|

|

|

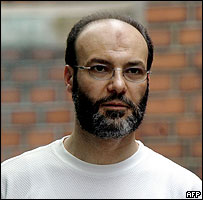

Al Qaeda operative Mamoun Darkazanli ran the notorious Al Quds Mosque in Hamburg, Germany. AFP photo. |

On Monday, German authorities announced that they closed down the Taiba mosque in Hamburg. The mosque achieved infamy as home to several of the 9/11 plotters under its previous name — Al Quds.

The name change did not stop the mosque from continuing to serve as a meeting ground for Islamist extremists and terrorists. Thus, the Germans, who along with other Western intelligence agencies had been monitoring the mosque for years, decided it needed to be shuttered.

This is not surprising. Western intelligence agencies have suspected since the 1990s that the imam in charge of the mosque, Mamoun Darkazanli, is one of al Qaeda’s top operatives in Europe.

Darkazali was one of the first suspected al Qaeda figures to have his accounts frozen by the US Treasury Department and the United Nations following the September 11 attacks. He had established a lengthy dossier by then. Despite being a known extremist with a plethora of terrorist ties, however, Darkazanli has avoided a lengthy prison sentence.

German laws have consistently gotten in the way of bringing Darkazanli to justice.

According to Congress’s “Joint Inquiry Into the Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001,” a report prepared by the House and Senate Intelligence Committees, Darkazanli first popped up on the CIA’s radar in 1993. The US intelligence community investigated the imam after “a person arrested in Africa carrying false passports and counterfeit money was found with Darkazanli’s telephone number.” The Joint Inquiry found: “A CIA report notes that, despite careful scrutiny of Darkazanli and his business dealings, authorities were not able to make a case against him.”

Ironically, this same year (1993), Darkazanli purchased a ship for Osama bin Laden. Published reports say that Darkazanli bought a ship named “Jennifer” for al Qaeda’s CEO.

Darkazanli would garner attention within the US intelligence community again in the late 1990s. The FBI “became interested in Darkazanli in 1998,” the Joint Inquiry found, “after the arrests of Wadi El-Hage and Abu Hajer, operatives in Bin Ladin’s network.”

El Hage served as bin Laden’s personal secretary, managing the terror master’s vast rolodex. “According to FBI documents, Darkazanli’s fax and telephone numbers were listed in El-Hage’s address book,” the Joint Inquiry reported. El-Hage was convicted by a US court for his involvement in al Qaeda’s 1998 embassy bombings.

Abu Hajer al Iraqi (whose real name is Mamdouh Mahmud Salim) is one the founding members of al Qaeda and he, too, resides in a US prison. (During his time in custody, Abu Hajer stabbed a prison guard in the eye, blinding him.) Abu Hajer was arrested in Germany in 1998 and extradited to the US.

When the FBI investigated Abu Hajer’s finances, the Joint Inquiry notes, the Bureau “discovered that Darkazanli had power of attorney over a bank account belonging to Hajer, a high-ranking al-Qa’ida member who has served on its Shura Council.”

In other words, Darkazanli was so well-regarded within the terror network that he was tasked with managing a top al Qaeda leader’s bank account.

Darkazanli worked with his fellow Syrian, Mohammed Zammar, in Germany for years. And the two forged close ties to some of the 9/11 hijackers. Just months after the FBI began investigating Darkazanli’s ties to Abu Hajer, Darkazanli’s links to the future hijackers raised another red flag.

“In March 1999,” the Joint Inquiry’s report reads, “CIA received intelligence about a person named ‘Marwan’ who had been in contact with Zammar and Darkazanli. Marwan was described as a student who had spent time in Germany ”

Only after the September 11 attacks did the CIA figure out that “Marwan” was Marwan al-Shehhi – one of the 9/11 hijackers.

This is likely just a sampling of what the FBI and the CIA knew about Darkazanli and Zammar prior to September 11. The Joint Inquiry’s report reads:

“CIA and FBI counterterrorism operations and investigations prior to September 11, 2001 repeatedly produced intelligence relating to two individuals in Hamburg, Germany – Mamoun Darkazanli, a suspected logistician in Bin Ladin’s network, and Mohammed Zammar, a suspected recruiter for al-Qa’ida.”

If US authorities “repeatedly produced intelligence” on the pair prior to September 11, then why was nothing done? The Joint Inquiry’s report says that German laws were a major hindrance.

“Considerable pressure was placed on foreign authorities in the years leading up to the September 11 attacks to target Darkazanli, Zammar, and other radicals,” the Joint Inquiry found. In fact, the “Joint Inquiry reviewed numerous documents describing efforts to pressure [REDACTED] authorities to act” but “these efforts were largely unsuccessful.”

It does not take much reading between the lines to figure out that the “foreign authorities” in question were the Germans. The very next paragraph reads:

“Significant legal barriers restricted Germany’s ability to target Islamic fundamentalism. Before September 11, it was not illegal in Germany to be a member of a foreign terrorist organization, to raise funds for terrorists, or plan a terrorist act outside German territory. A legal privilege also dramatically restricted the government’s ability to investigate religious groups. The German government apparently did not consider Islamic groups a threat and were unwilling to devote significant investigative resources to this target.”

The Joint Inquiry noted that German “law has since been changed.” With respect to the September 11 attacks, it was too little, too late. The Hamburg cell could plot the deadliest terrorist attack in history from German soil and, according to German law at the time, this was not illegal.

Incredibly, German law would interfere with the prosecution of Mamoun Darkazanli once again after the September 11 attacks. Spanish officials launched their own investigations into al Qaeda’s operations in Europe. Unsurprisingly, they found that Darkazanli was a major player.

Spanish authorities found that Darkazanli was closely tied to Imad Yarkas, the head of al Qaeda’s presence in Spain and one of the top al Qaeda leaders in all of Europe prior to his arrest and conviction. They also found that Darkazanli had wired funds to Mustafa Setmariam Nasar, one of al Qaeda’s chief ideologues.

Darkazanli was so high up in al Qaeda that Spanish Judge Baltasar Garzon deemed him al Qaeda’s “chief financier” and “permanent interlocutor and assistant” to Osama bin Laden in Europe.

Spain indicted Darkazanli for his al Qaeda role and wanted to try him. The Germans initially detained Darkazanli while he awaited extradition. Ultimately, the German high court determined that the EU arrest warrant issued by Spain contravened the German constitution. There would be no trial in Spain.

Darkazanli was set free.

Spanish officials and the FBI learned something else about Darkazanli. The Joint Inquiry explains:

“After September 11, the FBI discovered that Darkazanli traveled to Spain in the summer of 2001 at approximately the same time that [lead hijacker Mohammed] Atta was there. It is possible that Darkazanli and Atta met with Yarkas, who may have had advance knowledge of the September 11 attacks. Spanish authorities intercepted a call to Yarkas on August 27, in which he was told, ‘we have entered the field of aviation and we have even slit the throat of the bird.’ The FBI speculates that the ‘bird’ represented the bald eagle, symbol of the United States. Yarkas, who was arrested by the Spanish on November 13, 2001, has met at least twice with Bin Ladin. A Spanish indictment alleges that he had contacts with Mohammed Atta and Ramzi Bin al-Shibh.”

The meeting referenced above remains one of the great unsolved mysteries of the September 11 attacks. Ramzi Binalshibh, the point man for the September 11 attacks, met Atta in Spain in July 2001. The meeting is remarkable, mainly because Atta had to leave the US at a key juncture in the 9/11 plot – just two months before his day of terror. By leaving American soil, Atta was taking a big risk. It was possible that intelligence officials in Europe or the US would become suspicious of his movements.

Why did Atta have to make this trip? We do not know for sure. And, as it turned out, Atta made the trip back and forth over the Atlantic unnoticed. Who did Atta meet with, exactly? Again, we do not know for certain.

The 9/11 Commission found that while US “authorities have not uncovered evidence that anyone met with Atta or Binalshibh in Spain, Spanish investigators contend that members of the Spanish al Qaeda cell were involved in the July meeting and were connected to the 9/11 attacks.”

And as explained by the Joint Inquiry, Mamoun Darkazanli is also suspected of attending the meeting.

This raises the possibility that there was more to Atta’s trip to Spain than even the 9/11 Commission learned. And it raises the possibility that Mamoun Darkazanli was directly involved in the 9/11 plot.

As it stands, American officials (cited by the 9/11 Commission and the Joint Inquiry) believe that Darkazanli’s “close associate,” Mohammed Zammar, helped recruit al Qaeda’s suicide hijack pilots. Darkazanli’s role has been left open-ended – no one is apparently sure whether or not he played a direct role in the 9/11 plot even though there are many good reasons to suspect he did. Darkazanli had a close relationship with the Hamburg cell and Zammar; it seems inconceivable that he wouldn’t know what they were about to do.

According to some reports, Darkazanli was even responsible for funding the Hamburg cell.

In any event, after all these years German officials have decided that Darkazanli’s recruiting days at the Al Quds/Taiba mosque should come to an end – at least for the time being.

There is no telling what Darkazanli will do next. He has avoided justice before.