On Mar. 30, the US Treasury Department designated Bahrun Naim, a senior Islamic State figure from Indonesia, as a terrorist. It was the latest in a series of US government designations targeting the self-declared caliphate’s network in Southeast Asia.

Naim absconded from his home and made his way to the self-declared caliphate’s stronghold in northern Syria in either late 2014 or early 2015 — just months after Abu Bakr al Baghdadi’s followers declared him “Caliph Ibrahim.”

Naim, a computer guru who once worked at an internet café, had spent a short stint in prison after being convicted on illegal weapons charges in 2010. He developed a number of suspicious relationships with extremists, especially in his home city of Solo on the island of Java. Naim was also once a member of Hizbut Tahrir, which seeks to resurrect the Islamic caliphate, but abstains from overt acts of violence. According to Voice of America, a spokesman for Hizbut Tahrir claimed that Naim was expelled from the group when it was discovered that he was in possession of a gun.

Still, Naim was mainly a minor irritant for local authorities before his departure for Syria.

More than two years later, Indonesian authorities and allied governments throughout Southeast Asia are hunting Naim’s recruits, attempting to stop potentially dozens of men and women from killing in the name of the caliphate.

The 33 year-old Naim may be half a world away in Raqqa, Syria, but he has been able to lead his followers via social media applications. Using Telegram and possibly other apps, Naim provides aspiring terrorists in his home country with bomb-making advice and also helps them select targets to attack. He has been one of the most prolific planners of the Islamic State’s so-called “remote-controlled” attacks – even if, to date, most of his operations have been thwarted.

Naim isn’t just abusing social media applications such as Telegram. He has also reportedly made use of Paypal and bitcoins to bankroll terrorist operations, according to the Straits Times.

In its designation, Treasury noted that Naim “reportedly organized and funded” the Jan. 14, 2016 attack in Jakarta. Four people were killed and 23 more injured that day. The damage could have been far worse, as a team of several terrorists from the Islamic State’s local branch coordinated suicide bombings and shootings in the heart of a civilian shopping area. It appears the suicide team wasn’t very well-trained, otherwise the death toll would have been higher.

Naim has assembled teams of jihadists throughout Indonesia by relying on his personal rolodex of extremists. And he has augmented this network through his prolific use of social media. There is no question that encrypted messaging apps make Naim’s job easier, but his in person ties to a web of Indonesian extremists are no less important. It is this combination of Naim’s pre-existing relationships in his home country and the ease with which he can communicate online that has caused headaches for counterterrorism officials.

The Jakarta attack is a case in point. While Naim’s digital hand was detected in the planning of the operation, other jihadist figures inside Indonesia were also instrumental.

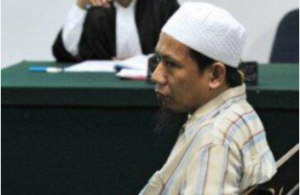

One of them is a radical cleric named Oman Rochman (also known as Aman Abdurrahman), who has long known Naim. Rochman (pictured on the right) has been imprisoned in Indonesia since 2010, yet he directed the Islamic State’s operations inside the country for months after Baghdadi’s caliphate declaration in the summer of 2014. Rochman was convicted on terrorism-related charges stemming from his support for a camp run by Jemaah Islamiyah, an al Qaeda-affiliated group. Al Qaeda is opposed to the Islamic State – vehemently so. However, as Abu Bakr al Baghdadi’s cause began to mushroom in the summer of 2014, the Indonesian jihadist scene split between the two rival camps. Rochman went the way of the so-called caliphate.

Treasury designated Rochman as a terrorist in January, describing him as the “de facto leader for all [Islamic State] supporters in Indonesia.” From behind bars, Rochman has played a prominent role in recruiting for the group’s operations abroad, personally blessing the travels of some new recruits and even requiring them “to obtain a recommendation from him before departing for Syria.” He has acted as the “main translator” in Indonesia for the Islamic State’s propaganda, disseminating the organization’s media throughout the country. And he “issued a fatwa (decree) from prison in Jan. 2016 encouraging Indonesian militants to join” Baghdadi’s enterprise.

Rochman worked with still another US-designated terrorist, Tuah Febriwansyah (also known as Muhammad Fachry), to build the Islamic State’s organizational capacity inside Indonesia. Jemmah Anshorut Tauhid (JAT) was one of the many Indonesian extremist groups affected by the rise of Abu Bakr al Baghdadi’s enterprise and its global competition with al Qaeda. In mid-2014, according to Treasury, JAT “leaders sought Febriwansyah’s support to bolster JAT during a schism over allegiance to” the Islamic State. Officials credit Febriwansyah and his comrades with recruiting “as many as 37 Indonesians on behalf of” the so-called caliphate. Febriwansyah was arrested on March 21, 2015, but that hasn’t stopped other Islamic State converts from continuing with their business.

For instance, Rochman “authorized” the Jakarta operation from behind bars, according to Treasury. Just weeks beforehand, he ordered one of the terrorists responsible “to carry out [Islamic State] attacks in Jan. 2016.” Thus, Rochman provided a veneer of religious authority for the targeting of innocent civilians. Indonesian authorities may have finally grown wise to Rochman’s scheming last year and placed him in a higher security facility, thereby limiting his contact with outsiders. Regardless, the threat posed by the Islamic State’s local network remains virulent.

The muscle for the Jakarta plot came from Jamaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD), which was designated as a terrorist organization by the State Department in January. After the Islamic State’s caliphate declaration in 2014, a large number of Indonesian jihadists rushed to declare their allegiance. Confusion ensued over which group would represent Baghdadi’s cause. Thus, as Foggy Bottom reported, Jamaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD) was created in 2015 as an umbrella organization for “almost two dozen Indonesian extremist groups that pledged allegiance to [Islamic State] leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.” Rochman’s hand guided the process.

JAD provides Naim with a base of supporters ready to carry out his bidding. Not only did Naim fund the JAD men responsible for the assault on Jakarta, he has transferred large sums of cash to fuel his broader plans, which he unfurled almost immediately upon his arrival in Syria.

In its March 30 designation, Treasury noted that Naim orchestrated a series of failed plots beginning in 2015. In August of that year, Naim “reportedly instructed three men in Solo, Indonesia to plan a bomb attack of a police post, a church, and a Chinese temple.” Around that same time, he “provided instructions and funding to an Indonesia-based associate for the purpose of establishing and training a bomb-making cell.” Authorities disbanded the cell, but Naim didn’t give up on the idea of establishing a bomb-making unit capable of doing his bidding. He simply “called on other associates to form a new cell,” which he also funded.

Naim’s plots, relying on JAD operatives, have kept coming in the months since.

Reuters counted at least 15 “foiled” attacks and “more than 150” terror-related arrests in Indonesia during 2016. Not all of these plots were directly tied to Naim, but at least several of them, including the most significant ones, were.

In Aug. 2016, Indonesian police raided one Naim’s cells on Batam island. His minions reportedly intended to fire rockets at Singapore’s Marina Bay, which is just 10 miles or so across the waterway. Marina Bay is an especially affluent area, with high-end shopping, a busy casino, a massive ferris wheel and all of the other types of locales one would expect well-to-do travelers to frequent. Members of the Batam cell “were in direct contact with Bahrun Naim in Syria and he had ordered them to attack Singapore and Batam,” National Police Chief Tito Karnavian told reporters at a press conference, according to Reuters.

Members of the Batam crew, like many of Naim’s other accomplices, were put out of work in short order. But the cat-and-mouse game that authorities and Naim are playing is deadly serious. Of particular concern is Naim’s expertise in crafting sophisticated explosives. He is transferring his know-how to followers inside Indonesia and potentially elsewhere. And it isn’t just men who are volunteering for Naim’s schemes. He is also luring women into his designs, describing them as terror “brides.”

Last November, Indonesian authorities discovered a terror cell that reportedly had ambitious plans to strike several targets at once during the holiday season, including the parliament. According to the Straits Times, the Islamic State loyalists had obtained “military-grade explosive material such as TNT and RDX” in such large quantities that it could have caused “twice the damage done in the 2002 Bali bombings,” which were carried out by the aforementioned Jemaah Islamiyah. To put the matter in perspective: More than 200 people were killed in the Bali bombings, yet Indonesian officials think the Islamic State’s men were building a bomb twice as deadly.

Then, last December, Indonesia’s elite counterterrorism force – Detachment 88 – detected a cell of several jihadists who were planning to bomb Jakarta’s presidential palace.

“This is a new (terrorist) cell and they had learned to make bombs from Bahrun Naim using the Telegram messaging (smartphone) application,” Colonel Awi, an Indonesian official, explained. The Straits Times again drew attention to the explosives involved, reporting that the recovered bomb was “more powerful than military-grade TNT,” with a police official adding it “could destroy anything within a radius of 300” meters.

The Islamic State’s Indonesian men reportedly intended to have a woman, Dian Yulia Novi, deliver the bomb. Novi’s newfound husband was in on the plot. And authorities discovered her “martyrdom” letter to her parents. Time magazine profiled Novi in early March (“ISIS Unveiled: The Story Behind Indonesia’s First Female Suicide Bomber“). Naim recruited her husband, Nur Solihin, and also told him to find a “bride” capable of carrying out an operation. Solihin was already married to another woman, Time reported, but he added Novi as a wife in order to comply with Naim’s directions.

According to the Associated Press and other press outlets, Novi subsequently confessed that Naim had ordered her to strike a popular changing of the guard ceremony at the palace.

Once again, Telegram was Naim’s preferred means for communicating with his followers back home. “I had been communicating with him for three days, yes, via Telegram,” Novi allegedly admitted, according to ABC. “He told me which target to bomb, the Presidential Palace Military Guards.”

Abu Muhammad al-Indonesi

Naim isn’t the only Indonesian Islamic State leader in Syria whose reach extends all the way back into his homeland.

Bachrumsyah Mennor Usman (also known as Abu Muhammad al-Indonesi) leads Katibah Nusantara (KN), an Islamic State unit based in Syria that is comprised of fighters from Indonesia, Malaysia and other Southeast Asian countries. (Naim has been a leading figure in KN as well.)

The US Treasury sanctioned Usman along with Rochman in January. Some recent reports claim that Usman may have been killed while fighting Bashar al Assad’s forces near Palmyra, Syria. But Usman’s demise has not been confirmed and jihadist death reports are often wrong.

Usman is a former student of Rochman’s and also one of the Islamic State’s most prolific recruiters of Southeast Asian fighters.

In 2014, Usman starred in an eight-and-a-half-minute video titled “Join the Ranks,” in which he gave a typical caliphate vs. the world speech. A screen shot from the video can be seen above. He called on the “brothers in Indonesia” to “pledge allegiance to Emir ul-Mu’minin [‘Emir of the Faithful’], Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi,” saying that he and his comrades had seen “with our own eyes that the Islamic State implements the Sharia of Allah in the entire land.” In addition to portraying Baghdadi’s project as a jihadist utopia, Usman stressed that the Islamic State was fighting Shiites and Bashar al Assad’s regime, among its numerous other foes. The Islamic State showcased Indonesian and Malaysian children training with weapons in another video starring Usman that was produced in early 2015.

Even before he relocated to the lands of Baghdadi’s caliphate in early 2014, Usman claimed to represent the group’s cause inside Indonesia. Like Naim, he built a web of extremist contacts. Treasury describes Usman’s network as an “underground movement” that was exposed only after “Join the Ranks” became a must-watch video for jihadists. Usman not only drew recruits to Syria, he also began to orchestrate plots inside his abandoned home country.

Usman transferred as much as $105,000 to a unit known as the “Bekasi cell,” which began plotting against Indonesian targets, according to Treasury. He “ordered an associate to plan attacks similar” to the Jakarta operation and also “transferred funds” to the Philippines. Although Usman’s digital trail isn’t as publicly pronounced as Naim’s, it is logical to assume that he is also using encrypted messaging apps and other online tools to carry out his business.

Plots inside Malaysia

Authorities are confronting a similar, albeit less numerous, stream of threats in nearby Malaysia.

A Malaysian jihadist named Muhammad Wanndy Bin Mohamed Jedi, better known as “Wanndy,” was designated on the same day as Naim. Like his Indonesian counterpart, Wanndy has been using Telegram’s encrypted chat application to direct terror in his native country.

Treasury noted that Wanndy “claimed responsibility on behalf” of the Islamic State for the June 28, 2016 “grenade attack on a nightclub in Malaysia in which eight people were wounded.” The nightclub assault may have been the first successful operation by Baghdadi’s followers in Malaysia. But it wasn’t the only plot Wanndy has attempted to remote control.

In March 2016, Treasury reported, “Malaysian authorities arrested a cell of 15 Malaysia-based militants who were subordinate to Wanndy” and supported the Islamic State’s operations in Syria. Investigators found that Wanndy had ordered some of its members “to conduct attacks in Malaysia.” Wanndy has “threatened to assassinate the Malaysian Prime Minister” and other “top officials” as well.

Returning foreign fighters and the ongoing threat

Counterterrorism officials fear that as the Islamic State continues to lose ground in Iraq and Syria, more foreign fighters will return to their native countries with bad intentions. This is possible, but the group is not close to defeat. Naim, Usman, Rochman and Wanndy have recruited hundreds of fighters for the Islamic State’s Malay-speaking unit, the KN. Those who do not die as the caliphate loses control over some of its territory, or participate in the insurgency that follows, could very well attempt to lash out back home. However, the Islamic State’s international network already has a significant footprint in Southeast Asia.

Tito Karnavian, the Indonesian police chief, has said that Naim seeks “to unite all [Islamic State] supporting elements in Southeast Asia, including Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines.” Karnavian added that countries throughout the region should cooperate against this common threat, “because it is not home-grown terrorism, it is part of the [Islamic State] network.”

Chances are that Naim won’t live to see the day when a caliphate rises in Southeast Asia. Although he has numerous potential co-conspirators waiting to assist his cause, they are not currently overwhelming the region’s security forces. In the meantime, however, Naim and his followers are probing for weaknesses in Indonesia’s counterterrorism defenses. Islamic State operatives have “remote-controlled” plots in Europe and elsewhere. They have also attempted to do the same inside the US. Naim is employing this same tactic. And his ability to use Telegram for communicating with jihadists in Indonesia and elsewhere helps the Islamic State maintain cohesion across its Southeast Asian network.

In a blog post published in late 2015, Naim praised the Islamic State’s assault on Paris. If Naim got his way, that attack, which shut down a Western capital, would be replicated in Jakarta or elsewhere in the region. Thus far, Indonesian officials have thwarted Naim’s more sinister designs. But there are no guarantees that will continue to be the case in the future.

Note: The picture of Bahran Naim included above was originally published by Reuters.