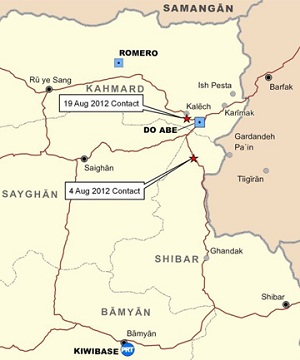

Afghan Insurgents are penetrating Bamyan province through the rugged regions of Shibar and Do Abe. Photo courtesy of the Nation. |

As NATO forces continue to scale down combat operations in Afghanistan, New Zealand forces that have been stationed in the relatively stable central province of Bamyan since 2003 have quietly and permanently closed two of their forward operating bases in the troubled Do Abe district. The bases were deemed crucial bulwarks in the fight against Taliban insurgents who have increasingly threatened the security and stability of one of Afghanistan’s most vulnerable regions, the Hazarajat of central Afghanistan — which encompasses the highlands of Bamyan and Daikundi provinces, large tracts of Wardak province, and smaller segments of Parwan, Ghazni, Ghor, Sar-i-Pul, and northern Helmand provinces.

New Zealand defense sources confirmed the base closures on Oct. 31, but the bases, including the crucial forward operation base (FOB) Romero in Do Abe district, were probably closed and dismantled in early October, according to Fairfax Media.

Following a series of deadly attacks against its forces in August, New Zealand announced it would prematurely withdraw its 145-man contingent from Afghanistan in April 2013. New Zealand had originally committed to keep its forces in Bamyan until September 2013. New Zealand suffered five fatalities in two separate security incidents in August, making it the bloodiest month for New Zealand forces in Afghanistan since they created the 145-man Provincial Reconstruction Team (PRT) in Bamyan in 2003.

On Aug. 4, Taliban forces led by Khwaja Abdullah counterattacked an Afghan security unit attempting to disrupt a Taliban IED cell in the Baghak area of Shibar district. Taliban gunmen then ambushed a 40-man ISAF unit comprised of New Zealand soldiers dispatched to support the besieged Afghan force, killing two New Zealand soldiers and four Afghan National Security Directorate (NDS) commandos. Six other NATO troops and 10 NDS personnel were wounded in the Aug. 4 attack. Afghan police officials speculated that 15 Taliban fighters were probably also killed in the skirmish, and two were arrested, including the brother of Khawaja Abdullah, both of whom were reportedly injured in the battle.

Bamyan in transition: no ANA, and ill-equipped police

Currently, there are no Afghan National Army (ANA) units garrisoned in Bamyan, and the 800-man Afghan police force in Bamyan is ill-equipped to counter attacks conducted by heavily armed Taliban insurgents. Local police have repeatedly complained that their small arms and unarmored vehicles are no match for insurgents armed with rocket-propelled grenades, heavy machine guns, mortars, and deadly roadside bombs.

“At the time of the hand-over ceremony, the transitional authority promised to increase the number of police, and give them better training and equipment, but these promises did not materialize,” Mohammad Akbari, a lawmaker from Bamyan, told the Los Angeles Times in August of this year. “There are no Afghan soldiers, and the number of police is not more than 1,000 for the entire province …. If there are no remedial measures, there are fears that security will get even worse.”

Even prior to the security incidents in August, Habiba Sarobi, then provincial governor of Bamyan, conceded that the Afghan police in Bamyan were ill-equipped to counter insurgent attacks. “The number of guns that our police have is not really sufficient,” Sarobi told the Guardian in July. “Our military needs some more supplies, some more support for training and equipment.”

On June 6, suspected Taliban gunmen laid siege to the residence of Haji Mohammad Mohaqiq, a prominent ethnic Hazara political leader and former mujahideen commander, in the provincial capital of Bamyan province. Mohaqiq serves as a Member of the Afghan Parliament and is the political leader of Hezb-e Wahdat (Islamic Unity Party). The brazen attack against one of the most prominent officials in Bamyan is symptomatic of a beleaguered police force and an overall security failure stemming from the rise of insurgent sanctuaries in nearby Parwan and Baghlan provinces. Most noticeably, there is growing insecurity along two vital highways connecting Bamyan with Kabul.

Road insecurity severing the Bamyan-Kabul corridor

The most unstable areas of Bamyan include its northern and eastern districts of Shibar and Do Abe. There are two main roadways linking Bamyan with Kabul: the Ghandak highway, which cuts through Shibar district (the Shibar Pass) and into the Ghorband Valley of neighboring Parwan province; and the southern route, which crosses the Hajigak Pass into Wardak province — itself a hotbed of militant activity.

Although New Zealand lost a soldier and suffered three casualties in an IED attack in the area in August 2010, trouble emanating from Do Abe and the corridor between Bamyan and Parwan became more evident in June 2011, when the popular Bamyan Provincial Council Chairman, Jawad Zahak, was kidnapped and beheaded by Taliban militants manning a checkpoint in the Ghorband area of Parwan province. The Ghorband Valley, which stretches through four of Parwan’s 10 districts, is mostly under Taliban control, according to a recent report in the Global Post.

Between July and August of this year, 26 civilians from Bamyan were killed in Wardak province, six more were killed in the Ghorband valley of Parwan province, and six soldiers were killed on the Baghlan highway, according to a local resident who spoke with Pajhwok Afghan News. In mid-October, a convoy belonging to Afghan Second Vice-President Karim Khalili was ambushed by heavily armed insurgents in Parwan as it traveled to Bamyan; reports conflicted as to whether there were casualties among Khalili’s guards.

The increasing danger associated with traversing the once-dependable road system linking Bamyan with Kabul has prompted provincial officials to demand additional resources from the Karzai regime for safer modes of transportation.

“We have asked the central government to provide us with helicopters,” Ahmad Alia, a spokesman for the Bamyan police chief explained to the New York Times in late October. “Local government officials are not traveling by ground anymore, and they want to have helicopters so they can go to Kabul or other provinces.”

Hazarajat region increasingly vulnerable

The consolidation of New Zealand’s forces to the main NATO base in Bamyan, known as Kiwi Base, was timed to curtail having to maintain FOB Romero in hostile territory through the upcoming winter. Weather and climatic conditions in central Afghanistan typically present a greater threat to provincial security than do insurgents, as heavy snowfall makes roadways impassable, sometimes for several months. However, the withdrawal of NATO forces from Bamyan by April 2013 will leave an ill-equipped police force to fend off heavily armed insurgents from encroaching on Bamyan from the unstable and insurgent-dominated districts of neighboring Baghlan and Parwan provinces.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Kabul intends to provide Bamyan with a quick-reaction company before the spring, and expects to increase the size of the local police force later next year. But little else has been offered — no mentions of, or promises for, heavier firepower, armored vehicles, increased intelligence capabilities, or the commitment of aerial assets.

The vulnerable Hazarajat region — home to nearly 5 million people, most of whom belong to the ethnic Hazara minority — could once again become one of Afghanistan’s most ferociously contested pieces of territory following the NATO withdrawal in 2014.

2 Comments

No offense to the New Zealand troops themselves, but in the eyes of their politicians, when the going gets tough, NZ gets going.

On the other hand, perhaps they are seeing the lost cause named Afghanistan whose only hope lies in the Tajik/Uzbek militias rearming and a redux of the 90’s war.

According to The Asia Foundation, Hazarajat is the place to be in Afghanistan – the most content, most liberal part of the country:

http://afghansurvey.asiafoundation.org/is-afghanistan-headed-in-the-right-direction#2012

Funny enough !