The Islamic State has revoked one of its most problematic and extreme religious rulings. The one-page repeal was disseminated on social media sites associated with the so-called caliphate on Sept. 15. It was issued after months of controversy surrounding the group’s approach to declaring takfir on other Muslims, a key ideological issue.

On May 17, the Islamic State’s delegated committee, which answers to Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, issued a finding titled, “That Those Who Perish Would Perish Upon Proof and Those Who Live Would Live Upon Proof.” The ruling quickly proved to be contentious because of its broad approach to takfir, the practice of declaring other Muslims to be non-believers due to their supposed apostasy or heresy. The Islamic State and its predecessors have always relied on a wide-ranging definition of takfir, even as compared to their jihadist rivals in al Qaeda and the Taliban. But the May 17 pamphlet took the issue further, apparently removing the little flexibility that Baghdadi’s men had previously afforded most Muslims.

In the months since it was first issued, the ruling exacerbated an ongoing crisis within the Islamic State’s leadership, leading to its repeal.

In a one-page memo disseminated online, and addressed to all of the Islamic State’s “provinces” and other internal entities, the group explains that the May 17 document was riddled with factual errors and “caused conflict and division specifically among the ranks of the mujahideen and generally among Muslims.”

The self-declared caliphate said its followers should consult the texts issued prior to the disruptive document, as these books, after being amended and edited, “do not contain anything that contradicts the doctrine of the people of sunnah.”

“We advise” returning to and relying “on these books for clarification of the issue of excommunication of polytheists [mushrikin], the ruling of the abstaining community [meaning those who refuse to implement sharia], and the rulings on houses or other issues,” the Islamic State’s leadership commanded in the Sept. 15 memo.

The short document is a remarkable admission. The Islamic State has implicitly conceded that its delegated committee, one of the most powerful councils within the self-declared caliphate, has made a grave doctrinal error.

The delegated committee within the so-called caliphate’s structure

The Islamic State promoted the role of the delegated committee in a July 2016 video titled, “The Structure of the Khilafah.” The production emphasized the key jobs performed by the delegated committee on behalf of Baghdadi.

“The task of communicating orders once they’ve been issued and ensuring their execution is delegated to a select group of knowledgeable and upright individuals with perception and leadership skills, as the Khilafah cannot himself personally carry out the work of the state, for that is an impossible endeavor,” the video’s narrator explained. “So it’s necessary for there to be a body of individuals that supports him [Baghdadi] and that body is the delegated committee.”

The delegated committee has broad administrative powers. The narrator explained that it “supervises” the wilayat (provinces), the dawawin, and the “offices and committees.” Each “province” is led by a wali (governor) who “refers serious matters to the delegated committee” and “governs the wilayat’s subjects.”

The dawawin are “places for protecting rights and are under the supervision of the delegated committee.” There are 14 dawawin, which are supposed to have physical offices in every wilayat. These offices “assume the maintenance of public interests” and “protect the people’s religion and security.” The dawawin are tasked with their own broad range of responsibilities, ranging from the arts of soldiery to dawa (proselytizing) and religious guidance.

The committees and offices are “concerned with various matters” and are “comprised of specialized personnel,” all of whom are “supervised by the delegated committee.” The committees and offices oversee: the arrival of “those who emigrate” to the lands of the caliphate, the staffing of the various dawawin, the affairs of Muslim prisoners, research of sharia issues, the wilayat outside of Iraq and Syria, and tribal relations, among other duties.

Therefore, according to the Islamic State’s own explanation, the delegated committee has vast power within the organization.

Earlier this month, a statement attributed to this same body encouraged the Islamic State jihadists fighting in Hama province to stand firm against Bashar al Assad’s regime and its allies. The authors of this memo, which was also disseminated on social media accounts, said that Baghdadi (the “Emir of the Faithful”) was “pleased” with the fighters’ “perseverance” in Hama. That is, assuming the memo is authentic, the delegated committee still speaks for Baghdadi.

Another memo attributed to the delegated committee earlier this year prohibited Islamic State fighters from using social media sites. The memo explained that the group’s enemies were reportedly exploiting these channels for intelligence purposes.

Problems caused by May 17 ruling previously explained by analysts

It is not surprising that the May 17 ruling was voided, despite the fact that it was heavily promoted in the Islamic State’s online newsletters. For instance, both Al Naba (an Islamic State newsletter published in Arabic) and Rumiyah (an online magazine published in multiple languages) promoted versions of the delegated committee’s ruling, even as controversy over its contents raged within the Islamic State.

The problems caused by the delegated committee’s ruling were previously discussed at length by other analysts.

Writing for the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point in June, Bryan Price and Muhammad al-`Ubaydi concluded that the May 17 document, along with the aforementioned social media ban imposed on the caliphate’s rank and file, indicated that “the group is suffering from command and control and other related operational authority problems.”

In August, R. Green of The Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI) published a lengthy analysis of the May 17 ruling and the “intense internal dispute” that followed. In “Dispute Over Takfir Rocks Islamic State,” Green explained that some of the Islamic State’s most senior ideologues objected to the order.

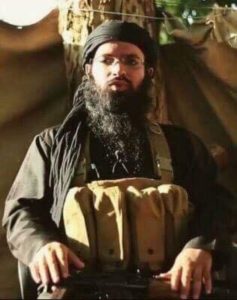

Among them was Turki al-Bin’ali (pictured on the right), who was killed in an airstrike in Mayadin, Syria just two weeks after the document was issued. Al-Bin’ali was one of the earliest and most important jihadist ideologues to support Baghdadi’s caliphate-building project. He helped poach jihadists from al Qaeda and its branches around the globe, often drawing the ire of some of his fellow ideologues and one-time comrades. But the May 17 memo went too far for Al-Bin’ali, who served as the Islamic State’s “Grand Mufti.”

Al-Bin’ali wrote a letter, translated by MEMRI, in which he offered 20 objections to the ruling. He complained that it was issued with “the second most important seal” in the Islamic State, meaning the delegated committee, which is directly “subordinate” to Baghdadi. Al-Bin’ali said that “extremists” were celebrating the declaration. Green explained that Al-Bin’ali’s objection stemmed from his concern that the declaration would lead to an “endless chain of takfir.”

The most extreme members of the Islamic State not only wanted to declare takfir on the mushrikin, or polytheists, which is a common practice for the organization, but also any Muslims who failed to similarly condemn the mushrikin. This means that even if a Muslim committed no sin himself, he could be denounced by the jihadists as a disbeliever simply for failing to condemn other alleged sinners.

The delegated committee appeared to leave little to no wiggle room on the issue. “Those both far and near know that the Islamic State…has not ceased for a single day from making takfir of the mushrikin [polytheists], and that it treats the making of takfir of the mushrikin as one of the utmost principles of the religion, which must be known before knowing the prayer and other obligations that are known of the religion by necessity,” the delegated committee wrote in its May 17 memo. (Emphasis added.)

For Al-Bin’ali, this and other language in the memo made it sound like there is no ambiguity on the issue of takfir, despite the fact that even the Islamic State’s hardline clerics had previously allowed that there was at least some uncertainty. As Green noted, Al-Bin’ali argued that the delegated committee’s logic would lead the Islamic State to denounce as unbelievers even legendary jihadist figures such as Abu Musab al Zarqawi (the founder of al Qaeda in Iraq, which evolved into the current Islamic State) and Abu Muhammad al Adnani (the Islamic State’s spokesman), both of whom justified the slaughter of Shiite Muslims and other “polytheists,” but refrained from declaring takfir on all Muslims who did not follow their ways.

In other words, not even a savage like Zarqawi went as far as the delegated committee, which greatly expanded the number of Muslims who could be labeled as disbelievers. If the delegated committee’s logic was followed to its necessary end, then even fewer Muslims would be left out of the Islamic State’s ring of the damned.

The Islamic State has always been a highly exclusive and notoriously extreme organization. This was true well before the delegated committee’s May 17 order. Incredibly, however, the delegated committee found a way to outflank even infamous ideologues such as Al-Bin’ali.

Al Qaeda newsletter publishes alleged dissent by Islamic State sharia official

Al Qaeda, the Islamic State’s rival, has sought to capitalize on the problems caused by the delegated committee’s May 17 memo. In July, an issue of Masra* newsletter carried an article that described the objections of an alleged Islamic State sharia official known as Khabbab al-Jazrawi. He lamented that “extremists” had taken over the delegated committee and complained that its members lack the proper religious credentials to issue such a fatwa, which effectively declared takfir on whole Muslim nations.

In its May 17 memo, the delegated committee chastised those Muslims who “refrain from making takfir of those who vote with the claim of their being ignorant of the reality of elections.” That is, the delegated committee rejected ignorance as an excuse for refraining from the excommunication of Muslims who participate in elections.

Al-Jazrawi countered this and other arguments in the May 17 document by noting that previous leaders, such as Zarqawi and Abu Omar al Baghdadi, did consider ignorance to be valid excuse for those who violated the group’s sharia law by participating in elections. Similarly, al-Jazrawi argued that the delegated committee had gone too far in declaring other Muslim scholars to be infidels. Al-Jazrawi claimed that some went so far as to discuss whether Ibn Taymiyyah, a medieval ideologue who is widely respected in jihadi circles, was really an infidel.

Al-Jazrawi addressed Baghdadi directly, warning the supposed “Caliph” that he would answer to Allah for allowing the delegated committee to become so extreme. Al-Jazrawi also hinted that former Baathists from Saddam Hussein’s Iraq had become too powerful within the Islamic State, implying that they were using the delegated committee to enhance their personal power.

While al Qaeda has its own reasons for highlighting al-Jazrawi’s alleged critique, there are multiple indications that the May 17 document had caused, or inflamed, leadership conflicts within the self-declared caliphate.

The retraction on Sept. 15 concedes as much.

*Although Masra claims to be an “independent” publication, it often carries messages from senior al Qaeda leaders and conveys their thinking on various political and ideological issues. FDD’s Long War Journal assesses that Masra also acts as a clearinghouse for “news” and opinions from various al Qaeda actors around the globe.

1 Comment

Very scholarly article.

I like it when these guys get dead.

Don’t care that much about their propaganda.

Do you think the Russians got Baghdadi on May 28?

It feels like it to me because they killed his cleric friend and locked up his wife.