At the height of its power, AQAP held large public rallies.

On May 23, a new jihadist propaganda outfit, Al-Badr Media Foundation, announced its presence online.

Al-Badr’s stated mission is to buttress the “supporters of Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula” (AQAP). The media shop offered four ways it hopes to do this, saying that it will: “dispel” the alleged “suspicions and rumors” spread about the mujahideen by the “Crusaders” and AQAP’s Muslim ideological opponents; expose the “lies” of the Arab and “Western media in their war on the mujahideen”; disseminate the call to jihad and incite the Muslim youth to “join the caravan of jihad…in the Arabian Peninsula”; and increase “security awareness” among the jihadists’ rank and file, as well as their supporters, while encouraging them to counter the infidels in the media.

Al-Badr’s first release the following day, May 24, was intended to serve the last cause. Via its Telegram channel, the group released a pdf file containing a series of tweets by Muhannad Ghallab, an AQAP mouthpiece. The short statements are tips on how to avoid America’s drones and other security measures, which is unintentionally amusing given that Ghallab himself was killed in a US drone strike in 2015. Therefore, either Ghallab didn’t heed his own advice, or it wasn’t sufficient.

Left unsaid in Al-Badr’s first releases is the real reason for its existence: AQAP’s media arms have suffered significant losses. The US and its allies have repeatedly targeted the personnel responsible for producing AQAP’s videos, statements and publications, including the English-language Inspire magazine and the Arabic-language Al Masra newsletter. This campaign has been waged for years, but has continued in recent months.

In Dec. 2017, US Central Command (CENTCOM) reported that “[o]ngoing operations pressuring” AQAP’s “network” had “degraded” its “propaganda production, reducing one of the methods for the terror group to recruit and inspire lone wolf attacks across the globe.” At the time, CENTCOM pointed to the fact that Al-Masra Newsletter, which was “previously published three times a month,” had “not been published since July.” Al-Masra has been sidelined since then, too. AQAP’s main propaganda arm, Al-Malahim Establishment for Media, has suffered from disruptions as well. And a senior AQAP propagandist known as Abu Hajar al-Makki was killed in an airstrike the same month as CENTCOM’s announcement.

The setbacks for AQAP’s propaganda efforts likely affect al Qaeda’s global network. Although Al-Masra described itself as “independent,” FDD’s Long War Journal repeatedly assessed that it actually served as a central clearinghouse for information and commentary on al Qaeda’s worldwide efforts. Much of Al-Masra’s content focused on issues far outside of Yemen, including events everywhere from West Africa to South Asia. Tellingly, the publication contained key windows into the thinking of the al Qaeda’s senior leadership on crucial issues affecting the jihad.

This assessment was confirmed by CENTCOM, which described Al-Masra as an AQAP publication. In January, an expert report on al Qaeda and the Islamic State published by the United Nations Security Council further confirmed this analysis. The authors of the report, who belong to the UN’s “Analytical Support and Sanctions Monitoring Team,” similarly emphasized that Al-Masra was “one of the leading outlets in which leaders of” al Qaeda’s “core,” AQIM, AQIS, and Shabaab were “interviewed and announced attacks.” Indeed, the UN concluded that AQAP “continues to play a leading role in the propaganda activities of the al Qaeda core,” with member states finding “that AQAP in Yemen serves as the communications hub for the entire al Qaeda organization.”

Therefore, it stands to reason that the disruptions in AQAP’s messaging capabilities have ramifications outside of Yemen’s borders.

This is true despite the fact that Ayman al Zawahiri and other senior al Qaeda figures continue to record and disseminate messages on a regular basis. Thus far, al Qaeda’s senior leadership in South Asia has not produced a weekly Arabic newsletter similar to Al-Masra, nor a regular English-language pamphlet such as Inspire. For instance, the English-language magazine produced by al Qaeda’s senior leadership, Resurgence, was short-lived and never achieved Inspire’s broader distribution online.

Despite setbacks, UN finds al Qaeda and AQAP to be “resilient”

Regardless of the setbacks suffered by AQAP’s media arms, the UN’s expert report concluded that the “global al Qaeda network has remained resilient” and “poses a greater threat than” the Islamic State “in several regions.” One of these regions encompasses the Arabian Peninsula. “Despite the current difficulties of AQAP,” according to the UN’s member states, the Islamic State “in Yemen remains weaker than AQAP.” Still, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s operation has grown inside Yemen, even as it has lost ground elsewhere, so this assessment should be frequently reconsidered. The Islamic State frequently produces and disseminates media related to its activities in Yemen, including photos and videos.

Since 2014, al-Baghdadi’s self-declared caliphate has outpaced the al Qaeda network when it comes to international terrorist attacks. But the UN warned that AQAP “continues to plot external attacks,” including a July 2017 plot against Jordan that was “disrupted.” That failed plot was planned by Khalid Batarfi, an AQAP “deputy.” FDD’s Long War Journal has previously argued that Batarfi is likely a senior member of al Qaeda’s international management team, as both his rhetorical and operational roles are indicative of a global portfolio.

AQAP has taken a number of steps that are intended to help the group survive the “sustained military pressure” it faces, according to the UN’s report.

Al Qaeda has long sought to integrate its men into Yemen’s tribal infrastructure. It is not entirely clear how fruitful this effort has been, but the UN warned that “AQAP leaders and fighters are strengthening their ties with Yemeni tribes and families, in many cases through marriages.” Although they don’t advertise their governance efforts as frequently as their rivals in the Islamic State, AQAP’s men are “conducting and financing social activities to demonstrate its governing and humanitarian capabilities to the Yemeni community.” AQAP is also “trying to avoid clashes with local tribes,” while “selling weapons” and ammunition to tribesmen and “arms dealers” to make up for financial shortfalls. Such arms transfers supplement other “income streams,” such as “bank robberies, kidnapping for ransom and extortion.”

The UN’s experts found that AQAP has also reorganized its hierarchy after losing “many of its field commanders and a significant number of its fighters.” The goal of these moves is to “expand its influence and gain more recruits.”

According “to Member State information” received by the UN, AQAP emir Qasim al-Raymi appointed a jihadist known as Abdullah Mubarak to serve as the group’s “new sharia official.” Mubarak is described as “a Yemeni national and graduate of Iman University in Sana’a.”

Iman University was founded by Shaykh Abd-al-Majid al-Zindani, a Muslim Brother-linked ideologue who was also one of Osama bin Laden’s early allies. AQAP has benefited greatly from Zindani’s support through the years, so it is not surprising that an Iman graduate is now one AQAP’s most senior sharia officials. The UN reported that Mubarak replaced Ibrahim al-Rubaysh, a former Guantanamo detainee who was killed in a US drone strike in Apr. 2015. It is not clear why Mubarak was named as Rubaysh’s successor more than two years after the latter’s death. It is possible that someone else temporarily filled the position.

As part of its reorganization, AQAP has also “appointed a number of new ‘emirs’ in different regions.” They report to the organization’s “military commander,” a jihadist known as Ammar al-San’ani. The UN reported that these regional “emirs” and other AQAP operatives are “using encrypted instant messaging applications and wireless equipment,” which has been given to the “owners of safe houses.”

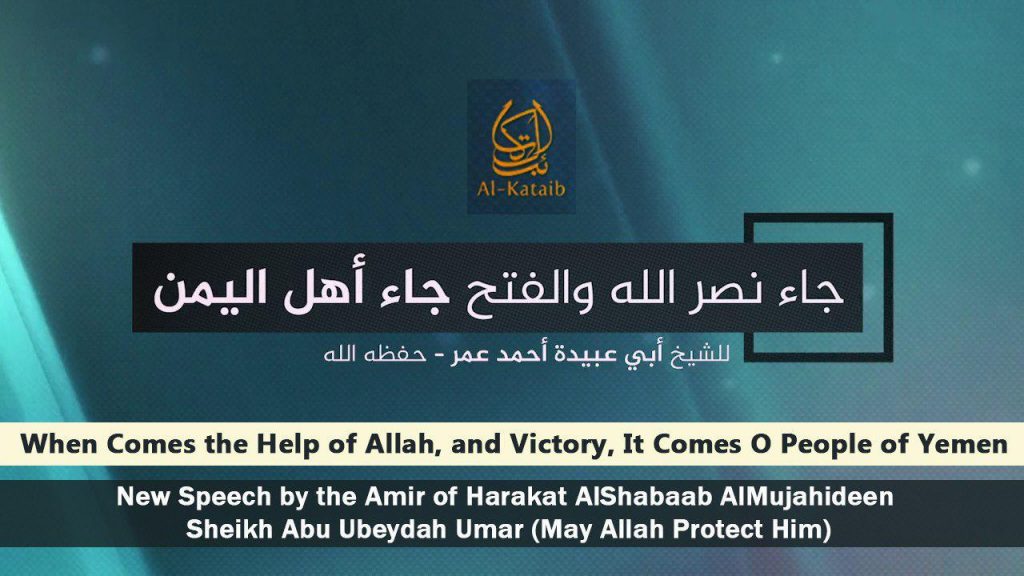

Shabaab’s emir seeks to boost morale in Yemen

Abu Ubaydah Ahmad Umar, the emir of Shabaab (al Qaeda’s branch in East Africa) has sought to boost AQAP’s morale in recent weeks. On May 1, Shabaab released a message from Abu Ubaydah titled, “When Comes the Help of Allah, and Victory, It Comes O People of Yemen.” [See FDD’s Long War Journal report, Analysis: Shabaab advertises its al Qaeda allegiance.]

Abu Ubaydah knows that AQAP faces stiff resistance on multiple fronts, but he urged its men to carry on, portraying the mujahideen’s hardships as a divine test.

“The purpose of your jihad,” Abu Ubaydah said, is to force all of the “occupying” powers “from your land,” including the House of Saud, the “apostate” United Arab Emirates (UAE), the “rejectionists” (meaning Shiites and specifically the Iranian-backed Houthis), as well as the “apostate American agent” President Hadi. This is a “difficult” task, Abu Ubaydah conceded, but he implored his “mujahideen brothers” to increase their offensive operations by staging “ambushes,” “implanting mines,” conducting assassinations, and deploying “martyrdom-seeking operations” against the enemies’ defensive positions. He advised that protracted “guerrilla wars” are a great benefit to the “oppressed,” because they “drain” the enemy.

Abu Ubaydah also told his “mujahideen brothers in Yemen” to “stand by your leaders” and abide by their decisions, while avoiding those who spread “gossip” or “stir up sedition.” Similarly, Al-Badr Media now says that it will attempt to “dispel” the “rumors” circulating among the jihadists.

Abu Ubaydah’s words likely carry weight within AQAP, as Shabaab has long conspired with its fellow al Qaeda branch.

In 2011, for instance, a Shabaab fighter named Ahmed Warsame was captured while returning to Somalia from Yemen. Warsame subsequently pleaded guilty to a number of terror-related charges. The Department of Justice explained that Warsame was a Shabaab “soldier” as of 2009, but he also acted as an emissary to AQAP. Warsame “brokered a weapons deal, arranging for al Shabaab to purchase weapons directly from AQAP” and, in 2010 and 2011, also received “weapons, explosives, and other military-type training from” AQAP. Warsame intended to share AQAP’s explosives training with other Shabaab members “when he returned to Somalia,” but he was captured before he could do so.

This type of cooperation across the Gulf of Aden continues to this day. According to the UN’s report in January, the “movements of foreign terrorist fighters, couriers and individuals performing logistical tasks between Somalia and Yemen continues.” Their “movements are facilitated by former [Shabaab] fighters who relocated to Yemen and are active in AQAP.”

The UN provided another interesting tidbit on Shabaab’s operations, noting that while Abu Ubaydah’s men “initially pursued a plan to eliminate foreign terrorist fighters that came to Somalia from outside the immediate region to join” Baghdadi’s Islamic State, the group “more recently” has been “welcoming foreign terrorist fighters whose skills and knowledge are essential in training their fighters.” The foreigners “serve temporarily as trainers and leave once the transfer of knowledge, capabilities and skills is accomplished.” The authors of the UN report concluded that Shabaab remains stronger than the Islamic State in Somalia, just as al Qaeda’s arm in Yemen remains the top dog among Sunni jihadists.

A multi-sided war in Yemen

Like their jihadi cousins in northwestern Syria, AQAP’s leaders and members are confronted by a complex, multi-sided war that tests both their resolve and skill. Evaluating AQAP’s prospects requires a careful assessment of many factors, from the role of foreign actors to the strength of the group’s tribal ties. It is often difficult to assess these variables. But it is easy to see that the US-led effort to disrupt AQAP’s media capabilities has had a significant effect. Otherwise, there would be no need for Al-Badr Media, which is the latest in a series of AQAP-affiliated propaganda efforts.

Al Qaeda’s senior leaders in South Asia have rebuilt As Sahab, their main media arm. Today, they frequently produce timely messages. AQAP continues to produce some propaganda as well, but not nearly as often as during the group’s peak output. Key jihadi publications such as Inspire and Al-Masra have been disrupted. It remains to be seen how AQAP and al Qaeda’s senior leadership will attempt to rectify this gap.

1 Comment

If 10% of what is wasted in Afghanistan (80% of the money is wasted.) is actually INVESTED into Africa to fight groups like al qeada. How much better off would everyone be including Afghanistan?