban’s authoritarian regime—is the only true “representative of its people” and a “regional power with deep roots which cannot be subdued by sheer force.”

So much for the idea of getting the Taliban to participate in a unified political entity—the central goal of the peace talks envisioned by the Afghan government and its American allies. The Taliban will not compromise on the central reason for its existence: the resurrection of its Islamic emirate. The only “plan” offered by the Taliban is this: We win, you lose. No other reading of the February 14 letter is plausible — one has to be seriously confused to think it represents anything close to a pathway to peace. The Taliban even blames the United States for the rise in the Afghan opium trade, despite the fact that the Taliban itself is the main beneficiary of this illicit trafficking.

There are other reasons to be skeptical. The Obama administration’s attempts to negotiate with the Taliban ended in a fiasco. The United States made various concessions—for example, allowing the Taliban to open a political office in Qatar and removing some Taliban figures from international terrorist designation lists—but received nothing in return. Many Taliban leaders remain safely ensconced in Pakistan, where they are under no immediate threat. And the Taliban refuses to forswear al Qaeda, as the United States has begged the organization to do for years.

Perhaps Ghani’s gambit will somehow bear fruit. Given this sordid history, however, we wouldn’t count on it.

7 Comments

Why can’t the Yanks say they and their ally, Afghanistan have lost the war, rather than call the ceasefire ‘requested’ by the puppet government, for Ramadan, a ‘ bold action’.

What do you suggest then as an alternative course of action?

“cease fire” guess we could all use a good joke about now!

I doubt Gen. Mattis believes the Taliban will lay down their weapons. To me this seems like a blunt proposition to the Taliban who are also fighting for their lives and territory against ISISK. Stop attacking GiROA, and we will stop dropping bombs on you, and instead focus that effort against our common enemy (ISISK).

This is a political strategy, not military. Remember that elections are coming. Ghani looks good, tries to do the right thing. If the taliban attack he looks like a person doing the right thing and the country’s resolve will strenghten

.

Quite frankly, I despise losers. I have no sympathy for losers. Like they say in the Navy, “Loose lips sink ships.” All they are doing is ‘teleprompting’ weaknesses. If anything, this will make it more dangerous and (hopefully not) more deadly for our troops and their legitimate Afghan partners. This may only serve to embolden the enemy. This is just appalling.

We should ask people like Nicholson (and Gilani), “If you couldn’t handle the job, then why did you take it?” They need to be sacked (i.e., replaced). If they can’t say anything worthwhile about the situation, then they shouldn’t be allowed to say anything at all.

I know for a fact that with the right strategy this situation in Afghanistan can be completely turned around in at most 3 years. It all hinges on the opium trade. But if you’ve got a bunch of quitters running things over there, then at a minimum they need to be replaced.

Bin Laden chose Afghanistan to base his operations against the West wisely since the supply routes for foreign forces run through either Iran, Russia or Pakistan and at this moment none are both available and reliable to support a large enough force to secure the country. At low cost, all three of those non-allies of the US can tie down US personnel, equipment and cost the US treasury much more than they have to expend backing the Taliban behind the scenes. We will not risk confrontation with nuclear powers like Iran or Russia to secure supply lines sufficient to maintain a force adequate to defeat the Taliban and secure all of Afghanistan. We do seem willing to do something to stop Iran’s nuclear threat to the world and their creeping threat to control the Middle East oil supply which would allow an economic extortion of the West. If we do enough to keep an allied government going in Afghanistan, long enough to deal with Iran one way or another, perhaps another alternative approach to this Gordian knot will present itself down the road. If we have to remove the current Iranian regime and see it replaced with a friendlier one to resolve the much bigger problem Iran presents than is presented by the Taliban, a much different situation with new possibilities may become available.