On Dec. 20, the Defense Department announced the transfer of four Afghans from Guantanamo to their home country. All four had been previously approved for transfer by President Obama’s Guantanamo Review Task Force.

It is often reported that detainees, such as the four transferred to Afghanistan, have been “cleared for release.” The implication is that they had been “cleared” of any wrongdoing and their release is risk-free. But this is not true. The task force recommended that all four be transferred subject to “appropriate security measures” being enacted by the host country. That is, the task force expected that whichever country took the four Afghans, the local government would take steps to ensure that they did not pose a threat. In practice, such security measures are often non-existent.

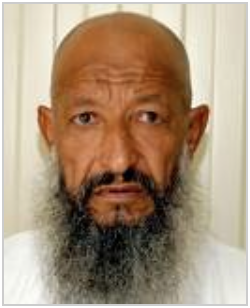

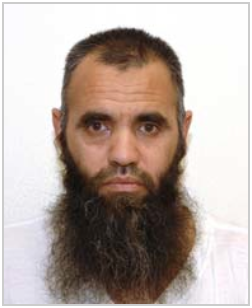

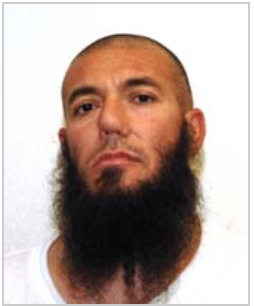

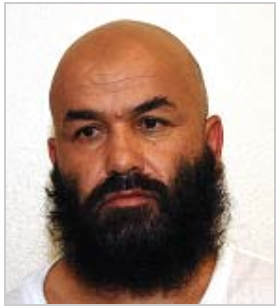

Joint Task Force Guantanamo (JTF-GTMO), which oversees the detention facility, assessed the four Afghan detainees years earlier. The secret JTF-GTMO threat assessments for the four detainees — Mohommod Zahir, Khil Ali Gul, Abdul Ghani, and Shawali Khan — were authored in 2008 and subsequently leaked online.

In each case, JTF-GTMO deemed the detainee to be “high risk,” who “is likely to pose a threat to the US, its interests, and allies.” JTF-GTMO recommended that all four remain in the Defense Department’s custody.

Three of the JTF-GTMO threat assessments also begin with a warning: “If released without rehabilitation, close supervision, and means to successfully reintegrate into his society as a law-abiding citizen, it is assessed detainee would probably seek out prior associates and reengage in hostilities and extremist support activities.” Only the file for Zahir does not include this language.

JTF-GTMO’s warnings were rooted in intelligence showing that all four now former detainees had been involved in insurgency activities against the US and coalition partners. Each detainee was suspected of either serving in a leadership position, or directly reporting to jihadists who did. At least two of them have been tied to members of the so-called “Taliban Five,” a group of senior Taliban leaders who were transferred from Guantanamo to Qatar earlier this year. [See LWJ report, Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl exchanged for top 5 Taliban commanders at Gitmo.]

Mohommod Zahir (internment serial number 1103) is “assessed to be a veteran high-level member of the Taliban Intelligence Directorate,” according to JTF-GTMO. He is “also assessed to be a weapons smuggler in the Ghazni Province and has possible ties to Afghanistan narcotics trafficking.” Zahir “is associated with senior members of the Taliban intelligence and other Taliban officials and Anti-Coalition (ACM) members including Jalaluddin Haqqani.” As of 2008, when JTF-GTMO’s threat assessment was written, Zahir’s associates still held “considerable influence in current Afghan affairs.”

The JTF-GTMO threat assessment for Zahir contains descriptions of the files and other evidence recovered in his residence. The materials were key to JTF-GTMO’s understanding of Zahir’s role.

Some of the documents contained “names and telephone numbers of associates including senior Taliban officials.” The “[n]ames and numbers included senior Taliban such as ministers and ACM commanders such as Jalaluddin Haqqani,” and listed “contacts within Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, the US, and Russia.”

Zahir’s “notebooks included names, phone numbers, commodities purchases and coordination such as sugar with mention of selling in Washington and mention of Britain, Brazil, Ukraine among others.” JTF-GTMO’s analysts surmised that the “movement of food and materials noted in the contents of this document appears to be outside the scope of an intelligence official, but could be consistent with an international trading business or modernization programs and possibly includes code for heroin.”

A memo found in Zahir’s “pocket litter” is addressed to the Taliban’s Internal Affairs Ministry Department of Intelligence, and Zahir is identified as the “Chief of Intelligence” in the memo. A second memo found in Zahir’s “pocket litter” is signed by “Mullah Mohammad Zahir, Secretary General, Directorate of Intelligence,” which was assessed to be Zahir. The second memo is addressed to “His Excellency, Deputy of Economic Affairs, Council of Ministers” and discusses “flights to Saudi Arabia for the annual hajj.”

Two “Codan high-frequency (HF) radios” were found in Zahir’s home, and JTF-GTMO found this “is unusual for the general Afghan population.” However, “Taliban leaders were known to use this equipment” and, in April 2000, Mullah Omar “ordered the collection of all the Codan vehicle radio systems,” which were then redistributed “to fifty-two key leaders in the Taliban.”

Authorities also found a fax that connected Zahir to the Taliban’s intelligence chief, Qari Ahmadullah. In the fax, the “Iranian News Agency” requested Ahmadullah’s assistance in providing Osama bin Laden with interview questions related to the 9/11 attacks. JTF-GTMO found that “[n]o direct association” between Zahir and bin Laden had been made, but Zahir’s possession of the fax and other documents indicated a “high level of access or trust with” Ahmadullah.

Zahir’s career with the Taliban, as recounted by JTF-GTMO, included relationships with various senior jihadists. “After the Taliban gained control of the Ghazni Province in 1997,” the JTF-GTMO file reads, Ahmadullah instructed Zahir “to travel with the President of the Security Police, Muhammad Ibrahim, to Kabul…to work in the headquarters of the Taliban Intelligence Directorate.” JTF-GTMO identified “Muhammad Ibrahim” as Jalaluddin Haqqani’s brother, Muhammad Ibrahim Haqqani.

At one point, Zahir allegedly worked as a “cook and security guard” for the Taliban’s director of logistics, and Zahir’s boss “reported directly to Abdul Haq Wasiq,” the Taliban’s deputy minister of intelligence. Wasiq is a member of the so-called “Taliban Five,” a group of senior Taliban leaders transferred from Guantanamo to Qatar earlier this year. JTF-GTMO also described Zahir as Wasiq’s “subordinate.”

Intelligence cited by JTF-GTMO connected Zahir to additional Taliban leaders, including other detainees once held at Guantanamo. DNA tests revealed that Zahir and Gholam Ruhani, who was transferred from Guantanamo to Afghanistan in 2007, “are related and possibly siblings.” Ruhani is “an admitted Taliban Intelligence member” and was the “head of Taliban operations and security in Kabul.”

JTF-GTMO also found that Zahir worked as an “investigator” for Mohamed Rahim, a senior Taliban intelligence official who was transferred from Guantanamo to Afghanistan in December 2009. The threat assessment for Rahim references debriefings during which Zahir identified Rahim as the deputy director of logistics in the Taliban’s intelligence ministry. Zahir claimed to US officials that he “worked closely” with Rahim and “knew him from childhood.” Rahim and Zahir were both captured on July 18, 2003 in Afghanistan, perhaps together. Rahim also worked underneath Abdul Haq Wasiq in the Taliban’s hierarchy.

The JTF-GTMO file contains references to Zahir’s possession of uranium, which, if true, is remarkable. Zahir “was arrested on suspicion of possessing weapons including Stinger missiles and uranium, which detainee’s recovered documents indicate was intended for use in a nuclear device.” US forces recovered “a small sealed can marked, in Russian, ‘Heavy Water – U235 150 Grams’,” the JTF-GTMO file reads. It is not clear if this was really uranium, some other substance, or simply a ruse.

During his combatant status review tribunal (CSRT) and administrative review board (ARB) hearings, Zahir tried to distance himself from the Taliban. “I have never been associated with [the Taliban],” Zahir claimed during his CSRT. During the hearings at Guantanamo, Zahir first claimed that he never worked for the Taliban’s intelligence ministry, but eventually admitted that he was forced to work as a cook, even though he supposedly didn’t know which Taliban department he was working for.

Zahir was confronted with the fax, discovered in his residence, from the Iranian News Agency requesting assistance from Qari Ahmadullah, the Taliban intelligence chief, in getting a series of 9/11-related questions to bin Laden. “I am not aware of the fax,” Zahir claimed during one hearing. “I am not aware of Qari Ahmadullah,” he continued. “I admitted to these things because in Bagram they beat us with a cable until we admitted to them. I was beaten. I am not aware of anything. I was a teacher and they brought me to this job.”

But the officer who presided over Zahir’s hearing quickly pointed out that the evidence concerning Ahmadullah’s fax “does not refer to something” Zahir admitted, but to “something that was found on you.” In other words, the allegation regarding the fax is not tied to any alleged confession by Zahir. When asked to describe his supposed beating, Zahir quickly blamed “a tribe in central Afghanistan” that looks Asian. Members of this tribe supposedly “covered their faces and beat” Zahir. It is clear from the transcript that Zahir’s story was not something well-documented, and appears to have been a diversion.

JTF-GTMO concluded that Zahir was in fact a senior Taliban official. Zahir’s jihadist career began during the war against the Soviets in the 1980s.

Khi Ali Gul (ISN 928) was “a member of an Anti-Coalition Militia (ACM) group named Union of Mujahideen (UOM) with indirect ties to the Haqqani Nework,” according to JTF-GTMO’s analysts. Gul “was a member and probably [a] leader” of his ACM group, which “conducted an attack against US forces.” On Dec. 1, 2002, Gul and “several other Afghans met at his house to plan and execute a rocket attack against” an American base. Later that same day, “six rockets were fired at” the base. Weeks later, Gul was captured by Afghan military forces and quickly transferred to US custody.

JTF-GTMO concluded that Gul held senior leadership roles within the jihadists’ ranks during the Taliban’s regime and thereafter. Gul “reportedly served as an intelligence chief under the Taliban regime during which he harassed and assassinated Afghan intellectuals,” the JTF-GTMO file reads. After the Union of Mujahideen was disbanded, Gul allegedly became an “intelligence officer” in something called the “Gorbaz Mehdi Jihadi Battalion.” Many members of this battalion had “ties to known Taliban and/or al Qaeda personnel.” While serving in the battalion, Gul “routinely collected information on Afghans who helped US and Coalition forces.”

JTF-GTMO found that Gul had a number of other suspicious ties. He “is an associate of Mohammad Nabi Omar,” who is one of the so-called “Taliban Five” leaders transferred to Qatar earlier this year. An Afghan military officer identified Gul as “an agent for the ISID of Pakistan.” (There is no other detail in the JTF-GTMO file explaining Gul’s possible role as a Pakistani agent, however.) And JTF-GTMO found that Gul’s “brother remains active in ACM activity.”

During his combatant status review tribunal (CSRT) at Guantanamo, Gul denied any wrongdoing. He claimed that he was part of the Karzai government up until his capture and even said he protected sleeping Americans during the battle of Tora Bora.

Gul used colorful language to deny holding any leadership role within the jihadists’ ranks, saying that just as you “cannot cover the sun with two fingers” you can’t hide the identity of a commander in Afghanistan. And no one knew him as a leader, Gul claimed. Gul argued that he did not work for, or against, the Taliban in Afghanistan, and he denied any connection to Jalaluddin Haqqani. Gul also disputed reports that he had met with Osama bin Laden.

The only role Gul admitted to playing was fighting the communist regime in Afghanistan before it fell to the mujahideen in the 1990s. “I didn’t fight directly with Russians [during the jihad against the Soviets],” Gul claimed. “Inside the government, I fought against the communists that were in Afghanistan.” During an administrative review board hearing, Gul elaborated: “Yes, I have done jihad. In my province there were no Russians. There was a communist, [our] own communist, and I was fighting them. When the Russians/Soviet Union pulled out of Afghanistan I stopped being in touch with [any groups]. I had no connection with [any] other groups. When such party or each group started fighting each other, I had nothing to do with them.”

JTF-GTMO clearly did not believe Gul’s story, concluding that he remained an active leader until his capture in late 2002.

Abdul Ghani (ISN 934) was once charged before a military commission, but the charges were dismissed. This does not indicate that authorities believed the charges were erroneous, as detainees have escaped prosecution in the commission system, which has been plagued by delays and legal challenges, for a variety of reasons.

According to the commission charge sheet, Ghani attacked US forces in Afghanistan in late 2001 and 2002. He allegedly transported and planted “land mines and other explosive devices…for use against US and coalition forces” and “fired rockets at US forces and bases.” He was also accused of shooting and wounding an Afghan soldier.

Ghani allegedly cooperated with al Qaeda in executing the attacks. “In or about 2002,” the charges read, “Abdul Ghani accepted monetary payments, including payments from al Qaeda and others known and unknown, to commit attacks on US forces and bases.”

Additional information concerning Ghani’s past can be found in a leaked JTF-GTMO threat assessment. Ghani “has a history of involvement with the Taliban military forces and Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin (HIG) prior to the 11 September 2001 attacks.”

During his time in US custody, Ghani “admitted he was involved in at least one rocket attack on US forces at the Kandahar, [Afghanistan] airport in 2002 and is assessed to have launched multiple attacks against US and Coalition forces in Afghanistan.” Multiple sources “have independently report[ed] his involvement in at least four other attacks against US forces using rockets and possibly mines.”

JTF-GTMO also concluded that Ghani was a member of a “40-man Taliban-aligned militia unit established…to conduct assassinations, kidnappings, and ambushes of US and Afghan officials and military forces.”

A close reading of the file for Ghani reveals that the information concerning the 40-man unit may have been suspect, as it was sourced to a single other Guantanamo detainee named Mohammed Hashim, who was transferred back to Afghanistan in December 2009. Hashim alleged that this 40-man unit was responsible for assassinating key political figures and plotting to kill others. He also told authorities that the unit “provided security detail for” Osama bin Laden’s “convoy in Jalalabad, [Afghanistan] to enable his late 2001 escape from Afghanistan.” All of the reporting on this 40-man unit’s activities came from Hashim, who “is of an undetermined reliability and is considered only partially truthful,” according to JTF-GTMO. No other detainee corroborated his details.

JTF-GTMO thought that Ghani may have been maintaining contact with active Taliban members even as he was detained at Guantanamo. He “received multiple letters from an individual named Abdul Hadi Agha,” who revealed he had been in contact with other detainees in his writings. “Abdul Hadi Agha may be identifiable with an active Taliban insurgent leader and commander in Kandahar and Helmand provinces,” JTF-GTMO found.

During his combatant status review tribunal (CSRT) at Guantanamo, Ghani was highly confrontational, rejecting the tribunal’s authority. He said the tribunal members and the US were the real enemy combatants, as they were bombing Afghanistan. He also denied knowing anything about al Qaeda.

While he did not admit playing any role in the attacks against the Americans in Afghanistan, he did concede that he was a jihadist. “Do you believe in Jihad?” one tribunal member asked him. “Why not? I am a Muslim. We fought Jihad against the Russians.”

Shawali Khan (ISN 899) is “an admitted member of the Hezb-E-Islami Gulbuddin (HIG) with ties to the Anti-Coalition Militias (ACM), and possible ties to al Qaeda’s terrorist network and Iranian extremist elements.” Khan “conducted terrorist operations against US and Coalition forces” and has “familial ties to a high-level HIG leader who remains active against US and Coalition forces in Afghanistan,” JTF-GTMO found in its October 2008 threat assessment.

Khan was first recruited to fight by the HIG during the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan in the 1980s. JTF-GTMO cited some evidence suggesting that Khan briefly served the Taliban in the 1990s, and participated in fighting against the Northern Alliance.

By early 2002, Khan was allegedly part of a cell commanded by his uncle Zabit Jalil, who directed Khan to “place and detonate mines” outside a base near Kandahar. Jalil reportedly received his orders from Mullah Obaidallah, the former Taliban defense minister.

Khan was captured in late 2002 and a search of his home turned up numerous suspicious materials, including an al Qaeda “training manual covering topics such as surveillance, assassination, and interrogation techniques, which is similar to other al Qaeda training manuals found in Afghanistan.” Handwritten notes found in the manual mentioned “traditional and untraditional wars” including those using nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. Three books of poetry written by a high-ranking bin Laden confidante were also found in Khan’s home. However, Khan claimed that he was uneducated except for being able to read the Koran in Arabic, suggesting the manual and poems were not really his.

Jalil, Khan’s uncle, remained active in the insurgency long after Khan’s arrest. JTF-GTMO described Jalil as the co-leader of a joint HIG and Taliban force. Jalil and his colleague “had the responsibility of maintaining HIG and Taliban connections with the Iranian government.” Jalil and his comrade “requested weapons and other supplies from Iran in order to conduct” attacks against US and Coalition forces. JTF-GTMO found that Jalil’s cell received some of the support Iran agreed to provide to the insurgency. Jalil also allegedly maintained ties to Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency, working to free Taliban prisoners in Pakistan’s custody.

Jalil reportedly met with Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, a longtime al Qaeda and bin Laden ally, in May 2008. Hekmatyar allegedly provided Jalil with “a suitcase containing an unknown amount of US currency.”

During his combatant status review tribunal (CSRT) and administrative review board hearing, Khan denied any knowledge of the allegations levied against him and his uncle.