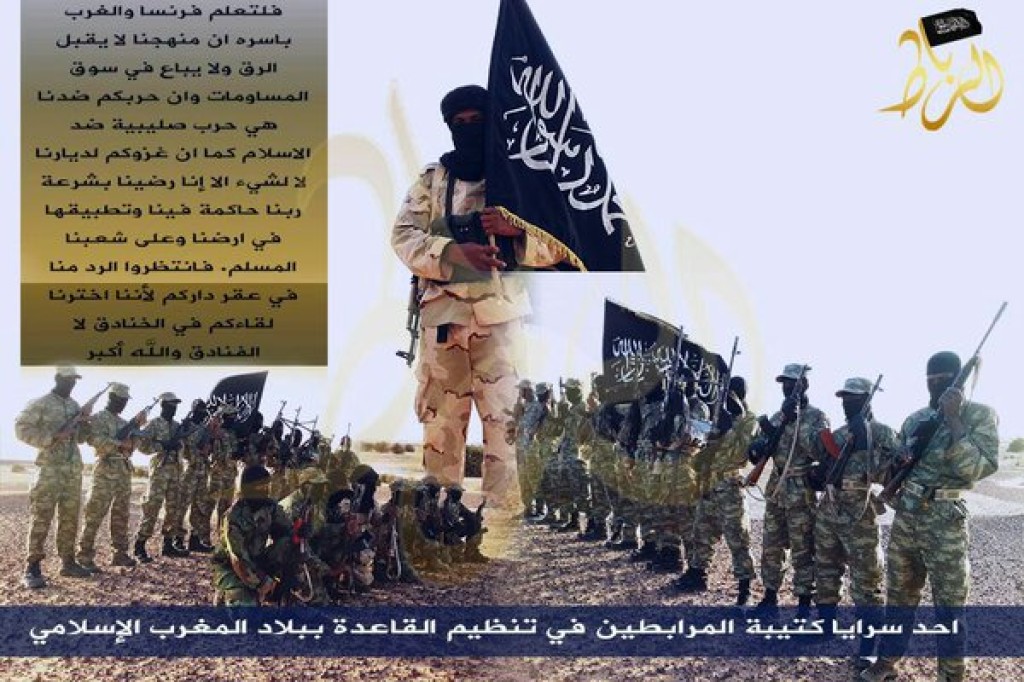

Photo released by Al Murabitoon and Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb showing “one brigade of Katibat al Murabitoon.”

French special forces, as part of the counterterrorism mission Operation Barkhane, conducted a raid in northern Mali over the weekend targeting the jihadist group Al Murabitoon. According to the French Ministry of Defence, the raid “neutralized 10 terrorists,” with “neutralized” usually serving as a euphemism for killed.

The statement read, “On the night of 19 to 20th December, French forces conducted an operation in the region of Menaka in Mali against affiliated elements of the terrorist group Al Murabitoon.” It goes on to explain that the jihadist group is “responsible for a number of attacks against the Malian and Nigerien populations, local armed forces, and international forces.” The Ministry of Defense said when fighting ended, after nearly four hours, “two pickups and a dozen motorcycles were seized” along with “a significant amount of arms and explosives.”

Earlier this year, French special forces also killed two Al Qaeda leaders in northern Mali, although the French military did not say where.

The town of Menaka, which is in the Gao Region, has long been within Al Murabitoon’s area of operations. In 2012, the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO), one of Al Murabitoon’s constituent groups, took over the town of Gao before being kicked out in the 2013 French intervention. In April, Al Murabitoon launched a suicide assault on the nearby town of Ansongo, killing three civilians and wounding 16 others including nine Nigerien peacekeepers.

On Dec. 11, 2014, French special forces killed Ahmed al Tilemsi, the emir of MUJAO, in a raid in Gao. Gilles Jaron, a French Army spokesman, said a dozen terrorists, including Tilemsi, were “neutralized” in a midnight raid. “Following an intelligence opportunity,” Gilles said, “French forces led an operation in the Gao Region in coordination with the Malian authorities.” [For more on Tilemsi and his death, see LWJ report, French troops kill MUJAO founder during raid in Mali.]

Al Murabitoon was formed in 2013 from the merger between Ahmed al Tilemsi’s MUJAO and Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s Al Mulathameen Brigade and swore allegiance to Al Qaeda emir Ayman al Zawahiri. After being led by an Egyptian commander, Al Tilemsi took over as emir of Al Murabitoon until his death. In July, the group’s Shura Council confirmed it elected Mokhtar Belmokhtar as its overall emir. However, some members in the MUJAO side of the group defected to the Islamic State, but it is not known how many. In addition to conducting several attacks in the Gao region and a hotel siege in central Mali, Al Murabitoon has also conducted several attacks in Mali’s capital of Bamako this year.

The attacks included an assault on a Malian nightclub, which killed five people, an attempted assassination of a Malian general, and an attack on UN troops. It also claimed last month’s raid on the Radisson Blu hotel in Bamako. The jihadist group, which sent two fighters to conduct the attack, killed more than 20 people after taking over 100 people hostage in the siege.

The assault on the Radisson Blu heralded the reintegration of Al Murabitoon into Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). On Dec. 4, AQIM’s Al Andalus Media released an audio statement from Abdelmalek Droukdel, the emir of AQIM, announcing the merger of Al Murabitoon into its ranks. The same statement also said that the Bamako attack was the first joint assault carried out by the two groups.

In addition to attacks in Mali, Al Murabitoon has conducted attacks throughout the Sahara. The jihadist group was behind the January 2013 suicide assault on the In Amenas gas facility in southeastern Algeria, and the May 2013 suicide assaults in Niger which targeted a military barracks and a uranium mine. Scores of people were killed in these attacks.

Despite France’s intervention in Mali in early 2013 and current counterterrorism mission in the region, al Qaeda and its allies continue to launch regular attacks. More than 50 UN peacekeepers have been killed in Mali since 2013, making it one of the most dangerous UN missions in the world. [See this map of Al Qaeda-linked attacks in Mali since 2014 made by The Long War Journal for more information.]

1 Comment

Hi Andy,As always, thknas for your comment (btw, not sure if you saw, but I did respond to your comment on my Algeria piece for TAP). I am writing this on the fly, so sorry if it is a bit scattershot.All of the information you mentioned in your first paragraph jives with what I’ve read in international and local press, as well as what I am hearing from people in the area and various analysts. That said, the situation doesn’t seem particularly strange to me. There have been reports of seizures of illicit fuel in southern Algeria in recent months. But I can’t help thinking that if Algeria really wanted to kill the Islamist project in northern Mali stone dead, they could simply close the economic supply lines that keep the region alive. I can’t say I know much about the feasibility of shutting down the Algerian/Malian border, but it seems like it would be a monumental undertaking and assumes that the Algerian state, in all of its internal contradictions and dysfunctions, is capable of simply cutting off the economic supply lines. And then there’s that elephantine question: where are the armed groups in the north getting their money from? I know that they earned millions from kidnapping, and took kickbacks from the drugs trade, but keeping two thirds of Mali going with hardly any tax revenue, and maintaining ever-growing militias must be a hugely costly business. And there hasn’t been much kidnapping or probably much drug revenue since January. So who funds the armed groups? Just curious, what leads you to the conclusion that the drug trade has subsided since January? Similarly, MUJWA did net a huge chunk of cash in July from hostage payments, and we really don’t know how much cash these groups have on hand and who is funding them. You are right to say that we can’t let the questions concerning external funding/support hang eternally, but as you’ve said elsewhere, this is frustratingly beyond journalism at this point. Qatar, Morrocco, Algeria have all been listed a possible culprits, but I’m not sure why commentators are limiting the conjecture to nation-states and their governments. As for Ag Ghali, I don’t mean to imply that he isn’t a very important figure and that he was not instrumental in opening the door (if not orchestrating) the Islamist takeover of northern Mali. I largely agree with your assessment of why young Tuaregs would have initially joined his cause. My only point is that I think people might be overstating the amount of operational control that Ag Ghali has in northern Mali. There are all sorts of rumors about his actual power and influence these days, and it is not at all clear to me that Ansar Dine is simply his personal militia. The nature of these groups, their structure, their memberships and their relationships with one another are incredibly fluid. Any efforts to co-opt, turn or buy-off Ag Ghali need to take into consideration these realities. One final note, while I think it is useful and helpful to draw on your personal experience in Kidal (just as I call upon my time living in Gao to inform my writing), I think commentators need to be very careful in using terms such as the ordinary Tamashek mindset. At the end of the day, this is a stereotype, and though it is a positive one, it is not qualitatively different from polemicists who refer to the Arab mind when talking about the lack of democracy in the middle east. I share your belief that the ideologies being espoused by these Islamist groups are probably unappealing to the vast majority of northern Malians, but I am not willing to go so far as to say Tuareg culture makes its young people immune to these ideologies.* Various forms of fundamentalist Islam, for whatever reason, have proven capable of undermining and subverting traditional cultural systems in many places and among different cultures. While it breaks my heart to think that some northern Malians now find this ideology appealing, I don’t want to over-privilege my personal experiences (and sources) in the region so as to dismiss outright the reports trickling out of the north.* I can recall several villages in the Gao region where very conservative Islam had become common practice and many of these villages self-identified as Wahabbi. They were by no means hostile to foreigners (some hosted Peace Corps Volunteers), but I think we need to be careful when we talk about “Malian Islam” as a uniform concept. These were Malians, who were expressing their faith in a way that might not have been indicative of how most Malians practice it, but that doesn’t make their practice “foreign.”Best,Peter